In her essay, Mulvey focuses largely on Hithcock's Rear Window, and understandably so. Rear Window is so involved with the idea of the gaze, that it is essentially a film about the gaze. Mulvey argues that female main character, Lisa Fremont, is constantly asked to be looked at through Hitchcocks close-ups and choice of costumes. While this may be true, for she is often shown in flattering soft light, what is more interesting about Rear Window and Mulvey’s discussion of it is the voyeuristic gaze of Jefferies. In the film, Jefferies is confined to his wheelchair, due to a broken leg acquired from some dangerous photography assignment, and in order to relieve his boredom, he begins to watch his neighbors through his window. Ultimately, Jefferies is given a voyeuristic power that aids in the arresting of a murderer. One of the most powerful tools used by Hitchcock is subjective camerawork. In order for us to understand that Jefferies is the one viewing, Hitchcock first gives us a shot like this:

Followed by a shot of what Jeffries is looking at, like this:

Because of shots like this, the viewer is placed into Jeffries' subjective perception, which in turn would technically allow us to see Lisa like Jeffries does, which becomes problematic. While Hitchcock does put Lisa on display, Jeffries is not interested at the beginning of the film, and if we are situated in his perception, then we should not want to see her as an object of desire. The solution to this problem can be found in the theory of fantasy and desire, which I discuss in depth on the other theories page.

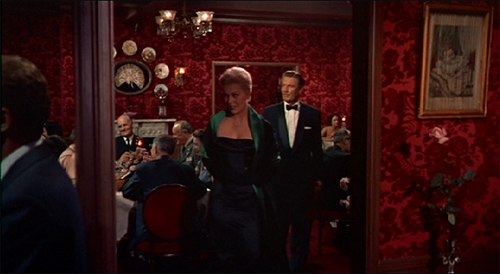

In Vertigo,, Hitchcock practically begs you to look at the female lead as an object of beauty. In the first scene that we see Madeline, we first see Scottie looking out into the restaurant, followed by a shot of Madeline and Gavin walking towards Scottie, to exit the restaurant. Again, we have an example of Hitchcock's subjective camerawork, so that we are placed into Scottie’s perspective viewing Madeline. As the two are walking, the light on them is fairly even, the background is well lit.

A few frames later, the dining room grows dim, Gavin is in shadows, but Madeline is bathed in light, her white skin standing out against her dark green dress.

As she walks into the bar, the light on her becomes brighter and the camera pulls in tighter onto her face. With the use of lighting and costuming, Hitchcock brings your eye to Madeline, as Scottie's eye is drawn to her as well. While this may not necessarily suggest power in looking, Madeline is a passive object. We are supposed to view her as Scottie views her, as something beautiful and unkown, an idea that Mulvey relies on.

What is also interesting about Vertigo in conjunction with Mulvey's idea about the gaze is that Scottie's character becomes so obsessed with Madeline. When he meets Judy, he instantly sees Madeline in her. Throughout the rest of the film, he is obsessed with the image of Madeline and having Judy look like her. Obviously, his gaze is powerful, so controlled that he can alter the image and make it fit his fetishistic desires.

Hitchcock uses Mulvey's ideas about the gaze in a variety of ways, though strongest through subjective camerawork. This device places the audience with a certain character, giving the audience viewing power. Still, Hitchcock likes to complicate things a bit by not always aligning point of view and identification.