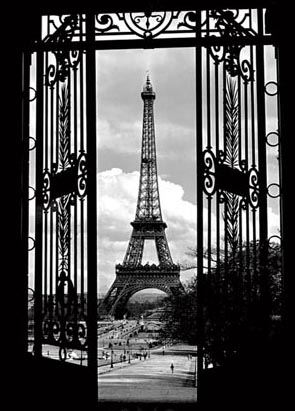

Though originally designed as the entrance to Paris' 1889 Exposition Universelle, the Tower has since traveled across physical and metaphorical boundaries to become a sign in locations quite distant from its Parisian home. This simple architectural design is now recognized globally as a synecdochal sign, or "a part of something standing in for a whole," of Paris itself (Rose 87). Thus, it operates as such even when removed from its conventional environment. Because of its presence in popular culture and on the lifetime to-do list of tourists, millions of people flock to the French capital every year just to take pictures of this monument and travel to its summit.

However, Davydd J. Greenwood argues this is no longer the most popular way of experiencing the world's most historical locations:

"Tourists who seek out historical sites and monuments and who revel in their awe over the past are but a small portion of the total array of tourists. A much greater magnitude of economic activity is generated by resort and theme-park tourism carried out in entirely new and purposefully artificial environments. We know intuitively that such modern tourist sites are different from the ruins of Rome, but how and why and to what end do we make distinctions" (Lasansky and McLaren xix)?Despite the original Eiffel Tower's ability to attract tourists, replications found at the Paris Las Vegas hotel and at Disney's Epcot exude enough Parisianness, or even general Frenchness, to satisfy those who never travel to the actual monument. Referencing Rob Shields, David Crouch and Nina Lubbren claim this could be because of place-myths:

"Place-myths are conglomerates of place-images, that is, stereotypes and clichés associated with particular locations, in circulation within a society. Place-myths need not necessarily be faithful to the actual realities of a site; they derive their durability, spread and impact from repetition and widespread dissemination" (Crouch and Lubbren 5).It is likely the Eiffel Tower's reproductions are place-images contributing to a constructed Paris or France place-myth within environments such as Las Vegas and Orlando.

With the popularity of such replicas, we also "might be seeing the triumph of the kind of overseas tourism American tourists to France have often wished for: foreign tourism without foreigners" (Levenstein 288). Although this is a probable reason for the construction of such copies, it cannot completely explain the draw of consuming simulations over the actual Eiffel Tower. Basically, there is a choice to experience one in place of the other which is not easily explained. Jean Baudrillard, as discussed by Gillian Rose, would say this occurs because of "the simulacrum" (Rose 4). In other words, "it is no longer possible to make a distinction between the real and the unreal...we now live in a scopic regime dominated by simulations, or simulacra" (Rose 4). If Baudrillard is correct in explaining this gray area of society, is the existence of the simulacrum progressive or problematic? To address this concern, I return to the questions posed by Greenwood above: if we know that reproductions differ from the original, is it possible to distinguish between them, and do these distinctions matter?

With these questions in mind, I briefly explore

the history of the Eiffel Tower sites at Paris, Las Vegas, and Orlando. After explaining how each

came into being, I look at the Eiffel Tower's power as a synecdochal sign for Paris, and consequently

for France, within and outside of each location. Then, I examine distinctions between the particular

Tower discussed and the others. Finally, I discuss the difficulty of recontextualizing the Eiffel

Tower as a visual object, because of its consistency in meaning. I assume the concept of place-myths

and the simulacrum are already at work, and therefore choose instead to study Vegas and Epcot as

institutional apparatuses using the Eiffel Tower as an institutional technology. By institutional

apparatus, I refer to the "forms of power/knowledge that constitute institutions" (Rose 174).

In other words, both of these locations are designed to discipline visitors according to their

individual ideologies: what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas, and Disney makes dreams come true.

Furthermore, they create environments capable of using the Eiffel Tower to signify Paris, or France

in general. As an institutional technology, the Eiffel Tower becomes one of the "practical techniques

used to practise that power/knowledge" (Rose 175).

From my perspective, Paris is an innocent bystander

in the Eiffel Tower's perpetual movement across space and time. This does not mean the city overlooks

capitalizing on the Tower's popularity. On this point, I agree with Daniel Jewesbury's opinion: "The

commodification of the tourist site involves an ideological as well as a financial investment.

Returns on one are dependent on the flourishing of the other" (Jewesbury 228). Though there are many

Parisians who take advantage of the Eiffel Tower's strong image by selling thousands of miniature

models, posters, and t-shirts, this would not be possible if it did not hold ideological power in the

first place. Additionally, in my view these souvenir salespeople are not mini-institutions at work

using the Eiffel Tower as a technology. Instead, they are business-minded individuals in need of

employment and accessing their available resources. Also, they do not discipline or construct

consumers of the Eiffel Tower in a certain way, automatically eliminating the possibility of this

group as a collective institutional apparatus.

Please feel free to enjoy each realm of this site

both in its own context, and when supplemented by your preexisting knowledge. Eiffel Tower fanatics,

or viewers who have comments and questions, can contact the author by e-mail

here.

Paris, Las Vegas, or Orlando?

a class taught by Bob Bednar in the Communication Studies Department at Southwestern University