Margaret Duffy's work in studying women and how they consume advertising, understand it and find themselves in advertising argues that "advertising is a bellwether of cultural trends" (5). Advertising itself is a "mirror of social values, and a powerful, usually malevolent force that shapes those values" (Duffy 5). Mac cosmetics teamed up with Mattel and the Barbie brand to create a line of makeup that mirrors the painted face of a Barbie doll. Models donning the cosmetics of a doll, pose in the advertisement for Mac's new line. The women in the photograph display typically Barbie-like traits. One has bright blonde hair and rounded eyes, drooping her vibrant pink lips. The second woman is dark-skinned with black hair, sparkling green eye shadow and the same doll-like lips. Both models wear pink. Both are looking out and away from the camera, diverting their gaze upward. Each Barbie-like model is asking to be looked at. She is allowing viewers to see her face, her eyes and lips as frozen and still paintings. Their blank stares call upon the emptiness of the actual doll's facial expression. The mortise in the upper right corner of the image reminds readers that the cosmetics, while eliciting a Barbie-feel, is actually endorsed by the Barbie brand and manufactured to purposefully look like doll-make-up. The construction of Barbie as a cultural icon "involves a dense web of products identified not only with Barbie and Mattel but also with other corporate sponsors and popular culture" (Rogers 95). Mac and Mattel make an agreement to sell, promote and distribute the image and ideals of Barbie though a joining of companies. Each benefactor profits. Mac sells makeup and Mattel promotes an image and ideal of Barbie-Beauty through product purchasing. Mary Rogers' exploration of Barbie as a commodity in Barbie Culture expands on the doll's iconography:

Much of Barbie's iconic status has built up from these countless connections with other commodities characteristic of postindustrial economies. Such commodities speak to desires shaped by mass advertising and fulfilled along the border between fantasy and reality... Barbie could scarcely sustain such like without massive advertising and innovative retailing (95).

Barbie's iconography is very much a result of cross-product placement. The Mac/Barbie team produced an advertisement that calls on Barbie enthusiasts and makeup lovers alike. The appellation in this ad calls to consumers to purchase this line of makeup in order to look like Barbie, be like Barbie. "Hey you!" it says, "If you think Barbie is pretty and you want to be pretty, then buy this makeup and you will be!"

The advertising strategies in the Pink Fiat print ad feature a wealth of intersecting ideologies. As advertisements shift from "merely announcing the availability of goods and merchandise to attempting to define wants and needs" the content, proposition and communicative tools change as well. (Budgeon 55). The Pink Fiat ad tells a story of a particular life style availed to the woman seen in the image. By buying the car, women are buying all of the stereotypes, ideologies and images that go along with Barbie herself. "Barbie is no abject icon of oppressed womanhood" Rogers proclaims, "Instead she takes the signs of women's subordination… and turns it into the stuff of success, fun excitement, and glamorous. Barbie is a creature of privilege" (Rogers 36). Barbie's Pink Fiat embodies just that… privilege. For a woman to see herself in the ad means that she is holding her own image along side the image of Barbie. Exhibiting a seemingly unachievable perfection, the human-Barbie in this ad calls on real women to participate in similar ways of dress and grooming in order to achieve greater Barbie-ness.

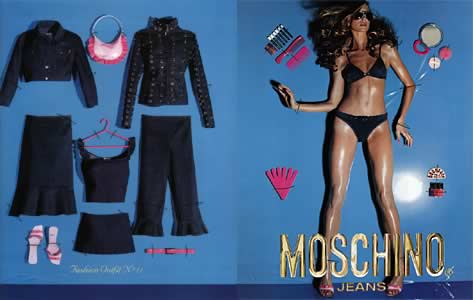

In working to look more like Barbie, more like a man-made image of beauty, these ads suggest human women should exhibit Barbie-like features. "Women striving to achieve the answers to the beauty mythology, often find that the image that they have known as familiar and perceived as beautiful, is the reproduction of a doll recognizable to all" (Weissman 40). In this ad Barbie is a real women. She is strapped to the box just as a doll would be and is surrounded by her accessories just as a Barbie is sold. The only difference is that this ad is selling human clothing. The Barbie box suggests that these are items Barbie is sold with thus they must be vital and important components of her personality and being. The Moschino ad asks women to see themselves in the same way. If a doll cannot function without her accessories neatly tied into her box, then real women will not be able to live without their products. An inventive way to sell clothing moves into a social commentary on the idealizing of a doll. "Doll and woman symbolize one another. Not only does a fashion doll like Barbie symbolize a culture's idealized Woman but also women commonly make themselves into real-life versions of the idealized image the doll represents. The artifact thus points to the idealized body, and bodies struggling to become ideal point back to the artifact" (Rogers 115). Consumers on a quest to reach the perfect standard of a doll, use their values to help determine the importance of goods and services that bring them to the expected level of acceptance. The people who internalize these ads and purchase the products because of them "identifies with a cultural image or iconic presence in society, and is described as being aesthetically oriented. Therefore, those that desire the Barbie image are people who seek out and focus on the connection of their perceptions and experiences" (Weissman 39).

|

|

|

|

|

|