|

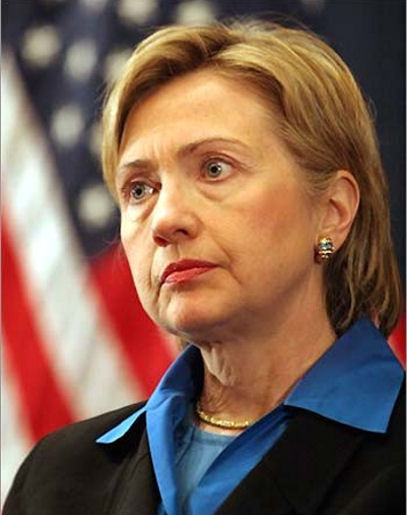

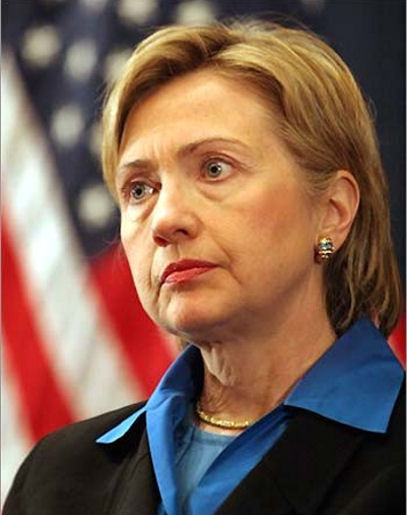

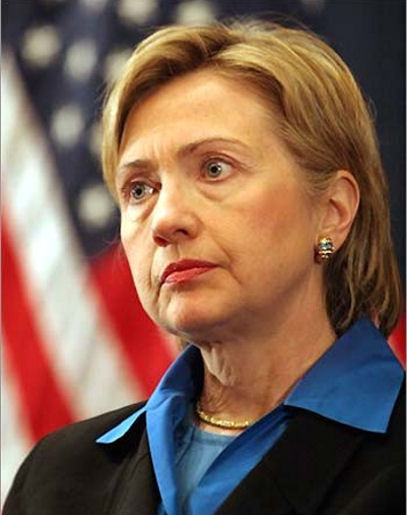

Since its earliest beginnings, politics in the United States has been long dominated by men. Politics has historically excluded women, as gender norms socialized women to be passive, doting, and accepting, rather than confrontational, savvy, and aggressive, as men are socialized to act. These socialized gender constructions had long oppressed women, and restricted them to the home and domestic sphere, where they were expected to care for the house, yet have no final say in what happened within it. Women were not seen as needed within the public workforce until World War II occurred, and caused a shortage of men in the United States due to the draft. Women were then expected to silently and willingly leave their homes to go fill these job gaps, and then gladly leave these positions when the war ended so the men would have their jobs waiting for them again when they returned home. Women were not seen as fitting for any other work besides domestic labor, and for decades, were much less seen as capable of making the best decisions for themselves, or having a voice and claim to politics at all. It was not until after long years of women battling for their suffrage that they were granted the right to vote and run for office through the nineteenth amendment, in 1920. This was fifty years after the fifteenth amendment made it illegal to deny a citizen, in this case man, the right to vote based on their race, color, or status (slavery). Even heading into a new millennium, women were still scarcely represented in politics, and with the 2008 presidential race, femininity and politics became a major factor that weighed on American citizens' minds. With Sarah Palin on the Republican end of the presidential race and Hillary Clinton on the Democrat side, the media has had a field day comparing a veteran politician to an up and coming woman with different ideals, politics, and a different look -- which became an interesting factor in public opinion, as "mass media play a role in structuring our understanding of reality and helping us make sense of the world" (Harp, Loke, and Bachmann, 295).

|