"Elevators (and stairs, for the athletic) lead to the three platforms open to the public. The highest platform houses the restored private apartments of Gustave Eiffel. The tower also has a brasserie, restaurants, and an audiovisual museum explaining its history" (Bialtestowski and Lefèvre 50).Seemingly, the Eiffel Tower contributes to the French economy more than the French identity.

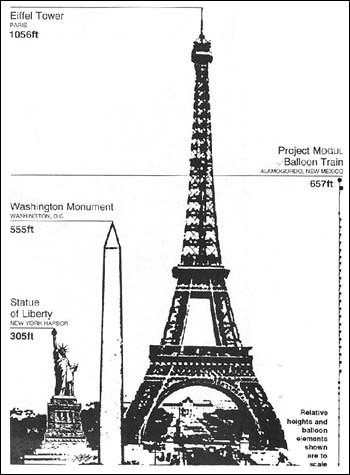

The original differs from its duplications in size and location. While Gustave Eiffel's creation

is 1,063 feet tall, "weighs 7,000 tons and contains 15,000 components connected by 2.5 million rivets,"

the Vegas version is only a half size replication (Bialtestowski and Lefèvre 50). However,

Eiffel's "original drawings were constructed" to construct the Paris Las Vegas replication

(Benson 57). Even smaller and less accurate is the Epcot version, which is approximately a one-tenth

version of the real Tower. Also, the Vegas and Epcot replicas exist in environments meant to be full

of entertainment, while the real Eiffel's surroundings are full of French history.

"The Champs-de-Mars, a former military parade ground and setting for Paris' World Fairs, is a carpet

of green running from the tower's base to the Ecole Royale Militaire, founded by Louis XV in 1751"

(Bialtestowski and Lefèvre 50).

Regardless of where it is, the Eiffel Tower

is a forever a symbolic sign for Paris, and therefore France. "Symbolic signs have a conventionalized

but clearly arbitrary relationship between signifier and signified," meaning symbols often come to

stand for what they signify (Rose 83). To outsiders, the Eiffel Tower means Paris. Shields'

idea of place-myths can be applied here, because the Eiffel Tower image alone can "conjure up an

entire site, region and structure of experience by representing only a fragment"

(Crouch and Lubbren 5). There is much more to Paris than this single monument. However,

it is very difficult to detach this association. That is, of course, unless you are Parisian,

in which case the Tower is simply a convenient and useful communication device.

Therefore, the Eiffel Tower's power as a sign depends on the regime of truth held by its viewer.

By regime of truth, I mean "the particular grounds on which truth is claimed" (Rose 144). In the

eyes of Parisian citizens, it is a postmodern tool. If its antennas or lights fell off, the Tower's

signifiance to Parisians would diminish. Conversely, for outsiders it is a French monument signifying

Paris, and will remain so whether useful or obsolete. Thus, there is "complexity and contradiction"

within the initial Tower's reputation as a sign (Rose 164). The reason for its importance is dependent

upon its viewer, but without both types of viewers, its modern day status is incomplete. Parisians

need it, and the rest of the world wants it. Even if its duplications are more popular for tourists,

the Tower's presence as a symbol in our worldwide visual image bank is important.

Because the Eiffel Tower is unendingly used as a sign for Paris, and is widely recognized as such,

there is nothing else for which it could possibly stand. Even outside of its home in the French

capital, the Eiffel Tower continues to stand for Paris and France. Because of this, it is not easily

recontextualized. Gillian Rose argues recontextualization occurs when "an object passes through

different cultural contexts which may modify or even transform what it means" (Rose 223). However

this image, or object, in particular can exist in any location and maintain the same meaning.

Whether it is in France, Nevada, Florida, or a lamp on someone's desk, the Eiffel Tower equals

the city of Paris, and the county of France. Because of the ability to easily recognize this

monument's physical structure, its simulacra are able to metaphorically stand in for the authentic

creation.