| The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century was the beginning of the employment of anti-catholic sentiment where "the cross was 'not a symbol of redemption through the blessed Saviour, but a perverted, abused symbol of a great system of superstition and imposture.' The use of this symbol on Protestant churches not only tempted 'idolatry,' but it also confused religious loyalties." This harsh reaction expressed by Smith is not an overstatement or exaggeration, and it was not until the mid 1800s that the cross was deemed an acceptable expression of faith in the Protestant church when churches began to recognize the "appeal based on [Catholicism's] recognizable heritage and their promise of sensual access to sacred mysteries" (Smith 711). But even in this renewed acceptance of the cross, "the crucified Christ, especially in life size, [...] was generally perceived as unnecessarily morbid and graphic by Americans; the preference was always for the un-embodied symbol of the cross over the crucifix" (Promey 111-2).

|

|

|

|

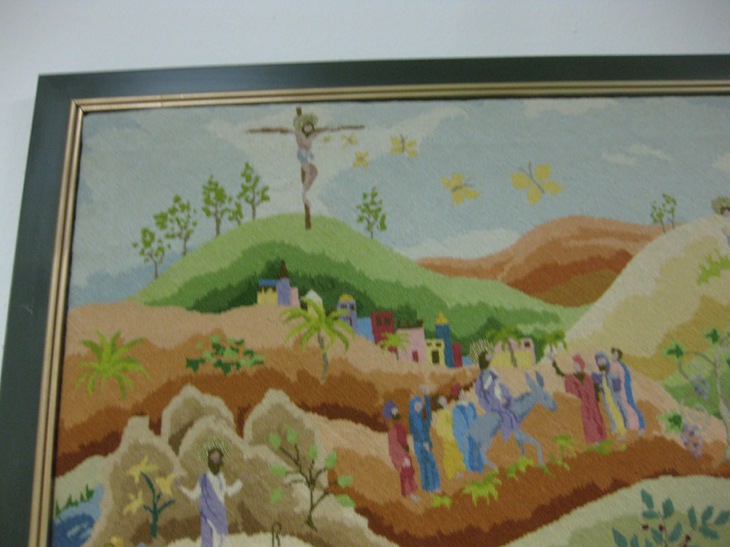

In the Protestant church, the rhetoric of the crucifixion was established through hymns, prayers, sermons and the independent study of scripture. As a part of the Reformation, "the English produced a significant literature and molded theology totally by language, at the same time narrowing the horizons of visual perception. Seeing was not a mode of learning to be trusted in its own right" (Dillenberger 15). This theme was overwhelmingly communicated in my discourse analysis of imagery. The only Protestant imagery found of the crucifixion was in books or within the context of a visual narrative of Jesus' life, death and resurrection. Visuals of books were much more common in sanctuary stained-glass windows. For example, the Lois Perkins Chapel at Southwestern University displays eleven aisle stained-glass windows displaying fathers of the Protestantism and Methodism. Their commonality is not a cross, crucifix or a triune symbol, but rather a book, communicating that it is through education and learning that knowledge, understanding and clarity of suffering, pain and doubt are dealt with and resolved.

|

| This is the antithesis of the approach to direct visual representation of the body of Christ in the Catholic Church. Upon entering every Catholic sanctuary I visited, the first and most striking image was a larger than life, usually freestanding, representation of Jesus hanging on the cross. The physical semiotics of these representations are meant to demand an overwhelming reaction from the viewer, though these readings differ from person to person based on "the appearance of the object, the words they [have] heard, the texts they [have] read, the lives they [have] led" (Lipton 1173). In a preliminary reading of the crucifix, after morphing the signifiers into signifieds, the viewer could conclude that a man, Jesus, is nailed to a cross with a crown of thorns placed on his head, clothed in a modified loincloth. The denotative understanding of his position, "one analogous to literal exegesis of Scripture, would say that the head leans because Jesus is dead or dying, that the arms are extended because they are nailed to the cross" (Lipton 1173). This meaning can hardly be disputed, but a 'second-order semiological' meaning, as classified by Barthes, of what Jesus' physical placement on the cross is what becomes complex (Rose 131). Sacred imagery, more than commercial/popular imagery, requires the viewer to "enter into a relation with the image in which they are expected to participate imaginatively, contributing what the image itself may not provide but must presuppose if it is to touch the viewer" (Morgan 75). Rose echoes this in her emphasis on the expectation that viewers will "depend on codes held by the particular group of consumers their markets want to sell their product to" (128). And although religion is not a commercial industry, the Catholic Church does follow a specific theology and doctrine that serves as a presupposed base, which is common to all viewers. It is through deeper meditation on and enacting given/expected understandings of the context of the image that one may "see in Christ's posture a nod and an embrace" and a "suffering but paradoxically powerful body" (Lipton 1175, Verdi 104). Individual readings allow "the very ugliness of the Passion" to be read conversely as a "spiritual force" that reveals "the glorious Christ that Christians seek" (Lipton 1186, 1185).

|

|