|

My senior year of high school one of my best friends was Catholic and for my birthday she gave me a rose scented rosary. Although I am not Catholic, that object, displaying the crucified body of Jesus Christ, still has spiritual significance to me, because it reminds me that through personal relationships and love for your neighbor, we create a stronger relationship with Christ. While mine is not the dominant code for this object, (which is rather to use the object in order to tangibly exercise prayers of atonement to Mary, Queen of Heaven) I still possess a unique relationship with the object that allows me to make certain and specific readings and meanings from it. Now looking at this object as a visual object I also see it as a tool for disciplining my spiritual life, whether I use it for its intended purpose or not.

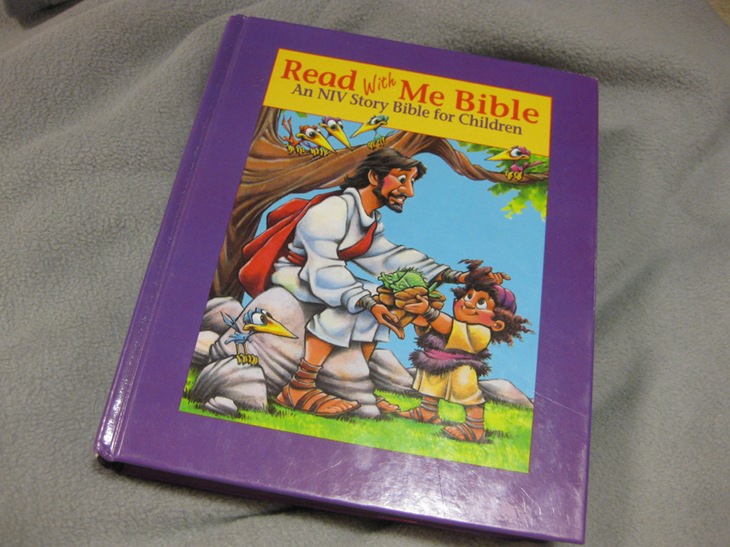

Similarly, I also possess a relationship with a certain children's Bible. This Bible was a gift to me from my church as I entered the first grade. I had primary literacy skills, but still relied on illustrations and my parents' help for comprehension. As I now analyze this book as a visual object I am first faced with understanding of the significance of how this book ended up with me, in my house, as a six year old. Appadurai articulates, "Even though from a theoretical point of view human actors encode things with significance, from a methodological point of view it is the things-in-motion that illuminate their human and social context" (qtd. in Rose 288). |

|

|

|

In viewing my rosary as a "thing-in-motion" there are several signs that place its meaning within my social context. First, the unique interconnectedness of the ability to touch and to smell the object creates a connection with my senses, which is unique to this object. Seltzer also identifies that, "tactile memory evoked in the use of the rosary's "helping recall other times of prayer.' Further, 'the fingers' transit along the beads [...] can help put one in a prayerful mood'" (9). Being able to hold the rosary in my hands, understanding the iconigraphical significance of the object within the Catholic faith, results in my own adjustment into an attitude of reflection. And although I am not Catholic, I feel somehow incorporated into that community and doctrine due to our common general reverence for the object as a spiritual guide. McDannell describes this as the importance and strength of an objects community affiliation: "When objects function as symbols of community affiliation, they do so in a fairly direct way. Their power can at times convert the religious objects from a reminder of communal solidarity into a focal point of religious contestation" (48). An example of this contestation might be the removal of all religious imagery by Protestants during the Reformation. The symbol and use of the rosary moved from serving as a "promise of sensual access to sacred mysteries" to "a piece of visual shorthand representing the sensual tools of Catholicism and the oppressive authority of the Catholic Church" (Smith 711,709).

While I have a small sense of communal affiliation with my rosary, the connection with my Bible given to me by my church, by people I directly know, is much stronger. The book has become a symbol of my community's affirmation of my faith journey and spiritual growth. After receiving the book from my church, this bible came on and off the bookshelf in my room as I read it, or my parents read it to me each night. As a bedtime story, this book became more than an exploration of faith, but a soothing assurance that I had nothing to be afraid of through the night. Softened images of the crucifixion followed by exaggerated, pure, bright, surreal and superhuman depictions of the resurrection assured me that as long as I believed in the Jesus I saw in the picture (ascending like a superhero with muscular arms and a puffed out chest, ready to challenge anything that came in his way), he would fight the boogie monsters in my closet and fend of the bad dreams that might come my way. Both the rosary and the book are symbols and objects of personal faith contemplation and growth. These personal manifestations of religious devotion symbolize "the private, hidden, intimate dimensions of a religious faith" that are significant to the individual, though they are completely (and subtly) dictated by what the institution allows the participant to do with the object (McDannell 46). With the rosary, the specific intent is to be used as a prescribed guide through prayer, and the book is laid out to linearly dictate a specific scriptural understanding that is to be learned from one's very first interaction with faith has a child. |

| Religious objects purposefully create this dual sense of belonging to a group, while simultaneously maintaining an individual relationship with the user based on personal lived experiences with the object. Much like the unity one feels knowing that millions of Catholics around the world pray the rosary, iconographic devotional candles produce both individual and group relationships between the object and the user. In every grocery store throughout South Texas and beyond, there is a section in one of the aisles dedicated to devotional candles displaying Jesus Christ, saints, and the Virgin Mary. As one looks at the candles on the shelf, they are visually presented with the fact that hundreds of others currently have or will purchase and use a candle just like it. At the "Chapel of Miracles" dozens of these iconic devotional candles are displayed, each one brought from an individual with distinct lived experiences and a distinct relationship with the candle and the image on it, but together they create a symbol of homage and reverence to the suffering Christ as they sit at the foot of the cross.

All three of these visual objects analyzed include multiple facets to their classification as a visual object that can be "seen, watched, touched, carried, and decorated," rather than simply a visual with only one avenue for interaction (Rose 283). The rose scented rosary appeals to both the senses of touch and smell, and it is through the tactile nature of the object that the participant is guided through the prayer cycle. The children's Bible also demonstrates this invitation into a physical and emotional relationship with the object through its size. As a first grader, the bulky, heavy and thick material form of this book communicated the importance and validity of the text inside. Held by small hands, the visual substantiality of the book put it in the same category as a reference book, such as a dictionary or encyclopedia; books that were not to be interpreted, but to be taken as fact. Although the depth of the book was considerable, the height and width of the book was proportional to my small frame, a visible sign that this book was for me to feel, touch, read and learn from. The votive candle also leads the viewer to this level of participation due to its changing form of lighted to dark. The way the light illuminates the image of Jesus on the cross through the glass gives the meaning that even through the darkness of suffering there is light coming through the hope of the resurrection. The mobility of the candle can also communicate different meanings to the participant. Devotional candles serve as a center for individual prayer, be a part of a vigil at the foot of a crucifix, or serve as a symbol of remembrance at the grave of a loved one. Rose identifies an "anthropological approach to images suggests that tracking objects as they move is a particularly fruitful way of accessing their significance" (288). Discovering the movement of a candle off the shelf at an HEB and into one's home where it becomes a part of individual devotion then on to sit at the base of a loved one's headstone dictates that meaning of the object as a form of intercession between the faithful and the holy. |

|

| By drawing meaning from the mobility, visual, material and presentational forms, as well as the intercalibration into a person's life, the significance of tangible religious objects can be identified and analyzed. Through the example of the rosary, children's Bible, and devotional candle it is evident that through mobile objects that "draw their viewers into a space of contemplation and discovery," religiosity is able to be an integrated part of life both in and outside church walls (Worley 42). |

| Identity in Icons |

|

Be Like Christ |