|

Images as Artifacts |

|

|

Images as Artifacts |

|

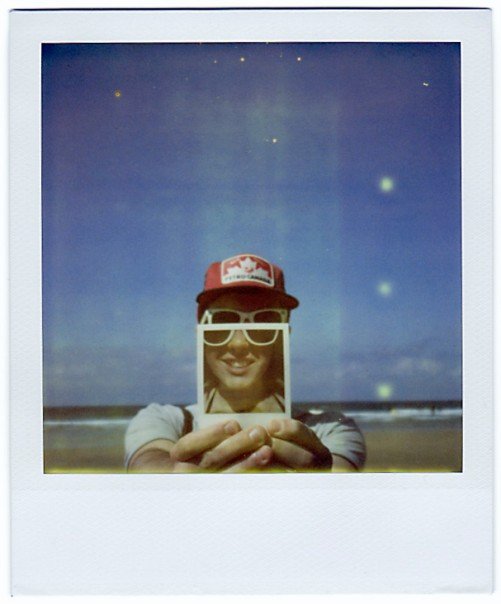

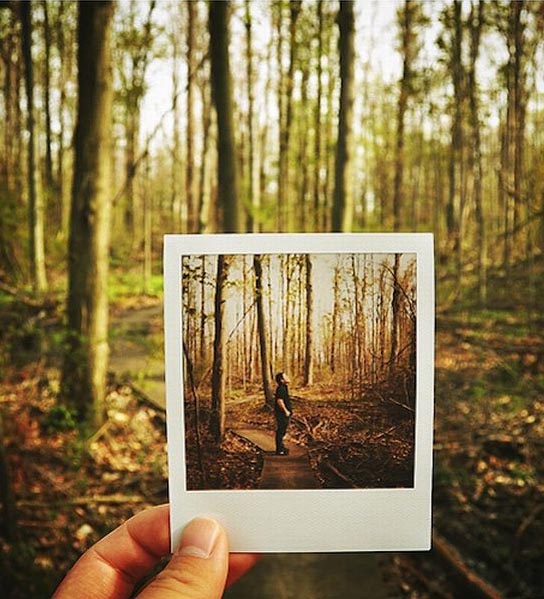

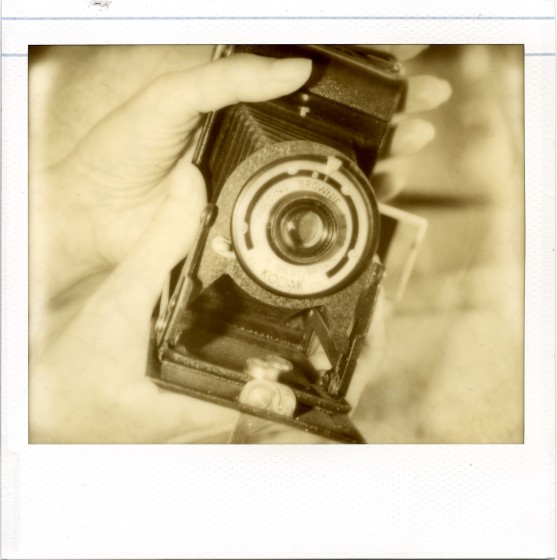

The anthropological approach to understanding visual objects relies on three main components: materiality, materialization, and mobility. Materiality encompasses the look and feel of visual objects, "their shape and volume, weight and texture" (Rose 219). And, while an image may have a range of physical and material qualities, materialization requires an understanding of how the image/object functions in the world, because "it is only when someone uses the image in some way that any of those qualities become activated, as it were, and significant" (Rose 220). Mobility, the last facet in the anthropological approach, is concerned with how objects travel over the course of time. "When things travel, the meanings and values that attach to objects becomes...evident" (Rose 223). "Barthes's notion of photographic reference revolves less around an image's visible content than around how photographs, precisely by disrupting temporal continuity, interconnect different instances of presence, refocus our sense of finitude, and thereby draw our awareness to the many ghosts that populate our own present" (qtd. in Koepnick 100).

|

|

|

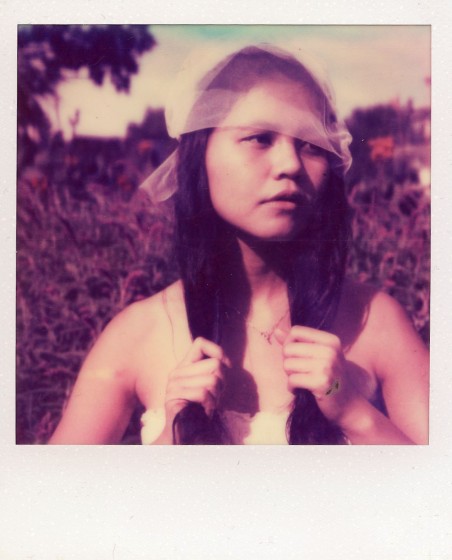

These qualities greatly affect how viewers and audiences interact with visual objects. Print photographs, for example, are objects that appeal to individuals' sense of touch for a number of reasons. They usually fit in the palm of a hand, and their tactile qualities seem to encourage the viewer to hold or touch them. Paying attention to these specific physical qualities helps illustrate how these images go on to be rooted in particular geographical locations, as well as within particular social and cultural contexts. Samantha Warren expands on these ideas about materiality and photographs by talking about how the unique materiality of photographs reminds us that they are not the object or subject photographed, they are an artistic interpretation of what the subject saw and felt, composed of chemicals, paper, and light (233). These tactile, physical qualities call upon viewers to engage with multiple senses besides their vision such as smell and touch. This sensory arousal allows for a deeper connection with the image and material form. The viewer is invited to meditate on the ephemeral nature of the tangible artifact.

|

|

|

Photographs, even though they are inanimate objects, have agency because they capture and suspend time, they preserve "reality" (Latour qtd. in Miller 12). Yet, "there is nothing permanent about the photograph. Whether in the silent sulfiding of silver emulsions or the fiery explosion of nitrate film, each image from the past carries within itself seeds of its own destruction" (Keefe & Inch 1). This liminal state between tangible representation and temporal performance is imperative to the understanding of why so many individuals still crave the option of instant photographic technologies.

History |