| While the similarities seem to stack up and say a lot about the visualizing of masculinity, the several differences between Maxim and GQ say a lot about the magazines' defining ideologies. The three differing subjects found in the magazines are fashion, women, and sex. While untrue about all editions of Maxim, this particular one had no articles or mention of fashion (besides a small list of golf supplies one needed, including shoes and a pair of pants). In fact, there was not even a single advertisement for shoes or clothing. The same could not be said for GQ. One does not place "look sharp" as part of their motto without being able to supply advertisements, articles, and everything in between regarding fashion. Suits, shoes, ties, and pocket squares all get incorporated within this edition, letting the reader know exactly what to wear, and how to wear it. So what does the stark difference between the two magazines' mean in terms of visualizing masculinity? As far as Maxim is concerned, smelling nice is all a man needs in order to present himself as masculine. GQ, begs to differ, stating that being masculine means being able to look sharp on top of keeping up with personal hygiene. GQ places emphasis on fashion as one of the key factors of being masculine. Maxim, on the other hand, puts its emphasis on women and sex.

|

|

|

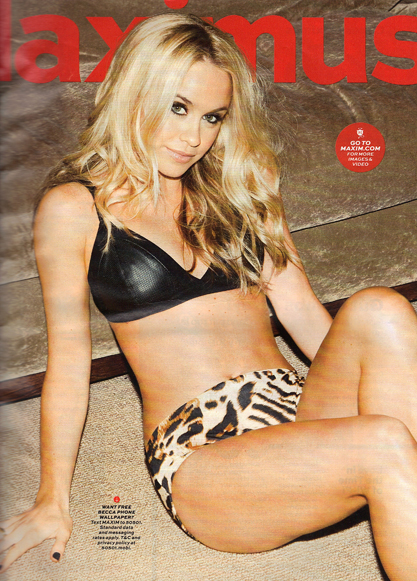

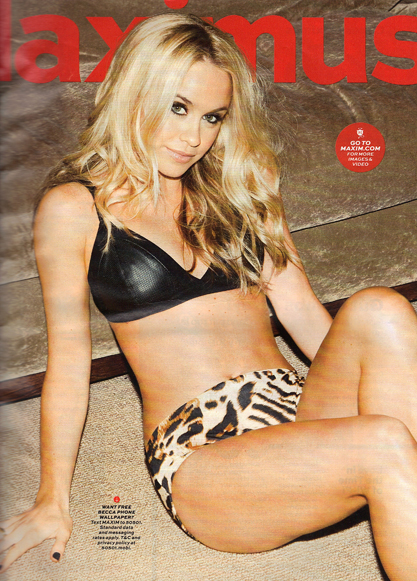

Women and sex almost always get depicted as going hand in hand within Maxim. In their article discussing hyper-masculinity, Megan Vokey, Bruce Tefft, and Chris Tysiaczny give four attributes to the hyper-masculine male. The very first attribute regards sex and women. "First, calloused (insensitive) attitudes toward sex and women is defined as the belief that intercourse with women is a source of male power and female submission, and that sex is acceptable without emphatic concern for the female's subjective experience" (Vokey, Tefft, and Tysiaczny 563). From the cover of Ashley Tisdale, to her interview, to any other article or image in the magazine, women are displayed as objects of desire. Laura Mulvey named this process of representing a woman as a beautiful object of desire as fetishistic scopophilia (Rose 161). Because women are depicted as objects, they position the reader to desire any and all women within the magazine. Because of this, the interpellated audience, as well as the magazine's ideal masculine male, is heterosexual. |

| In her analysis of GQ, Melinda Tankard Reist provides commentary on sexism within the magazine. By discussing the depiction of all four men who won the '15th Annual Men of the Year Awards' in suit and tie, while the only female winner, Lana Del Rey, is depicted in the nude, she argues that women of GQ are constantly presented as objects for the male viewer. "While the titled men appear as sophisticated citizens of the world, achieving important manly things, Del Rey exists only for male gratification and pleasure" (Reist 11). Although Reist argues that women are presented in a very similar fashion as the women in Maxim, I have found that while women are also depicted as sexual objects within GQ, it is not as frequent, and definitely not their only purpose. Women are given slightly more agency and power within the magazine, as can be seen by the article regarding women in the military. Titled "Natural Born Killers," the article provides examples of how women in the military more than prove their equality to men on the battlefield. An interesting article with an even more interesting theme, GQ seems to provide material suggesting respect for women.

|

|

| According to Feminist scholar, Theresa L. Geller, 'tough chicks' in film "having refused the heterosexual imperative of citizenship, according to the state, pose a profound threat to the very survival of the nation because the nation conceives itself as heterosexual" (Geller 14). Playing with that idea of tough women posing a threat to the nation, GQ uses the female soldiers to point out how women outside their usual gender roles do not threat the nation they serve, and deserve respect instead of fear. Not consistent with other men's magazines, and certainly not consistent with Maxim, this article plays into the notion of gentlemen reading Gentlemen's Quarterly. When visualizing masculinity, the article and the magazine in general do not advocate for men to see all women as natural born killers, nor do they advocate the visualization of women as sex objects. Instead, masculinity in GQ is seen as being heterosexual, but not necessarily dominant to femininity. Placing women as men's equals begins a process of change that R. W. Connell asks for in her work on masculinities. She "invit[es] men to end men's privileges, and to remake masculinities to sustain gender equality" (Connell 1817). GQ's article shows that men must be able to take care of a woman that offers herself up to them, but must also know how to respect a woman and become the gentleman they've been reading about in the magazine. Though heteronormativity is prevalent within both magazines, each one takes different steps to defining and visualizing masculinities within their texts. |