Visualizing Masculinities Within Maxim and GQ

Tony Irizarry

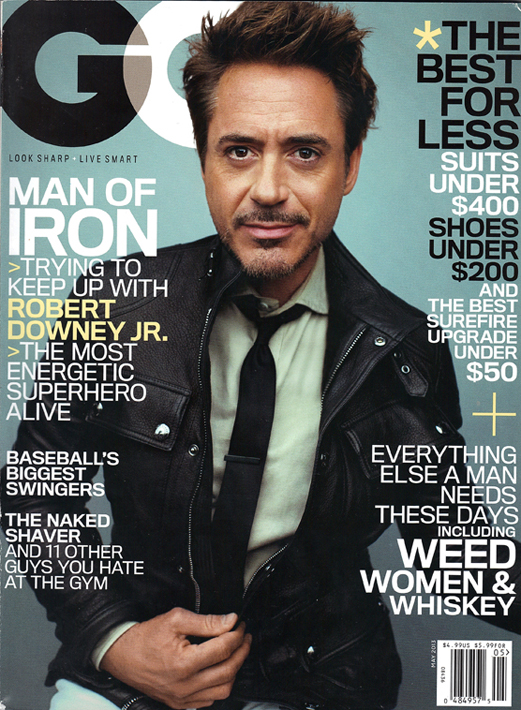

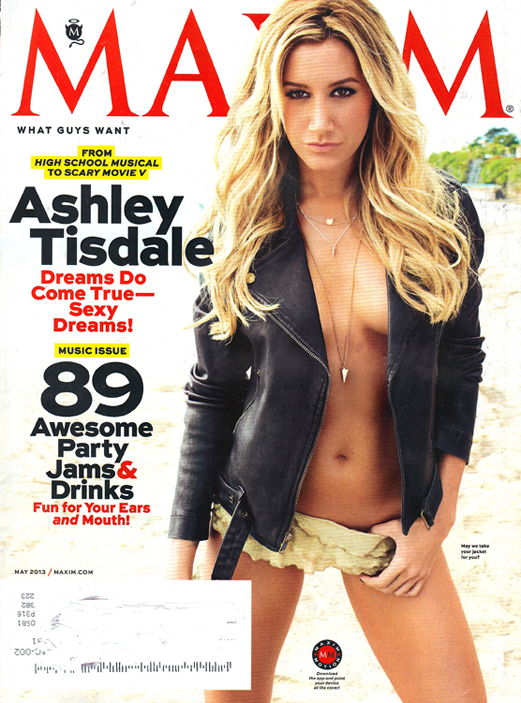

"Lifestyle magazines emerged for men in order to ease their growing anxieties and uncertainties about masculinity, as well as provide some direction about what is manly in late modernity" (Ricciardelli, Clow, & White 66). As pointed out in Rosemary Ricciardelli, Kimberly Clow, and Philip White's article regarding hegemonic masculinity in men's lifestyle magazines, lifestyle magazines for men are a relatively recent phenomenon, but have become quite popular over the past few decades. Maxim, a men's lifestyle magazine that has been in circulation for the past 16 years, provides a heteronormative message that began with its original slogan: "The best thing to happen to men since women." Changed now to "What guys want," Maxim still shows readers that it is a magazine made by heterosexual men for heterosexual men through its ads, articles, and consistent display of scantily clad women on the cover. GQ takes a slightly different approach to its style. Switching between male and female celebrities on the covers, GQ focuses on looking good, living well (by GQ's standards), and less so on women than in Maxim. Both magazines differ in content, but both provide for the masculine American male.

The two magazines provide excellent material to examine through a range of communication analyses. By observing different signs within each magazine and their relationship within the texts, ideas surrounding power and knowledge around masculinity begin to circulate. Bethan Benwell seems to ask the same questions and produce a similar analysis of masculinities in lifestyle magazines as my own in his work, Ironic Discourse, although he focuses on British magazines. How does each magazine visualize masculinity? How do their ideas of masculinity compare or contrast to one another? What audience is interpellated by each magazine, and what audience, if any, is interpellated by both? By analyzing the covers, advertisements, and articles of the magazines through a combination of social semiotics, psychoanalysis, and discourse analysis, I plan to answer these questions and decipher how masculinity is depicted within the covers of Maxim and GQ.

Two men's lifestyle magazines with very distinct styles, Maxim and Gentlemen's Quarterly create two different ideologies surrounding masculinity in America. From the moment one gazes at the cover of the magazines, he is presented with what seems to be opposing mottos from each; Maxim's slogan is "What guys want," while GQ boasts "Look sharp, live smart." Several scholars of masculinity and hegemony have concluded that it is impossible to attribute masculinity to one formula or set of guidelines. (Gruss 193; Moller 275). A universal, hegemonic definition of masculinity does not exist, and instead, ideas of masculinity are visualized differently within each lifestyle magazine. For my project, I will compare and contrast how masculinity is visualized in Maxim and GQ. By analyzing the cover of each magazine's May 2013 edition, as well as several images and articles within them, I will determine how each magazine visualizes masculinity, and what that means within American society.

Analysis

Works Cited

a class taught by Bob Bednar in the Communication Studies Department at Southwestern University