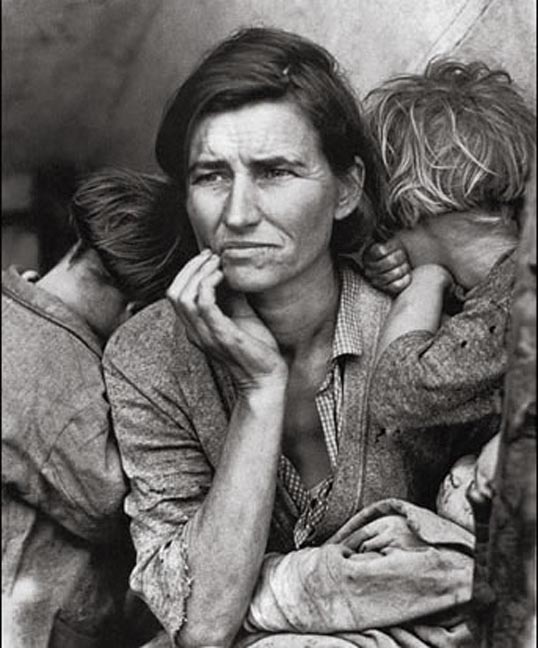

| One of the fundamental reasons this image works is because it conjures up the image of the Madonna and Child. It represents enduring value while also representing the zeitgeist. This image has come to represent the zeitgeist of the Great Depression. Hariman and Lucaites say, "Taken within the context of the Great Depression, it is not difficult to see how the photograph captures simultaneously a sense of individual worth and class victimage. The close portraiture creates a moment of personal anxiety as this specific woman, without name, silently harbors her fears for her children, while the dirty, ragged clothes and bleak setting signify the hard work and limited prospects of the laboring classes. The disposition of her body and above all, the involuntary gesture of her right arm reaching up to touch her chin communicates related tensions. We see both physical strength and palpable worry: a hand capable of productive labor and an absent minded motion that implies the futility of any action in such impoverished circumstances. The remainder of the composition communicates both a reflexive defensiveness, as the bodies of the two standing children are turned inward and away from the photographer (as if from an impending blow), and a sense of inescapable vulnerability, for her body and head are tilted slightly forward to allow each of the three children the comfort they need, her shirt is unbuttoned, and the sleeping baby is in a partially exposed position" (Hariman & Lucaites). When the public views this image, it is unclear where the father is, therefore the viewer is interpellated into the paternal role because there is an emotional connection between the viewer and the people in the photograph that has already been set up by the photographic dynamic (ibid). Hariman and Lucaites say, "This position outside the image also doubles as a place of public identity, for the viewer is always being defined as part of a public audience by the photograph's placement in the public media, while the public itself never can be seen directly. Thus, the public is cast in the traditional role of family provider, while the viewer becomes capable of potentially great power as part of a collective response. The mother's dread and distress call forth the patriarchal duty to provide the food, shelter, and work that is needed to sustain the family, while the scale of the response can far exceed individual action" (Hariman & Lucaites). The mood of this particular period in history is perfectly captured in this photograph. |  |

|

This iconic image of the American flag being raised at Iwo Jima was taken by Joe Rosenthal in 1945. In their article "Performing Civic Identity: The Iconic Photograph of the Flag Raising on Iwo Jima" Robert Hariman and John Lucaites say, "Public perception was immediate and resounding. The Times-Union of Rochester, New York, compared it to Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper" (Hariman & Lucaites 363). They go on to say, "Photographs from the war were numerous, of course, but none evoked such an immediate, positive reaction, and only few have come close to withstanding the test of time" (Hariman & Lucaites 363-364). What I will now work through is the question of why. Hariman and Lucaites say, "This rich articulation of civic action in the Iwo Jima photograph provides performative resolution of the tension between liberalism and democracy in U.S. post-war public culture. The varied appropriations of the image across successive generations demonstrate how liberal democratic public life is continually redefined in respect to an array of attitudes ranging from civic piety to cynicism" (Hariman & Lucaites 364). This fits their prescription that an iconic image "enacts the constitutive function of public discourse and coordinates multiple transcriptions of the historical event to manage fundamental contradictions in public life" (Ibid). This image works because it shows people working together in a common struggle against the opposing forces. This images brings up an important point. Regardless of the content, the image works because of the composition. The flawless composition coupled with the context has made this image one of the most iconic images that exists today. This image represents the zeitgeist, but it is also timeless and that balance between representing the zeitgeist and also maintaining the ability to be timeless is perfect in this image. |

Across these images, it is clear that iconic status can be achieved by setting up an emotional relationship between a viewer and the image. Hariman and Lucaites say, "Any iconic photo structures relationships between those in the picture and the public audience; indeed, that rhetorical relationship is the most important appeal in the composition and the primary reason that the images can function as templates for public life" (Hariman & Lucaites). It takes specific photographic techniques to create this emotional relationship. The viewer has to be able to become involved. We become involved as the provider figure in Lange's photo of the Migrant Mother and we become part of the victorious flag raising effort-just like those soldiers (who got through the battle firsthand) the American people got through the battle remotely.

|

Works Cited

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. "Performing Civic Identity: The Iconic Photograph of the Flag Raising on Iwo Jima." Quarterly Journal of Speech 88.4 (2002): 363-92. Print.

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2011. Print.