|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What Makes Iconic Images Iconic?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

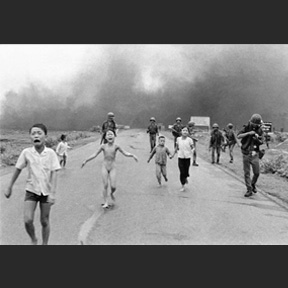

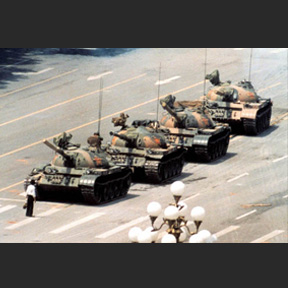

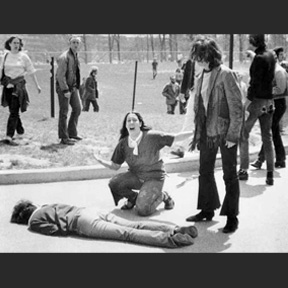

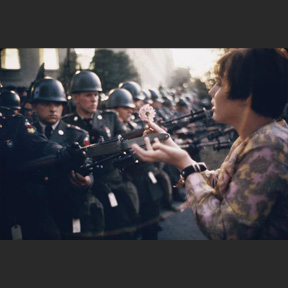

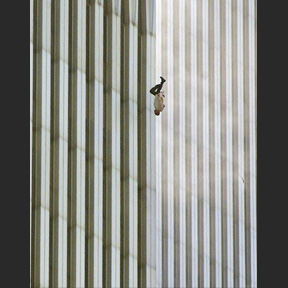

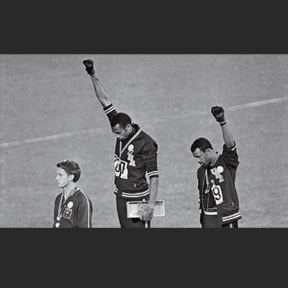

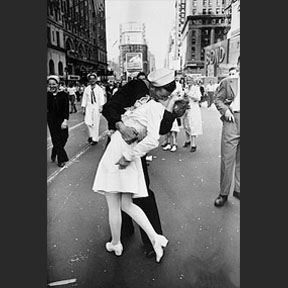

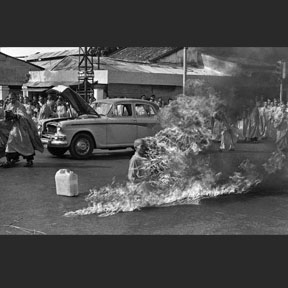

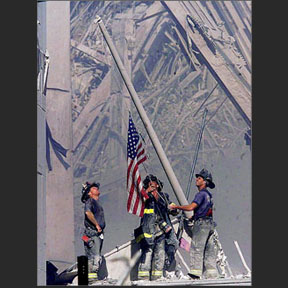

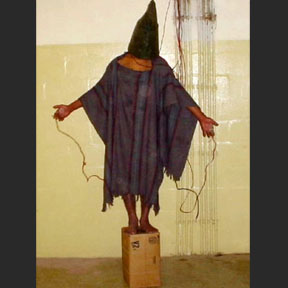

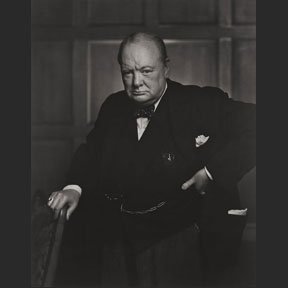

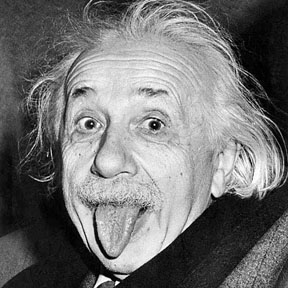

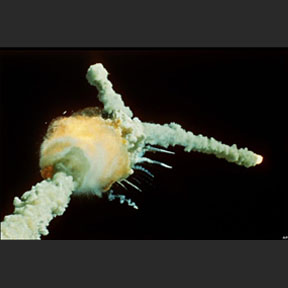

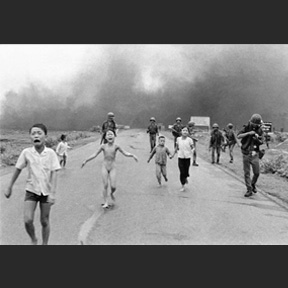

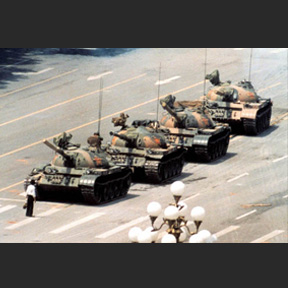

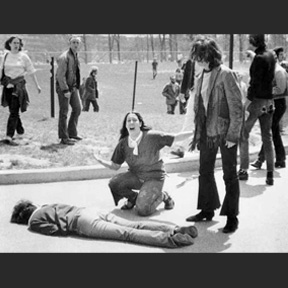

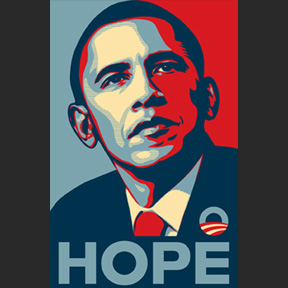

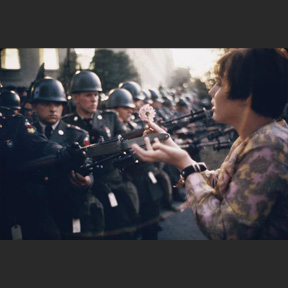

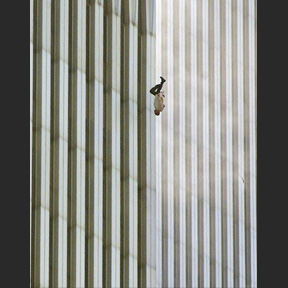

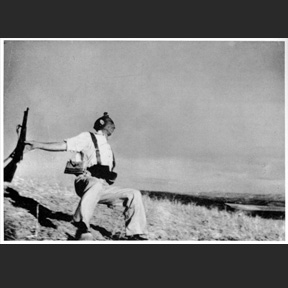

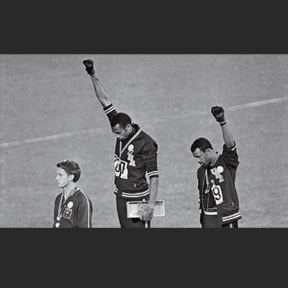

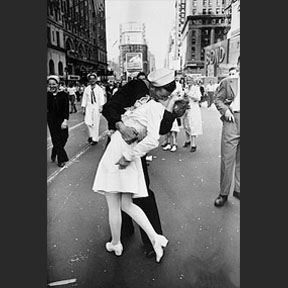

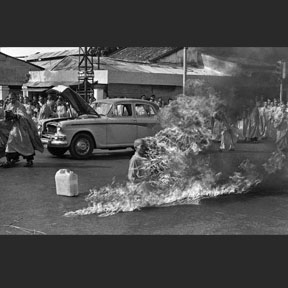

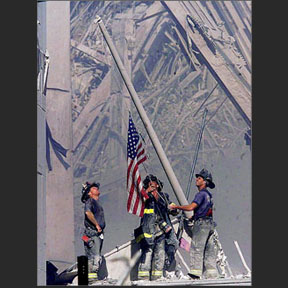

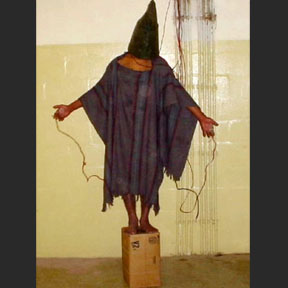

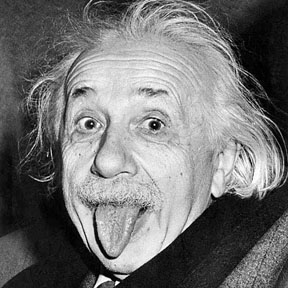

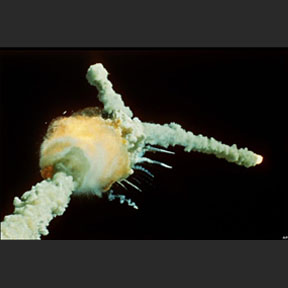

A photographic iconic image captures an event or a moment in our history, which is then available for Americans, as well as the world, to revisit again and again. The image will be referenced on the event anniversary, similar occasions, teaching exercises, used as warnings or to reminisce or evoke important collective emotions; anytime the moment is discussed. Many of our photographic iconic images have been produced and reproduced so often that they are instantly recognizable to everyone. They have and will withstand the test of time and all the true photographic iconic images will outlast the photographers as well as the persons photographed. Time will march on, but these photographic iconic images will freeze those moments, whether horrific or heroic, breathtaking or heart wrenching. "[An] important characteristic of iconic images is that they capture an exact instant and can't possibly be repeated," said John Loengard, a former Life magazine picture editor (Eddie Adams. Time) . He identifies the two most iconic pictures from this century are the hooded prisoner at Abu Ghraib and the falling man from the World Trade Center. Hariman and Lucaites say, "We define iconic photographs as photographic images produced in print, electronic, or digital media that are widely recognized, are understood to be representations of historically significant events, activate strong emotional response, and are reproduced across a range of media, genres, or topics" (Hariman & Lucaites 366).

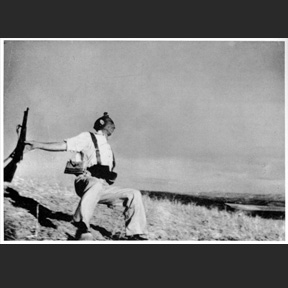

Iconic images are woven into the tapestry of our culture and the impact on public opinion is a key element of a photographic iconic image. When a photograph evokes strong emotion in the vast majority of the public, this is when an image could become iconic. A photograph could be documenting new social knowledge and the interplay between the photograph and the audience is what determines the iconic status. The photographic iconic image is then destined to define an event, a moment in history, a person or possibly a large group of people. Hariman and Lucaites say in their book No Caption Needed, "Our iconic memories are intensified depictions of the past and rich resources for living in the present; they help us to withstand the shocks of living amidst the competing tensions of freedom and necessity, self-consciousness and social determination, liberal personality and democratic polity. They provide models for action and assurances that we need not lose what we value most." (Hariman & Lucaites 94) Although, these photographic documentations help us to understand an event, person or group of people, it could be more complex that just witnessing our history. Eddie Adams is the AP photojournalist who took an iconic photograph during the Vietnam War, which many have identified as a catalyst that turned the sentiment of the general American public against that war. Adams said, "I won a Pulitzer Prize in 1969 for a photograph of one man shooting another. Two people died in that photograph: the recipient of the bullet and General Nguyen Ngoc Loan. The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera. Still photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world" (Eddie Adams). He goes on to lament taking the photograph explaining it only tells half the truth (ibid). There are inevitably times when the photographic iconic image tells a half-truth or one side of the story.

There is a critical emotional component to the photographic iconic image. Life photo editor, Peter Howe says, "I think the most important common denominator is that they strike us on a very deep emotional level, and the emotions are usually some of the deepest emotions that a human being can feel: heroism, fear, grief, joy," (Peter Howe. Time). Howe's career has included stints as director of photography at Life magazine and picture editor at The New York Times Magazine.

The following is an explanation of how iconic images work within the public sphere. Hariman and Lucaites say, "Iconic photographs perform several important functions in public address. They must be experienced within the ordinary routines of life such as browsing through magazines, looking at coffee table books, and surfing the web. They reflect social knowledge and dominant ideologies; "they shape understanding of specific events and periods; they influence political action by modeling relationships between civic actors; and they provide figural resources for subsequent communicative action" (Hariman & Lucaites 366). Achieving the status of iconic is intricately connected to public perception of an image because they interpellate a form of citizenship that can be imitated. Hariman and Lucaites say, "One reason images have become iconic is that they coordinate a number of different patterns of identification within the social life of the audience, each of which would suffice to direct audience response but which together provide a public audience with sufficient means to comprehend potentially unimaginable events" (Hariman & Lucaites 367). Iconic images continually adapt to the judgment over the years. Furthermore, iconic images situate life in the present within a formal composition and enduring context of meaning safely secured from change (artistic excellence, formal elegance, strong realism, focus on vernacular practices, foregrounding of powerful emotions, alignment of historical process, individual agency, collective purpose).

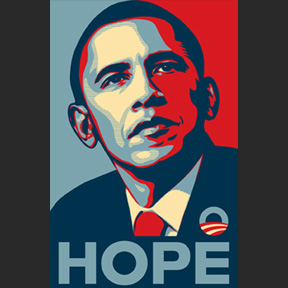

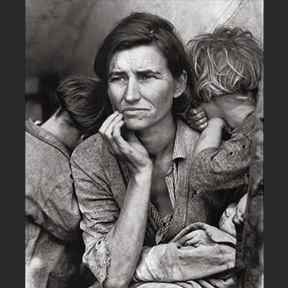

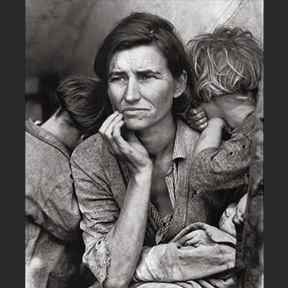

Iconic photographs are "(1) recognized by everyone within a public culture, (2) understood to be representations of historically significant events, (3) objects of strong emotional identification or response, and (4) regularly reproduced or copied across a range of media, genres, and topics" (Hariman and Lucaites 37). In their article, "Performing civic identity: The iconic photograph of the flag raising on Iwo Jima," Hariman and Lucaites say, "One reason images become iconic is that they coordinate a number of different patterns of identification within the social life of the audience, each of which would suffice to direct audience response, but which together provide a public audience with sufficient means to comprehend potentially unmanageable events" (367). Iconic images become iconic not only because of the power of the image, although that is certainly a contributing factor, but also, in order to become iconic, images must be indicative of or responding to an event happening in culture. For instance, Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother photo became an iconic image of the Great Depression. It would be impossible for that image to become iconic if it did not stand for a significant event in history. Without that tie in to the people, this images would never become iconic.

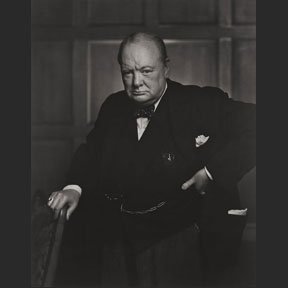

I am attempting to find a common thread in these images, which are all iconic, in the hopes of gaining insight into what makes an iconic image. Hariman and Lucaites say, "Our iconic memories are intensified depictions of the past and rich resources for living in the present; they help us to withstand the shocks of living amidst the competing tensions of freedom and necessity, self-consciousness and social determination, liberal personality and democratic polity. They provide models for action and assurances that we need not lose what we value most" (Hariman & Lucaites 92). They go on to say, "The iconic photo enacts the constitutive function of public discourse and coordinates multiple transcriptions of the historical event to manage fundamental contradictions in public life" (Hariman & Lucaites 364). Iconic images fill a cultural role that we need in society. We need iconic images to define an event, to mediate, to educate, to affect perception of an event and to connect us as a society.

|

Works Cited

Adams, Eddie. "General Nguyen Ngoc Loan." Time. Time Inc, n.d. Web. 3 May 2014.

Almond, Kyle. "What Makes An Iconic Image Unforgettable." CNN U.S. Cable News

Network, n.d. Web. 2 May 2014.

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. "Performing Civic Identity: The Iconic Photograph of the Flag Raising on Iwo Jima." Quarterly Journal of Speech 88.4 (2002): 363-92. Print.

Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2011. Print.