|

|

Urry posits that the expectations of museum visitors have changed in recent decades. "No longer are visitors expected to stand in awe of the exhibits. More emphasis is being placed on a degree of participation by visitors in the exhibits themselves." (1990, 130). Eilean Hooper-Greenhill exhorts the post-modern museum to focus more on audience by "involving the emotions and imaginations of viewers" because modern cultural organizations must address identity and subjectivity. "Subjectivity needs to be understood as something in process, and not as fixed and autonomous, outside history" (Hooper-Greenhill 2006, 142). She acknowledges that museum and gallery exhibitions have in some cases become "more informal, more lively and offer more possibility for mental and physical interaction" (2000, 6) based in part on advancements in learning theory, but also because this is what visitors want. However, Hooper-Greenhill exhorts that revisionism in the western world makes the modern museum a site of cultural struggle, and "as a result, the stories that are told in museums of history, culture, science and beauty are no longer accepted as naturally authoritative. The modernist museum is being reviewed, reassessed, and reformulated to enable it to be more sensitive to competing narratives and to local circumstances; to be more useful to diverse groups" (2000, 141). She suggests that modern communication and learning theory, epistemology and cultural politics "position the museum viewer/learner as both active and politicised in the construction of their own relevant viewpoints. The post-museum must play the role of partner, colleague, learner (itself), and service provider in order to remain viable as an institution" (2000, xi). She suggests that the museum of the future "may be imagined as a process or an experience" which rather than upholding the values of objectivity, rationality, order and distance ... will negotiate responsiveness, encourage mutually nurturing partnerships, and celebrate diversity" (152-153).

Hooper-Greenhill acknowledges that museum visitors are not static participants in all the museum's institutional practices, but inherently bring some agency to the experience.

"Meaning is produced by museum vistors from their own point of view, using whatever skills and knowledge they may have, according to the contingent demands of the moment, and in response to the experience offered by the museum" (2000, 5).

If the formalist, slow-changing regimentation of traditional museums and galleries is acknowledging the need to modernize and renegotiate their subjects, it would seem reasonable that the consumer-driven tourist market of caving may be doing so as well, if under less formalized, theory-driven terms. In fact, it seems that the National Recreation and Park Association has recognized for some time the need to negotiate various tourist desires for authentic interaction while still maintaining their own objectives. In a biography of Stephen Mather chronicling his accomplishments in establishing the National Parks System, the NRAP points out how at odds the two poles would become. "Thus in its [NPS] policies toward the great parks, the agency was at the same time a booster, a professional land manager, and a priest of American nature worship. Although it was not quite the problem it would later become, it was no mean feat to steer a safe course between preservation and mass use, between boosterism and professionalism, and between the lowest of park taste and the most refined" (www.nrpa.org).

If, as Stacy Warren argues, "popular culture is, to a considerable extent, a commodity," but being primarily concerned with the circulation of meanings, then the possibilities and products become "the cultural resources from which people, through acceptance, negotiation, resistance and evasion, form their own popular culture" (1993, 180). While caving, whether recreational or as tourist activity, may not often be thought of as part of popular culture, it, and its attendant practices and imagery, fall into the margins as such. Therefore, hegemonic incorporation becomes a constant necessity within tourism practice as "the resources of mass-mediated culture can ensure their popularity only by making themselves inviting terrain for this struggle" (ibid). It is imperative then, to recognize what the tourist wants. "The tourist critique of tourism is based on a desire to go beyond the other 'mere' tourists to a more profound appreciation of society and culture ... all tourist desire this deeper involvement with society and culture to some degree; it is a basic component of their motivation to travel" (MacCannell 1976, 10). Tourists want to be more than tourists; they want to be travelers. Moreover, they may want to be a specific type of traveler, and will appropriate opportunities to structure their own performance of tourism. In her introduction to Architecture and Tourism (2004, 2), Lasansky cites Edensor's study (1998) of tourists performances at the Taj Majal as having demonstrated that "multiple and often competing narratives can be sustained within any single locus" validating the agency of the individual tourist.

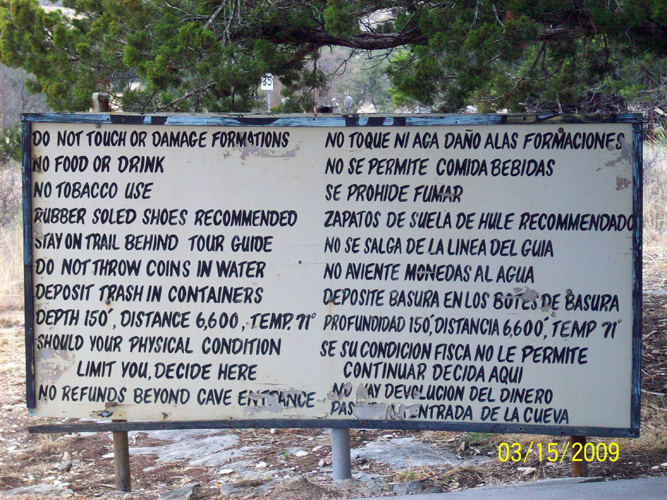

Cave tourists want to become travelers; they want to make their own cave art, they want to get off the beaten path, they want to appropriate the awe-inspiring landscape by really 'knowing' and preserving it. While their preferred subjectivities may not be exactly 'oppressed', they are suppressed by the undeniable power of the traditional apparatus and technologies of show caves. Many of the regulatory practices make it impossible for the artist photographer, the discovery explorer and the environmental scientist to find satisfaction in the subjectivites proffered. Like vistors to the Taj Majal, cave visitors will seek out spaces of resistance in which to perform their own version of tourist-traveler. To accommodate the changing subjectivity of the post-modern cave visitor, while protecting their livelihood and preserving their landscape, show caves are, and must continue to renegotiate practices and products which fulfill the quest for authenticity of the artist photographer, the environmentally conscious scientist, and the discovery explorer. It behooves the cave owner to participate in the negotiation of such resistances so that they ultimately profit both parties. "Tourism always stands within the cultural and economic politics of its environments and the historical development of the tastes and habits of the ever-increasing numbers of tourists. At the end of the day, the preferences of the tourists and how they are changing must be understood ... tourism is a co-creation of tourists, entrepreneurs, and designers, and this threesome needs to be understood together" (Greenwood 2004, xvi).

[ Back ] | [ Continue Tour ] |