|

|

The landscape of the cavern can be seen as art, which modern tourists capture most often in photography, whether in recognition of the civic sacred or in a moment of simple inspiration or speechless awe. As early as 1792, Englishman William Gilpin rhetoricized "picturesque travel" equating landscapes with a near-religious experience, very similar to the "punctum" elucidated by Barthes that may be captured in photography. Gilpin wrote of the awe stirred in the public "when some grand scene, though perhaps of incorrect composition, rising before the eye, strikes us beyond the power of thought ... we rather feel, than survey it" (Halloran & Clark 2006, 143). In "Adventure is Underground," William Halliday suggests such a moment of punctum as well when he describes looking up from a tunnel in Carlsbad's Lower Cave into the Big Room, "The spectacle was so awesome that it could not be imagined. It was one of the superb moments in my life--and my life has been a splendid one, full of color and magnificence" (1959, 135).

While the power of culturally circulated photographs may have brought

the tourist to the site, the power of making their own photographs

validates the tourist experience. "With your camera, you are able to

'capture' and consume scenery and preserve vacation memories ...

Certainly, photography gave tourists a language through which they could

describe and appreciate the environment surrounding them ... to explain,

even justify, how and why they visited a particular place" (Corbett,

2006, 139). Urry outlines photography's central characteristics, which

(among others) includes photography as a means of "transcribing reality"

by furnishing evidentiary proof that things really are as the traveler

says they were (1990, 139). However, he also describes how photo taking

may be insidiously participatory in technologies that structure how the

tourist makes meaning of even their personal trip photos. Urry suggests

that photos involve obligations. "People feel that they must not miss

seeing particular scenes since otherwise the photo-opportunities will be

missed" (1990, 139), which is the motivation behind staging special

viewing areas and tour guide stops. A knowledgeable guide may even tell

a visitor where a "good photo opportunity" can be had or offer to take

the photo so the tourist may include themselves in the scene.

While the power of culturally circulated photographs may have brought

the tourist to the site, the power of making their own photographs

validates the tourist experience. "With your camera, you are able to

'capture' and consume scenery and preserve vacation memories ...

Certainly, photography gave tourists a language through which they could

describe and appreciate the environment surrounding them ... to explain,

even justify, how and why they visited a particular place" (Corbett,

2006, 139). Urry outlines photography's central characteristics, which

(among others) includes photography as a means of "transcribing reality"

by furnishing evidentiary proof that things really are as the traveler

says they were (1990, 139). However, he also describes how photo taking

may be insidiously participatory in technologies that structure how the

tourist makes meaning of even their personal trip photos. Urry suggests

that photos involve obligations. "People feel that they must not miss

seeing particular scenes since otherwise the photo-opportunities will be

missed" (1990, 139), which is the motivation behind staging special

viewing areas and tour guide stops. A knowledgeable guide may even tell

a visitor where a "good photo opportunity" can be had or offer to take

the photo so the tourist may include themselves in the scene.

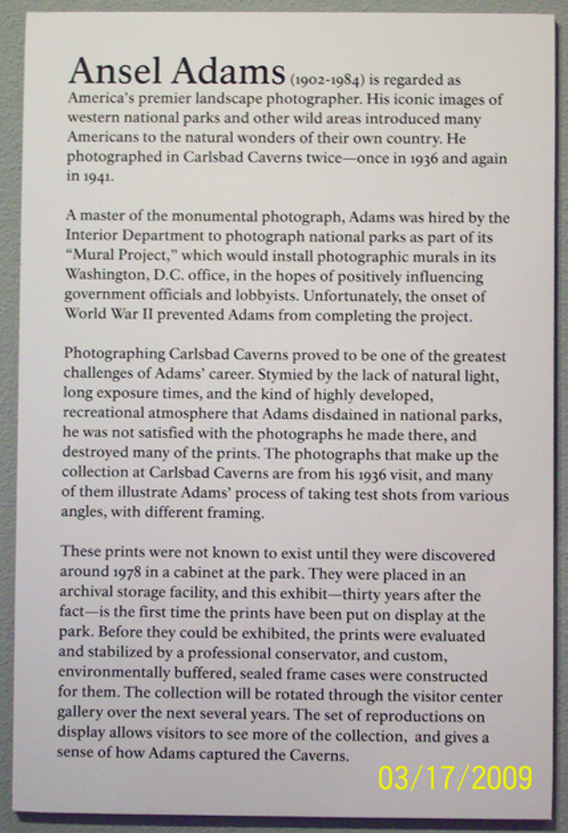

Institutionally produced photographs are employed in advertisement and exhibited in most caves, creating discursive formations in history, science and art that subjectify the tourist before and during the tour, but institutions may also participate in circulating photos and other artwork that acts as cultural currency. Carlsbad Caverns, with its own dedicated gallery, is a prime example. Certain visual images, whether made professionally or privately, whether modern or an antiquity, exchange ownership and gain agency through the creation of their own biography. An image that may begin as a privately held representation is donated to or acquired by the curator of the gallery, and because the curator has deemed it to be worthy, it is placed on display. The recontextualization of images (or objects) into the gallery defines these visualities as 'art' as well as co-constitutes a tourist subject who can then recognize his own photography (or painting or sculpture) as art also. Souvenir imagery, be it in the form of photos, postcards, key chains or t-shirts, confirm and/or certify the tourist's experience, and in doing so, are deposited into the visual economy as well.

|

|

As noted earlier, photography, souvenirs and other visualities produce a

collective gaze which "celebrates togetherness in visiting, which

focuses on enjoyment and activities among and between visitors rather

than between visitors and the environment" (Crang, 2005, 36).

But certain types of personal photography whose salience is on the

landscape, not the subject(s) in relation to the landscape, does produce

a different subjectivity due to its focus. According to Crang, such

distinction separates the subjectivity of the tourist from that of the

traveller, "who seeks an individual encounter with the place visited -

one that allows direct contact with the locale." Furthermore, Crang argues that these two subjectivites, or tendencies, are "reflected

in types of tourist photography: where collective tourism produces the

snapshot ... focusing on people," while the traveler tends toward "more

formally composed, 'arty' shots" (ibid). It is the latter which

receives the distinction of art and is placed in the gallery at

Carlsbad.

Crang argues that these two subjectivites, or tendencies, are "reflected

in types of tourist photography: where collective tourism produces the

snapshot ... focusing on people," while the traveler tends toward "more

formally composed, 'arty' shots" (ibid). It is the latter which

receives the distinction of art and is placed in the gallery at

Carlsbad.

In "Adventure is Underground," William Halliday claims that, "Carlsbad Cavern has never been properly described. Perhaps description of its myriad features is beyond the capabilities of human ingenuity" (1959, 135). But, if the artwork and photography housed in the small gallery at the modern Carlsbad Cavern Visitor's Center is any indication, the traveler artists are certainly trying.

[ Back ] | [ Continue Tour ] |