|

|

Beyond caving societies, and the cave site technologies themselves,

themes of cave conservatism and preservation have developed agency in

the world of cave art as seen in the survey of photography and through

the emergence of the NSS Salons. By materializing endangered cave

species (as in Robert Mitchell's photograph of the Texas Blind

Salamander or crystalline formations and cave popcorn as art, speleology

promotes its aims by reinforcing with the visitor and tourist that such

things must be preserved for the sake of art as well as science. An

effort that began as an attempt to photographically archive the history

of scientific discovery continues to utilize artistic visualities to

implement its objectives. In fact, the cave traveler-artist is often

and easily dually engaged as an environmentalist as well simply by means

of the production and dissemination of their art.

themes of cave conservatism and preservation have developed agency in

the world of cave art as seen in the survey of photography and through

the emergence of the NSS Salons. By materializing endangered cave

species (as in Robert Mitchell's photograph of the Texas Blind

Salamander or crystalline formations and cave popcorn as art, speleology

promotes its aims by reinforcing with the visitor and tourist that such

things must be preserved for the sake of art as well as science. An

effort that began as an attempt to photographically archive the history

of scientific discovery continues to utilize artistic visualities to

implement its objectives. In fact, the cave traveler-artist is often

and easily dually engaged as an environmentalist as well simply by means

of the production and dissemination of their art.

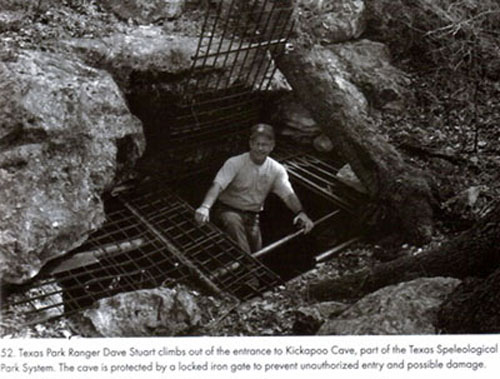

In discussing the appeal of modern tourist advertisements displaying "non-places" with luxuriously pristine, unpeopled landscapes, Thurlow & Gendelman (2007, 16) say audiences are "invited to imagine ourselves into these places knowing that our presence necessarily disturbs and changes the spaces. This is what gives these spaces their elusive quality. We are also reassured by those images of rapture that even when we have (temporarily) left the space, it remains empty of others. In echoing the neo-colonial discourses, this confirms the idea that these places are exclusively ours." While this mythology certainly speaks to the explorer subjectivity, it also addresses the scientist and especially, the environmentalist. The rhetoric of conservation naturalizes the view of pristine, empty landscapes undegraded by human interaction. Uncommercialized caves are gated and locked to prevent unschooled thrill seekers from debasing the caves ecosystem. Since 1985, Devil's Sinkhole in Texas has had tightly controlled access and "entry into the cave itself is restricted to scientists and researchers" (Pittman 1999).

|

Private caving requires membership in one of the cave societies, or at a minimum a recitation of previous caving experience, and cavers and spelunkers have become more reluctant to share their intimate knowledge of particular caves outside these societies. Well-versed in the conservationalist, environmentally sensitive ecoscience discourses, cavers find community in protecting their 'elusive spaces'. "Today many cavers are almost secretive about their caves and activities. They are not adventure seekers, but rather seekers after knowledge. They have learned not to talk very much about their caving activities, so caving has become a very low-key, exclusive means of studying a fascinating dark world" (Pittman 1999). |

Since relatively few cave visitors have the credentials of paleontologist, archeologist, or professional photographer, it can be difficult for the tourist to participate in the scientific subjectivity outside of accruing knowledge gained on site and off, about conservation of the karst. The motivated traveler category of tourist might consider joining a local caving society so that through active participation or the payment of dues, they receive the gratification of directly impacting our caves' ecological preservation. The option of physical interaction with caves whether show sites or wild, raises exponentially by admittance to one of these groups. But other resistance-birthed means of cave experiences for the environmentally-minded are becoming more widely available. Perhaps one of the most extreme versions of negotiated cave experience in the interest of conservation are virtual tours beginning to show up on the internet such as The Virtual Cave. Jack Burch might well be pleased to see the destructive effects of the tourist minimized by removing the physicality of their presence in his beloved caves.

[ Back ] | [ Continue Tour ] |