Toward an Environmentally-Minded Subjectivity in Carlsbad Caverns

by Dyana Shearer Kenison

Toward an Environmentally-Minded Subjectivity in Carlsbad Caverns

by Dyana Shearer Kenison

"The World that exists deep below the surface in Carlsbad Caverns

National Park is a subterranean marvel. Considered by many as the

Eighth Wonder of the World, it is one of twenty World Heritage Sites in

the United States." (From the Carlsbad, NM Chamber of Commerce

Magazine.) Regardless of whether you plan to take the two hour hike

down the Natural Entrance route, or the two minute elevator ride down

the 750 ft. rock shaft, from the moment you enter the National Park the

visualities encountered are mediated by specific institutional apparatus

using technologies which produce certain "social subjectivities" (Rose

2007, 181). An analysis of these apparatuses and technologies expose a

shift from traditionally articulated discourses that historically

served to transfer the awe of discovery into material form toward the

production of post-modern subjectivities concerned with consumption of the

cavern as a site of ecological preservation.

Before entering the Caverns themselves, tourists must first navigate the

Visitor's Center--a large, modern building in which numerous spaces have

been specifically designed to enact the formalized structure of the

caving experience. The first order of business is to decide which "tour"

you intend to take, and you must purchase tickets to do so. While there

is limited availability (often requiring advanced reservations) on

certain "ranger-guided tours" all visitors are encouraged to at least

take the "most popular option" of a one-mile self-guided stroll through

The Big Room. Long tour lengths with early last entry times, limited

guided-tour availability and an entry fee good for three consecutive

days assumes that a visitor may actually complete fewer tours in a

single day than desired. The three-day entry also presumes, and incentivizes,

visitors who expect more than a cursory surface experience during their

visit.

Visitors to the cave are informed what to see and how to see it by

other, taken-for-granted technologies. Along the cavern tour, some

12,000 variously colored lights in The Big Room alone were placed by a

professional stage lighting company to accentuate and highlight the most

interesting and beautiful of the cave formations. The otherwise

semi-dark route makes clear where the visitor should stop for optimal

viewing, and spotlights cave phenomena it is assumed they will want to

take pictures of. Bennett also notes, according to Rose, that

architectural plans within museums may have the "surveillance of other

visitors built into the design" (Rose 2007, 182). In the cave

environment, application of this technology appears in the planned

viewing stops at which visitors take advantage of the wider trail space

and the specialized lighting to take photos. In part, visitors are

encouraged to do so by surveilling other visitors doing the same. To a

certain degree, prior knowledge of which sights are worth photographing also

comes from cave advertisements and historical photos tourist have viewed

prior to or earlier in the tour. Most visitors wind up taking similar

photos from the same pathway-defined stop positions as earlier tourists

have done for 80 years, encapusulating a personalized (re)discovery

trope in a takeaway snapshot.

En route to the Natural Entrance, tourists must pass through an open

section of the Visitors Center with one large wall mural and multiple

freestanding rectangular displays emphasizing the science behind cavern

formation, cave ecology and the importance of the discovery of the cave

as a scientific resource and as evidentiary proof of the truth of

science's claims. In this space, as Rose explains, the cavern

curator(s) most optimally operationalize "discourses of culture and

science in their classifying and displaying practices" (Rose 2007, 182).

The cave visitor is schooled in the role a deeper undertanding of the

science of caves plays in impacting the local ecology and wildlife, preserving

watersheds and establishing a national research site.

In addition to such structured technologies which shape and limit

spectatorship, the Carlsbad Caverns National Park visitor encounters one

of the first visual enactments of formalized power structure while

waiting to purchase tickets. To the left of the waiting line is a large

display area that traces the history of the park rangers. Historical

pictures of past and current ranger uniforms prepare visitors to

encounter the rangers, emphasizing their authority in order to

naturalize an expectation of submissiveness on the part of the visitor.

A ranger escorts all visitors taking the elevator down to The Big Room,

and a pair of rangers meets all walking visitors at the beginning of the

Natural Entrance. These three gatekeepers provide a brief summary of

the park's history and confirm regulations regarding behavioral

expectations for "proper" engagement with the cave. The layout of the

cave and the architecture of its development as a tourist site make

clear that only certain types of engagements by the visitor are

allowable. Tour paths are easily identified by paved walkways, low,

fabricated stone walls and handrails, and any other route across cave

formations is made inaccessible. Several times along any tour route,

visitors will encounter additional rangers stationed as visible

reminders of the tour protocol, and expectations of conformance. Such

enactments help, as Bennet argues, to "regulate social behaviour by

producing docile bodies" (Rose 2007, 182).

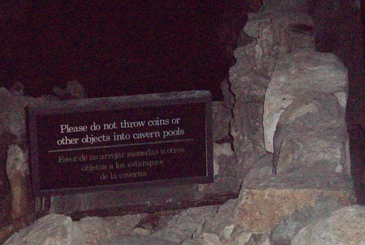

Lest there be any doubt, rules are further articulated by signage, such

as this warning not to leave the pavement and regulatory statements

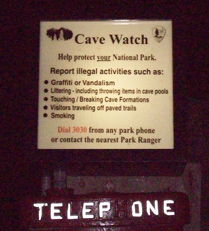

included in the audio tour guides. In fact, expectations of the

self-policing of the traditional nature experience mantra, "Leave

nothing but footprints, take only pictures" is highlighted by the

accessibility of prominent "Cave Watch" phones to call in any observed

rule-breaking to the nearest unseen ranger. As Rose suggests, the

subjectivity produced by such highly visible regulatory practices is a

"visitor that looks rather than touches" (Rose 2007, 189). Such

surveillance technologies also presume a subject with a naturalized

sense of ownership in, and desire to corporately affect preservation of

what one tourism guide advertisement identifies as "one of America's

greatest national treasures."

| Here, as Rose suggests, the "exhibition's practices of representation [are] made explicit" (Rose 2007, 187) as visitors preview the interpretive visual discursive that will continue to be reiterated in display signs along the cave tour paths and at length in the audio tour guide accompaniment. "Museums often collect objects that are meant to exemplify the way of life of particular social groups" (Rose 2007,180). In the cave environment, most displays collect information that describes the discovery, exploration and commercialization of the cave, historicizing the spelunker and early American miner/frontiersman. Additionally, as suggeted earlier, caves display the scientific methodologies of earth science classification, and representations of archeological and anthropological value. The cavern becomes a space for cultural enrichment and develops aesthetic presence because of its natural beauty. Historical narratives, art displays and a discursive emphasis on science help to "establish" Carlsbad Caverns as a national park and World Heritage site whose "outstanding natural and cultural resources form the common inheritance of all humankind," as suggested by a poster in the Visitor's Center gallery. By combining elements of the historical significance of the caverns with the scientific impact of its discovery and the cave's value as a source of art, the visitor is encouraged to take up the position of an ecologically sensitive preservationist. |  |

|

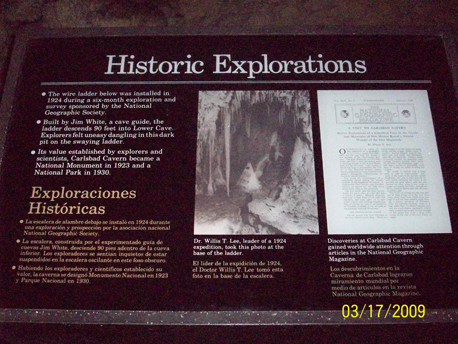

Historical significance is established by the ticket line Park Rangers exhibit (or earlier, as most tourist guides, pamphlets and advertisements engage this dialogue) and continues to be seen along the self-guided pathways. Specific sites of historical interest are set apart along the route by light up displays and numbered signs which tell the visitor which button to push to hear additional explanations of the sights and displays they are engaging with. Sekula argues that archives "are not neutral; they embody the power inherent in accumulation, collection and hoarding as well as that power inherent in the command of the lexicon and rules of a language..." and such archives derive their authority indirectly from the institutions enacting them (Rose 2007, 173). In the displays of Carlsbad Caverns, historical and scientific discursive apparatuses juxtapose to provide complexity in a curious moment of circular reference. The historical discovery of the cavern system is important for its ability to enhance scientific study, and this furtherance of science becomes an important part of the cavern's historical element. One example of the articulation of this ideaology can be seen in the preservation of an antique wire ladder anchored deep in one of the cave pits, and the attendant "Historic Explorations" display sign, complete with a copy of a 1924 National Geographic Magazine article that both describes and highlights the importance of exploratory efforts, and directly helped to propel the cave to National Landmark status. |

|

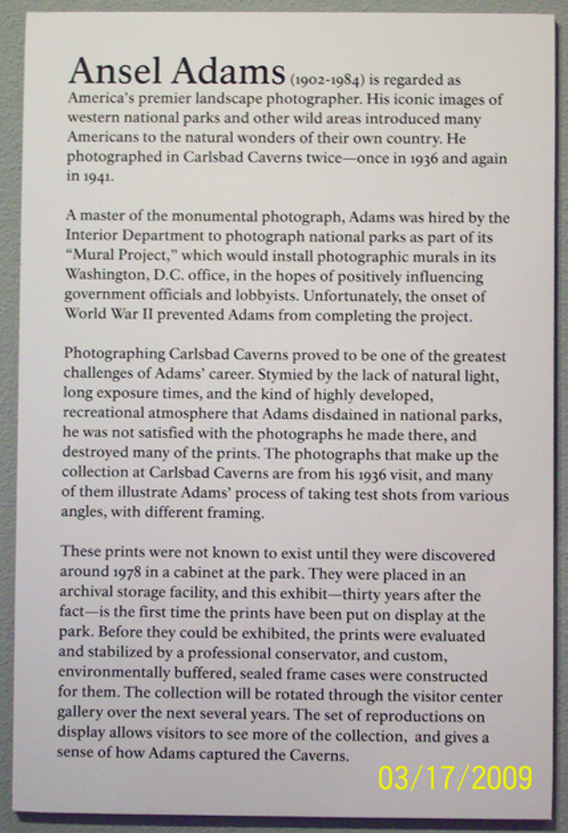

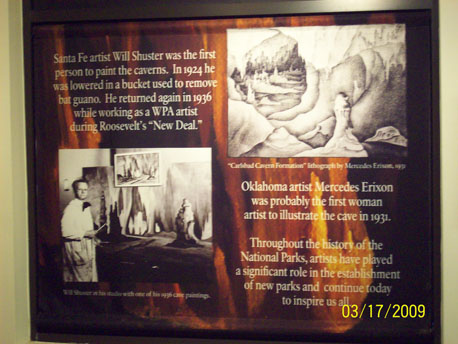

| In addition to offering the materialization of the cave's history and science as a form of "educational spectacle" (Rose 2007, 191) it may be argued that caves also subject visitors to instruction on how the "good eye" is composed (at least with respect to the aesthetic value of the cave landscape). Carlsbad Caverns is unique among tour caves for its use of a small art gallery to motivate the theme of the cavern landscape as art. Sketch artists, painters, sculptors and photographers--most famously Ansel Adams--have spent long hours during the past century trying to capture the majesty of the cave scenes. The circulation of their works serves to facilitate this discursive of the landscape as high art, and therefore worthy of preservation. Numerous photos, drawings, and sculptural depictions of the caverns are displayed as part of the "Visions Underground: Carlsbad Caverns Through the Artist's Eye" exhibit. This mini-gallery capitalizes on the aesthetic experience of the cave as re-experienced in the art display. While some of the collection has been purchased by the park and some are gifts from the artist, all presume the presence of an aesthetically motivated, artistically-inspired subject, likely to be interested in capturing or recreating such art themselves as well. Through primary discourses of art and science, visitors are interpellated into positions in which they, captivated by the splendor of the Cavern experience, and conscious of the historical value of such an experience, want to reproduce it, whether as exemplified by the personal photograph, or the gallery artists. Such works become part of a broader discourses, continually reenacted in iconic Carlsbad imagery. |  |

|

|

The artworks spill out of the gallery into other areas of the Visitor Center, like these backlit photos on the columns lining the gift shop and snack area which remind the visitor of the natural splendor of their recent tour while commingling with a highly commercialized area. The art displays help to ensure that the cave visitor never loses sight of the preeminent artistic value of the cave site.

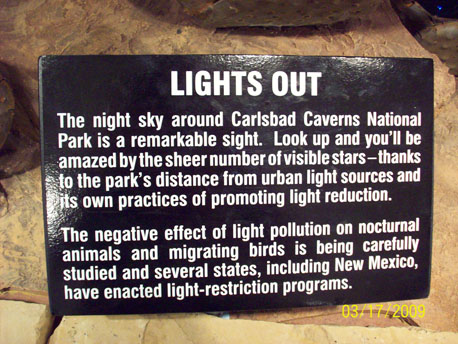

The gift shop includes other art whose sole purpose is to highlight a

discourse of conservation such as the contracted "Lights Out" sculpture.

Form and function literally combine to advocate for light reduction

efforts. A discursive shift toward a more ecologically minded consumer

can be seen enacted by Carlsbad in several specific ways. For example,

old signage combines with new in one gift shop display case to remind

visitors of the regulations protecting the bat populations and

preserving the cave for future visitors. A set of backlit displays in

one of the cave's oldest highlights, a concession area 750ft

underground, describes the current movement of the cavern's

self-produced discursive narrative toward a new emphasis on the

ecological preservation of its well-established artistic and scientific

value: that since the underground Caverns should be "almost exclusively

about this extraordinary cave experience" the underground concession

center must be "perceived and operated as a service center... minimizing

adverse impact on the Caverns."

Nowhere is the parks own struggling initiative toward this end perhaps more ironically operationalized that in the following trivial space:

One cobbled together sign stands between an "old-school" trash receptacle and a modern recycling bin. The sign was (as can be seen in an unaltered version elsewhere in the cavern) a simple self-policing request to keep the cave clean now appended by a request from the bats for their ecological preservation. The historical and artistic motivations enacted in the caverns over the last century are slowly being subsumed in the discourse of conservation--perhaps what Bennett would have called a "democratizing move" (Rose 2007, 183) on the part of Carlsbad Caverns National Park not as a representative of Big Brother, but of Big Bat.

Rose, Gillian.

2007. Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of

visual materials. 2nd ed. London: Sage.