The first participant, Annie, had a consistent theme in her choice of photographs. When asked how she chose what pictures to take, she said, "I ended up choosing everything that felt safest and most comfortable in my house, and most mine" (Harrison). Comfort and ownership figured prominently in every photograph and every discussion of the photographs. This corresponds to David Morley's assertion that, "home starts by bringing a space under control" (Morley 16). This was quite literally the case for the subject of most of Annie's photographs-her bedroom. She told me that she had very recently cleaned her bedroom, and would probably not otherwise have made so many photographs of it. The act of cleaning, ordering, and organizing is a manifestation of the desire to control a location. When someone purposefully organizes, it is an assertion of presence in and control over that area. In the pictures Annie presented everything was scrupulously clean and ordered.

In an effort to ensure that this was somewhat "genuine" I asked whether or not her room usually looked like this, and why she had felt the urge to present it in this manner. The cleaning was coincidental, but she did say that, "it hasn't felt this much like home before" further supporting the idea that some amount of control goes into claiming a space. In the case of her bedroom, which she identified as a very private sphere that only she and those she specifically invited occupied, this control was not over other people but over herself and her own possessions.

Her room is notably filled with "things." Scarves line the wall above the bed, the bed itself has a cover and an additional quilt at the foot (given the heat this is obviously an accessory rather than a necessity), photos and other pictures are arranged on the wall, and more photographs and small knick-knacks occupy the table. Hodgetss remarks on the human phenomenon of acquiring "special" objects, explaining, "objects provide memories and remind them of who they are and who they hope to be; the accumulation of objects involves the accumulation of being" (Hodgetts 296). This certainly proves to be the case in Annie's room. However, on a darker note, though in this instance all of these things are arranged in their place, there lurks the idea that these things, if unordered, would victimize Annie, and leave her feeling "out of control" at the hands of her own things.

Regardless, the threat of these things is neutralized by the order she has imposed upon them. Annie described a few individual objects, revealing that part of home for her was material possessions that she, by her use of them and by the memories invested in them, had given great value to. It is important to note that Annie lives in a house with two other women, and it is filled with the furniture and possessions of the woman they rent the house from. Tian writes, in a study on possessions in the work place, that peoples' "stuff" can, "overcome feelings of alienation and transience by making a personal mark" (Tien 299). Though this applies to navigating a workspace, it makes sense that, since Annie is a temporary resident in someone else's home she would make her mark via her possessions as a way of creating a sense of permanency. This becomes even more evident when one considers the connection the goods have to memory.

The first example of this is the quilt at the foot of the bed, already noted as extraneous.

She recently received the quilt from her mother, whom she is very close to. The quilt was made by a great-grandmother. Though she had no relationship with her great-grandmother, she found the idea of it being passed down to her very appealing and expected that she would build an attachment to the quilt. Epp speaks of the relation families can have with objects. Though the quilt, being handmade, was not purchased as w hole, the fabric, thread, and so on that make it were once commodities. Epp writes that, "families bring commercial products into the domestic space. Some of these objects become singularized (imbued with meaning and use) and caught up in the networks of existing spaces, objects, and identity practices that implicate the object" (Epp 824). This has happened to the quilt. It was used by different generations, inhabited different spaces, and now has come to Annie and is a part of her identity. What might be considered by others valuable for its aesthetic or functional aspects, for Annie, was valuable because of the sentimental attachment invested in it.

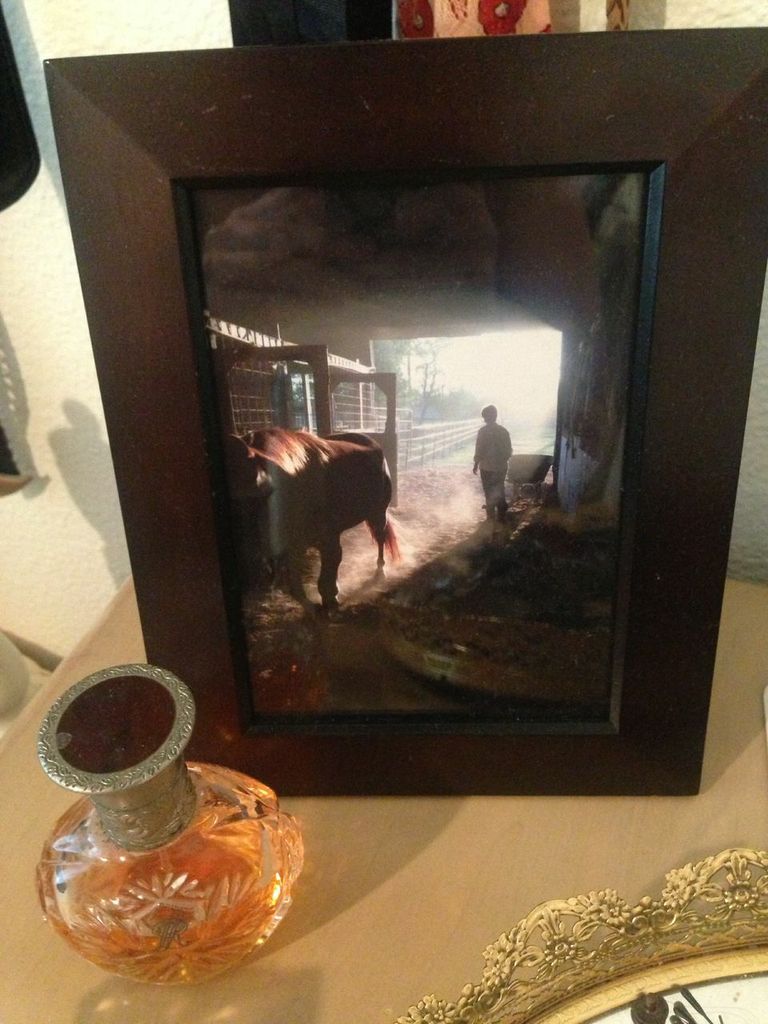

Another example of this is the railing of her bed frame, which she said she had since she was seven years old. Unlike the quilt, this object had memory-value, as did almost every single other object she mentioned. She pictured a perfume bottle, evocative because it conjured in her remembrances of her mother wearing that perfume when she was a child. Most telling, perhaps, was the emphasis Annie placed on photographs, specifically photographs of her childhood. In her words, "Sometimes home is the past...It's that whole concept of "days gone by," my childhood, if you just look at pictures, looks perfect" (Harrison). When pressed she asserted that her childhood was not perfect, which perhaps explains why these happy photographs would be so important.

The way she positions these photographs, prominently on the desk, but also close to her bed, indicates to me that they are primarily for her benefit. John Berger, in his essay "Uses of Photography" addresses this very private use. He suggests that, "The spectacle (of the photograph) creates an eternal present of immediate expectation: memory ceases to be necessary or desirable...The camera relieves us of the burden of memory" (Berger 55). This suggests a very purposeful role that photography plays. In Annie's case, since she prizes her childhood so highly, the photograph in a literal way brings the past to the present. Furthermore, the photograph has an implicit truth claim, an idea that it shows things "how they were." Since Annie suggested that her childhood was not ideal in many ways, the photograph offers proof that denies that fact, one she might repress on a daily basis. These personal photographs are primarily for her, in contrast to this is the "art" posted on the walls.

The pictures on the wall are large and would be at eye-level for someone standing. Though this benefits Annie when she walks in the room, it also suggests that she is showing the room to an imagined audience. She identified everything in the collage as having some sort of nostalgic, memory-based meaning for her, but also noted that, "This is an art I can do... I cannot draw but I can arrange things and make it look pretty" (Annie). This indicates that she ascribes value to being seen as artistic. Many of the pictures that she arranged were things given to her by friends, from birthday cards to photographs. Gifts are one way that consumer items are decommodified. As Belk writes, "since a gift is usually an expression of connection between people, it may take on sacred status" (Belk 17). His definition of sacred is complex, but the basic point is that the good evokes a connection with another person, which elevates the user's perceived value of the object in a way independent of what it is worth as a commodity. In summary, the items in Annie's room were mostly for her pleasure, as seen in their placement, and were all goods with which she had made an emotional investment.

This also evokes Morley's statement that, "A room can thus be best understood as a kind of objectified collective memory or mnemonic which "stores in the arrangement of its parts" how we behave in it...Their children, through learning to live in the rooms which their parents have furnished, learn the remembered values of their parents' memories" (Morley 20). Morley is speaking very broadly of how the spaces of the home constructs the way children (who later became adults) function in society. However, it corresponds that if Annie learned as a child to avoid rooms that were filled with conflict, she would continue to carve out spaces of safety in her adult life.

These safe spaces mark the "punctum" of the house that she lives in. She did not photograph the front of the house, or the kitchen, or the common room. Instead she focused on that which she loves, and which touches her deeply-the spaces she controls and creates. The mimicry of this childhood pattern is seen in how Anne interacts with her roommates in their common spaces, namely the bathroom, kitchen, and couch.

Annie shares the bathroom with one other person, but included a picture of her shower, explaining that she felt ownership over it because she spent the most time in it. This logic of ownership by proxy of time invested also showed itself in her portrayal of the living room, a photograph of the couch that was "hers." She said, "That's actually my couch...When my room wasn't clean it was my safe spot. If I needed to put my head phones in and ignore the world I could...I have to have the things that are mine (to feel at home)" (Annie). Again, the idea of home as a place where she can retreat from others surfaces, even if that retreat is in a common space.

Morley examines this idea of dividing up shared living spaces when analyzing how families watch television. He notes that families often have different areas in the home that each member has marked as her or his "space" for entertainment. This is the idea of the television set in the child's room, or "dad's chair" in the living room. By relegating members to their locations, conflict is avoided. In Annie's case, the fact that she and her roommate have an understanding of whose couch is whose (despite the fact that the couches in question belong to neither woman), they, "negotiate the occupation of separate (and often complementary) physical and/ or symbolic spaces" (Morley 91). Having a "spot" also creates a sense of "safety" from possible conflict for Annie. Also of note in her attachment to the couch is the inherent qualities it possesses that construct her relationship with it. In an ethnography of Ikea furniture conducted by Swedish scholars, they discussed the ways in which the physicality of objects dictates our use as a beginning point for analysis (Bjoerkvall). Annie noted that this couch was hers in part because she was taller than her roommate, and therefore her roommate habitually sat on the smaller couch.

Finally, Annie discusses home in terms of her mobility, and her ability to carve out space in public places. An obvious one is her car. According to Annie, "I realized home has become my car... I keep changing apartments and changing other things... My car is always an expression.. It feels really comfortable and safe." The car, similar to the carefully structured room, is a constant amidst change. The car is a strange phenomenon, because it provides a private environment for the user even though it is constantly moving through public areas that the user otherwise has no control over. Fraine argues that the car functions as a "primary space" or home, pointing out that they typically represent, "control, comfort, freedom, power, privacy and self-expression" just as homes do (Fraine 64). Annie's car, it is important to note, is very "comfortable." It caters to her, as the user.

The final way in which she relies on mobility for a sense of home is through her walks to "nature" for, "Since I was 13 or 14 I have brought...whatever plays music and walk out into the nearest wilderness." Everywhere she has lived she finds, "spots out in the wilderness that were mine." The idea that someone could own a field that is public place is interesting. She compensates for literal lack of control with the use of her music player, which gives her control over her sonic environment, allowing her to block out unwanted parts of the environment, such as the noises of traffic. Tien remarks on sound control as a means of controlling space in the workplace study, concluding, "These objects (music devices) were used defensively to avoid interferences with focused mental activities. Most commonly, these possessions altered the acoustic environment, providing a sound texture that surrounded and insulated the self" (Tien 300). The idea of a "sound texture" that "insulates" the self harkens back to Annie's prioritization of comfort and safety. She can achieve this even outside her home by using another material possession, the music player, to attune the environment to her emotions and thoughts.

In conclusion, Annie shows a close association of home and safety, and safety and retreat, time and time again. This is not abnormal. As scholar Tim Putnam wrote, studies of the home, "repeatedly throw up the same basic terms: privacy, security, family, intimacy, comfort, and control" (cited in Morley 24). Annie expressed these concepts primarily through her use and arrangement of material goods.