Contemporary men may be facing what many critics refer to as a "crisis of masculinity," in response to increased gender equality (Swami 61). However, Helene Shugart argues that this crisis is embodied in the concept of masculinity, and "Masculine gender identity is never stable; its terms are continually being re-defined and re-negotiated, the gender performance continually being re-staged" (Mangan in Shugart 281). In short, masculinity is constantly in flux. Shugart claims that gender is constantly struggling to reproduce itself in the face of complexities and ambiguities (281).

It would appear that there is a drive towards new ideals of beauty that help differentiate male and female bodies. There has been an emphasis on a strong aesthetic sense and fashion consciousness that is fueling a growing preoccupation with men's appearance (Swami 61). According to Shugart, objectification and commoditization of men and masculinity has infused our contemporary culture due to consumerism and our practices of consumption (281).

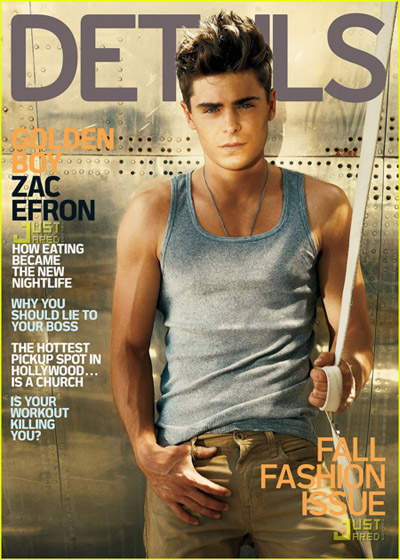

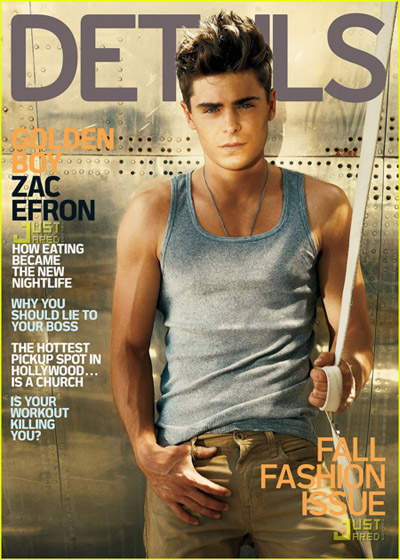

Commercial masculinity challenges normative masculinity by allowing men to become the objects of and for consumption through "male-on-male" gaze, which signals a large shift in the gendered "politics of looking" or what Susan Faludi refers to as "ornamentalism" (Shugart 285). This ornamentalism of men, leads to the feminisation and homosexualisation of normative masculinity by opening the door to insecurity and vanity, (Shugart 285). It invites attention from other men, producing what is called the homoerotic gaze (Hall 69). The rise of these sexualized images of males in advertising requires men to become an object of surveillant gaze through sexual evaluation (Aubrey 2). This practice disrupts the conventional practices of looking where "men look at women and women watch themselves being looked at" (Berger in Hall 69). Men are now objectified in ways that women historically have been.

Commercial media has "queered" all the codes of official masculinity by adding homosexual desire to images. According to Simpson, masculine portrayal is "passive where it should be active, desired where it should be desiring, looked at where it should be always looking (qtd in Hall 69). The homoerotic gaze is most profound in men's style magazines because the male reader is offered a multitude of visual images of shirtless or mostly naked male bodies advertising products. This "queering" of the male gaze disrupts traditional hegemonic masculinity. If heteronormativity is a cornerstone of normative masculinity, this feminizing feature of commercial masculinity calls heteronormative masculinity into question (Shugart 286).

Cultural critics have noted the emergence of new discourses of masculinity in the hegemonic cultural realm of most industrialized nations (Shugart 280). These changes pose a significant challenge to the historical discourse of normative masculinity. New trends in masculine performances and practices of strength, power, control and domination have blurred the line between masculinity and femininity.