|

Can't Touch This |

|

|

Can't Touch This |

|

My friend Andrew bought a package of film from the Impossible Project's website in March of 2010 and submitted a photo of he and his girlfriend. He was pleasantly surprised when it showed up on the site about a month later. "It's kind of weird" he said when I asked him about how he felt seeing his picture on a public site where anyone could see and save his private moment, or even claim it as their own (Kirk). He went on to say:

I was just really excited about being able to share my image, my positive experience with this new line of films with the larger community. Especially since so many of us thought we would never have this kind of film made available to us again. Yeah, the original photo will always mean something really personal to me, and no one who sees it or uses it for their own purposes will understand what it means to me or [my girlfriend], but the fact that it's out there and has the potential power to reach people all over the world, you can't deny, that's something pretty incredible. (Kirk)

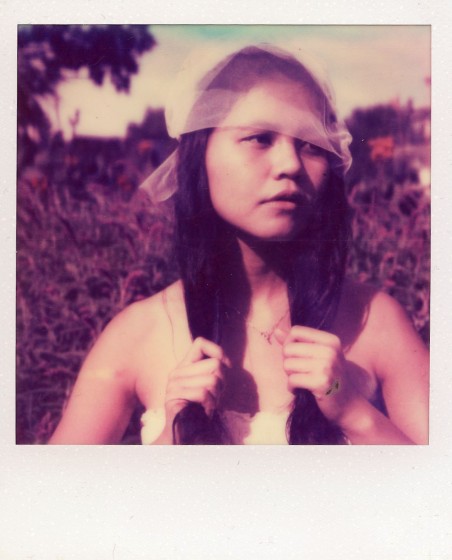

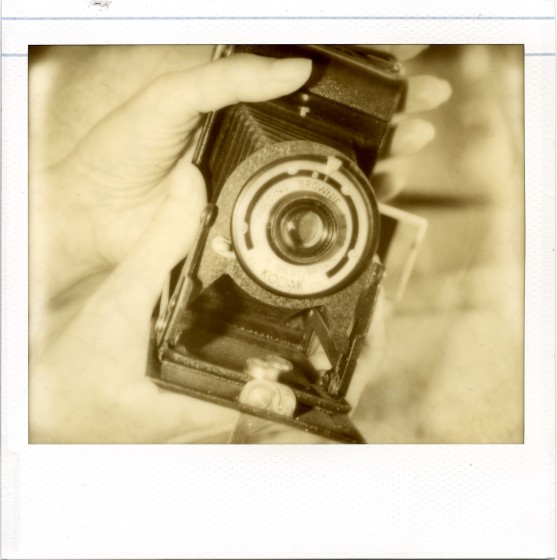

I was eight years old when I got my first Polaroid camera. I took pictures of everything and anything that proved even momentarily interesting. As I got older, I began taping the pictures to the walls and ceiling of my room. Artistic expression? I sure thought so. Nowadays, these photos remain in a box on the upper shelves of my closet in my parents home. Every once in a while I take the box down and look through the photos, occasionally with someone else.

The interesting commonalities between Andrew's story and my own hinge upon the dichotomous nature of tangible photos and scanned digital copies that exist on the web. The digital copies are immediately stored in archives with the photos of individuals from around the world. The excitement that used to come solely from receiving a tangible photo within minutes or seconds after pressing the shutter is now shared by the prospect of immortalizing the image on the web.

This is where the pictures branch out into two vastly different tracks--there are the photos that exist as tangible, physical entities and the digital images, which exist in cyberspace. "Paying attention to the specific physical qualities, the complex sensuality and materiality: how they look and feel, their shape and volume, weight and texture," helps illustrate how these images are rooted in...social and cultural contexts (Rose 219). Instant film photography has a very specific look and feel. There is the iconic white border that almost anyone would be able to identify as 'a Polaroid.' The fuzzy inconsistencies between light and color remind us of the truly fuzzy nature of memory, the degradation process that occurs over time. Keefe and Inch describe the process of making photographs as such, "Any photograph resembles a living organism in that it has a natural life span…there is nothing permanent about it" (1,2). This is arguably one of the fundamental reasons that instant film photography has been able to survive and re-emerge so vibrantly--these kinds of images satisfy the desire for instant gratification, yet appeal to the human truth that memory, the temporal recollection of events, is imperfect but nonetheless valuable and beautiful in its own way. It is perfect and flawed.

In contrast, the digital versions of instant photographs remain stagnant and unchanging. They can never be experienced in the same ways that tangible photos can. Yet, "online exhibitions," are not limited by some of the factors that the tangible photos are subject too, "[they] are aspatial, and can be accessed simultaneously by a number of users or 'virtual visitors,' from various networked locations across the world," (Silver 826)? This refers back to the mobility of images, and mobility, as aforementioned, looks at how images give up and claim new meanings when moved through different places, spaces, and time. The digital images remain in a medium that reaches across the globe while the tangible photos move, usually, less quickly and less far than their digital counterparts. This problematizes how we view images on the web. They are, in a sense, public domain-meaning anyone can see the photos, anyone can take them and use them. This raises ethical questions, but also highlights just how easy it has become for pictures to move in a modern world.

Images as Artifacts |

History |

The Impossible Project |

Let's Talk Discourse |