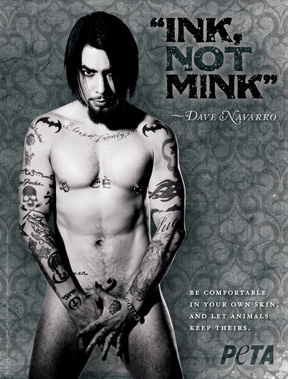

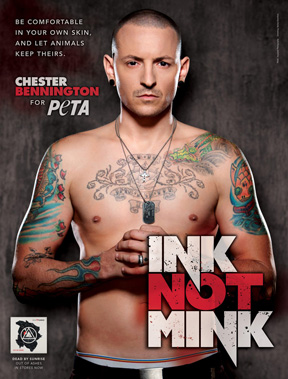

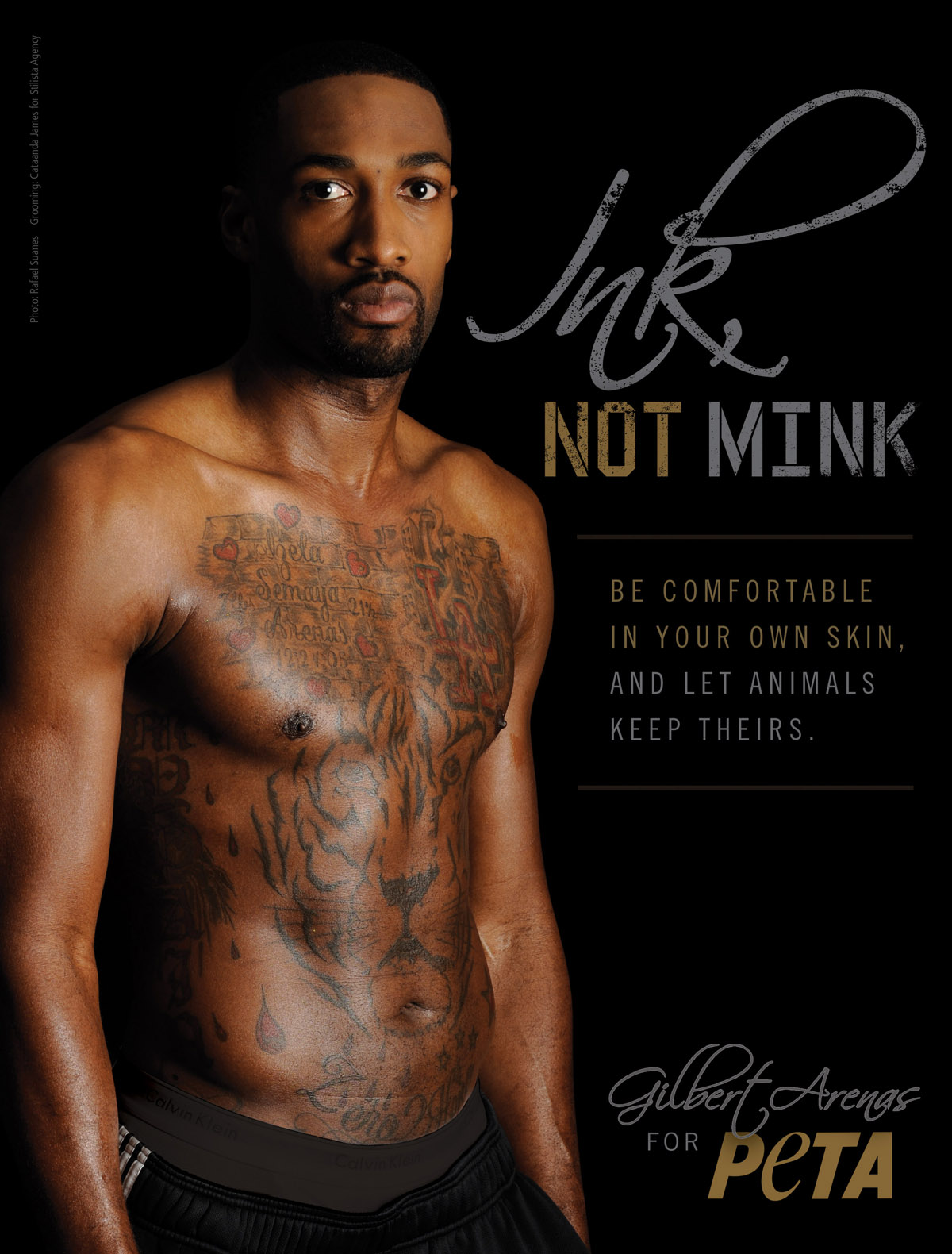

Ink, Not Mink Campaign

While the "I'd rather go naked that wear fur"

campaign primarily displays women's bodies, the "Ink, not Mink"

campaign focuses more on men and often, a racialized male body. Their

slogan for this campaign is "be comfortable in your own skin and let

animals keep theirs." Although there are many flaws in this

comparison and one could argue that you don't have to be comfortable

in your own skin to let animals keep theirs or go naked to avoid

wearing fur, I will instead focus on the implications of the images

and the bodies represented in them. This campaign, with its male

subjects, reaffirms dominant ideologies that are just as flawed as

their slogan.

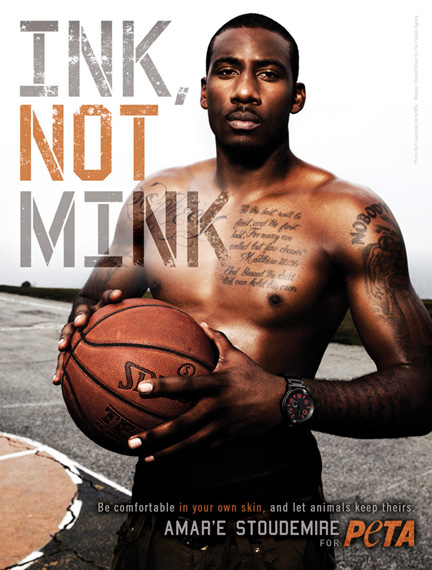

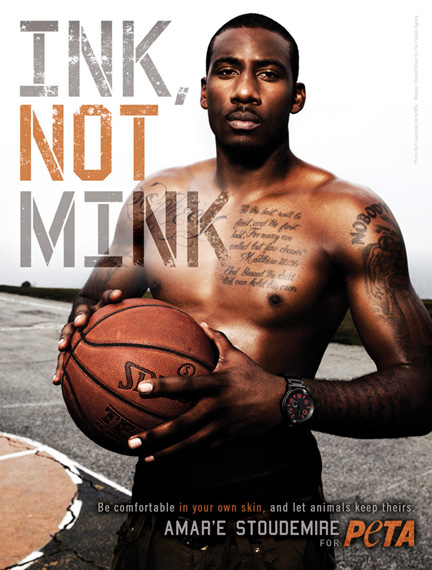

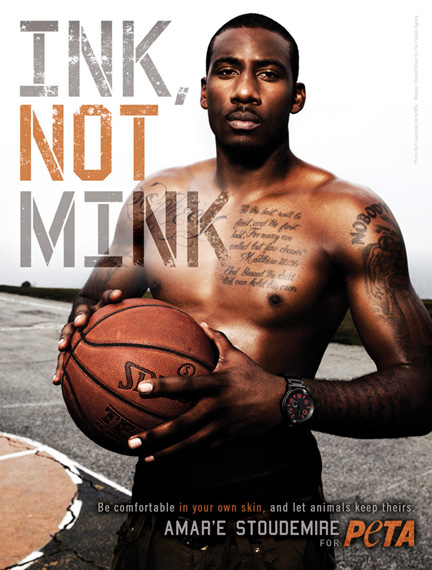

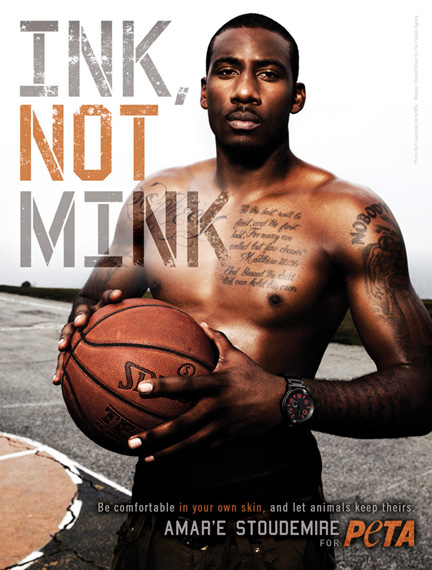

| The first ad from this campaign that

I will discuss features New York Nick's basketball player, Amar'e

Stoudemire shirtless, holding a basketball, and baring his tattooos.

Significantly, Amar'e is not completely naked as he is wearing shorts.

Because of this, his body is less on display than Karina Smirnoff's on

the previous page. Her body is on display in a sexualized manner but

Amar'e's is shown to display his tattoos and this is why we only see

his upper body. Thus the tattoos are the object and he himself is not

objectified as women are in other PETA ads. He is also looking

straight at the viewer in a way that asserts his power. According to

Jewitt and Oyama, his position as an athlete, which is clearly encoded

to the audience through the basketball in his hand, depicts another

kind of power, heterosexual power. Their research found that "sports

equipment and settings were used to signal competiveness between men

and as signifiers of their heterosexuality" (144). So Amar'e is both

being put on display as well as privileged in comparison to the not

shown referent of those who are not masculine and heterosexual. |

|

|

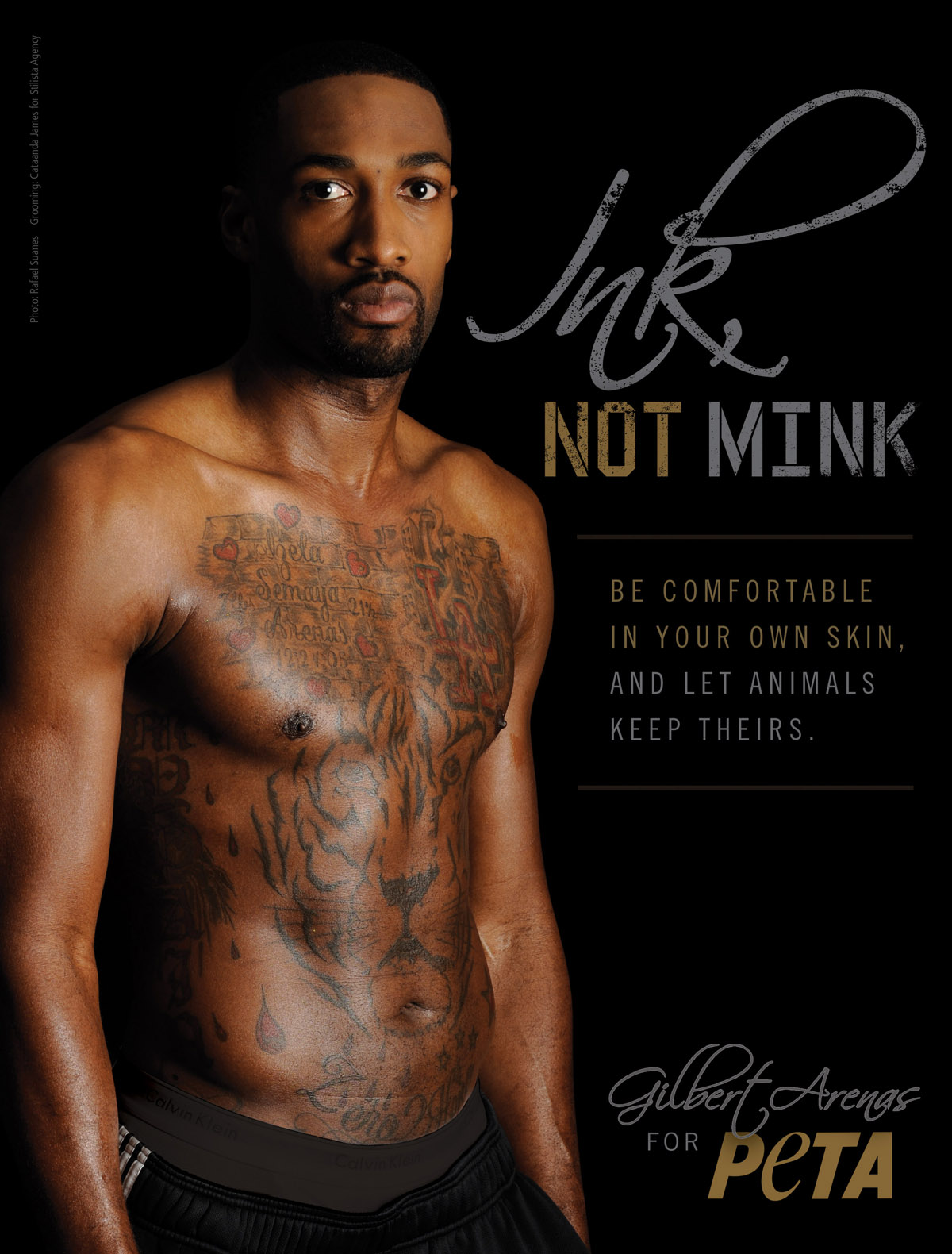

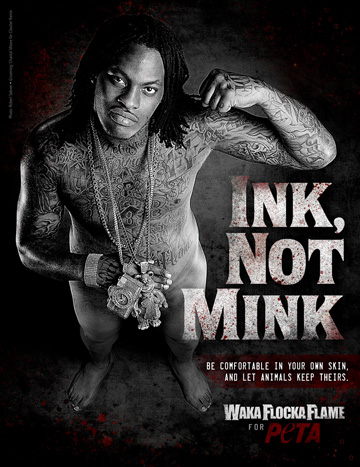

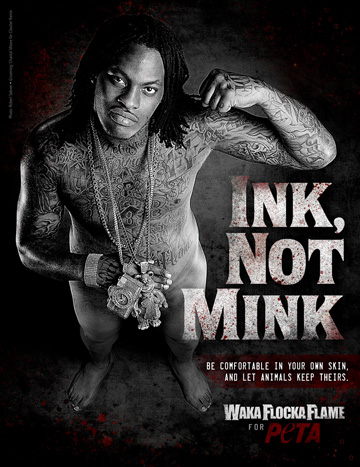

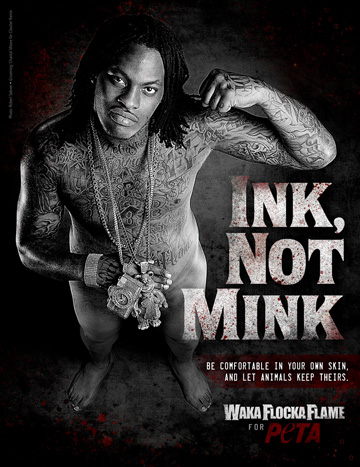

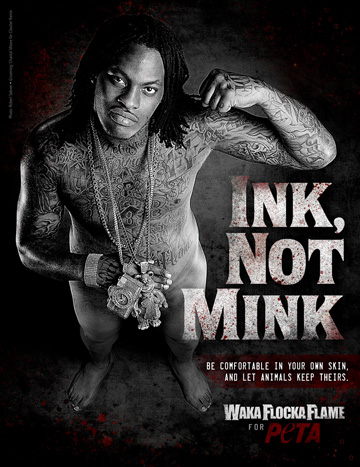

The second ad in this campaign features the rapper Waka Flocka

Flame completely naked. To illustrate his persona as a rapper, he is

pictured with large "bling" jewelry that acts as a phallic symbol by

covering the actual genitals. The point of view of the ad is slightly

above his eye level but the fact that he is looking up at the viewer

and making contact while also raising his arm in a way that could be

interpreted as either flexing his muscles or making a threatening fist

is his way of asserting his power. Because of this power, he is naked

but not objectified in the traditional feminized sense. The

positioning of his arm and fist can be anchored by the large, bold

"ink not mink" caption. This can draw a viewer to focus one of the

polysemic readings of the ad that Waka Flocka Flame is taking a stand

against fur and threatening opponents of his view.

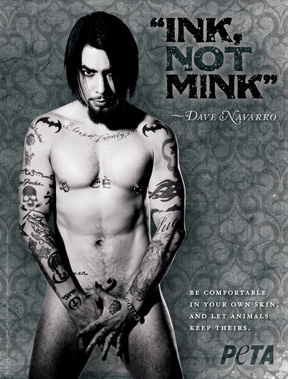

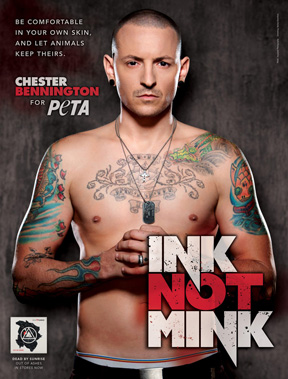

Although these two ads mark a trend away from the traditional nude

female ads, some of the underlying ideologies about race that I see

expressed in the campaign are bothersome. PETA only features

celebrities in their notorious nude or close to nude-ads and in PETA's

history, they have been primarily white and female. The "ink not mink"

ads are breaking trend by using primarily African American male

celebrities to spread their message. However, the only African

American men in this campaign are rappers or professional athletes.

This reinforces cultural misconceptions that these are the paths that

African American men can become famous. PETA doesn't challenge this

assumption by featuring an African American actor, jazz singer, etc.

|

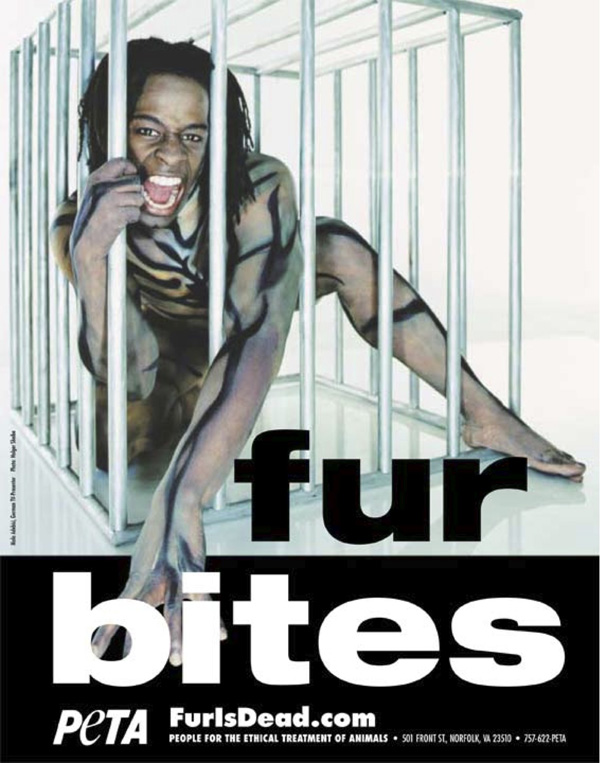

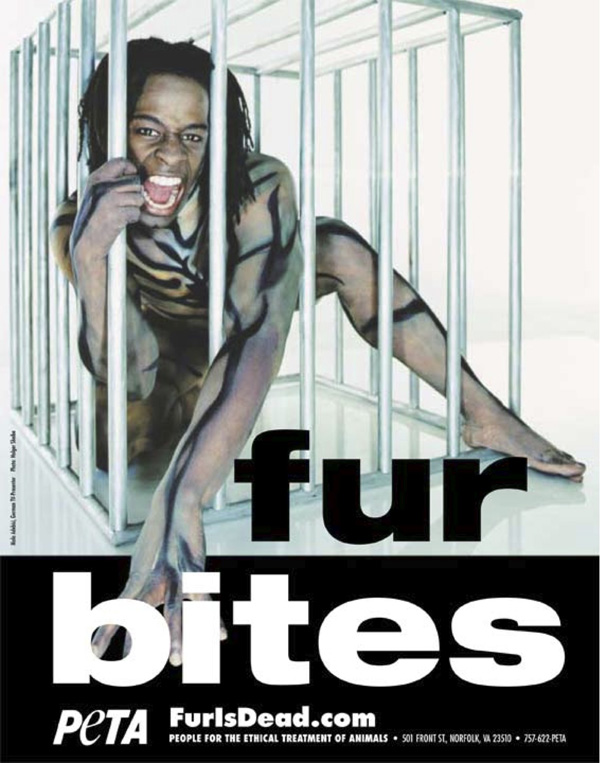

| Also, if we look at PETA ads of African American men

intertextually outside of the "Ink not Mink" campaign we see an even

more problematic representation. Particularly, we need to consider

these ads within the context of the ad on the right of an

African American as a caged animal sticking his face out to bite an

onlooker. Many of us know of, although it would appear PETA does not,

the lengthy history is which those in power in the Western world have

oppressed and "othered" those with less power, often being people of

African descent. The Image to the right of the man in the

cage characterized as an animal continues the painful history of

displaying and of often caging people of African descent that Coco

Fusco outlines. This history ranges from Columbus' capture of Native

peoples in 1493 to 19th century when "The Hottentot Venus" was

displayed for her body and had her genitals preserved at her death to

as late as 1992 when "a black woman midget is exhibited at the

Minnesota State Fair, billed as 'Tiny Teesha, the Island Princess'"

and arguably on to today (Fusco 41-43). The comparison of an African

American to a caged animal is ironic given the vegetarian ecofeminism

case for animal rights activism. Greta Gaard argues that this group

based their movement on "the conceptual linkages among sexism, racism,

and speciesism; on the recognition of flesh-eating as a form of

patriarchal domination; and on the basis of the culturally constructed

associations among women, animals, people of color, and nature" (127).

Given these conflicting views and actualizations, where does PETA

stand in regards to a progressive message? |  |

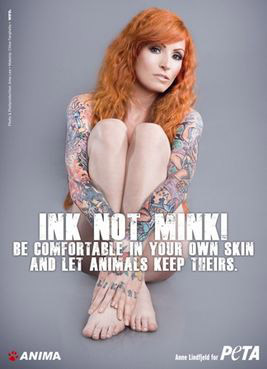

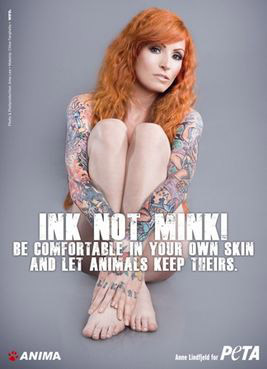

| The "Ink, Not Mink" slogan was also used in a

2009 protest in Sydney, Australia where tattooed model, Dani Lugosi,

stood in a street mall wearing nothing but a nude colored thong and

nipple pasties and holding an "Ink, Not Mink" sign. I argue that Dani

Lugosi is not objectified because she is actively engaging with

observers, even posing for a picture with one. The construction of

this protest in the physical space rather than as a print ad creates a

different dynamic for the presentation of a nude woman. First, she is

constructing her own performance. There isn't a group of people

coaching her on how to stand, what facial expressions to make, and

what angle to turn to hide her breasts like there would be at a photo

shoot for a PETA ad. She has agency over her body and she changes

stances, directions, and the positioning of her sign as she chooses.

She also isn't airbrushed like she would be in photographs in an ad

and although she is still on the thin side, she has a more realistic

looking body than Karina Smirnoff, Janice Dickinson, Pamela Anderson,

or the other celebrity PETA models. Since Dani is in the same

physical as space as her spectators, the effect of the male gaze is

lessened. If the male gaze is seated in voyerism, which distances and

objectifies the object, a human object/subject cannot be distanced in

the way that a print advertisement can (Rose 117). In this sense

models/protesters are play a more progressive subject rather than

their print advertisement counterparts that are more

objectified. |

Works Cited Fusco, Coco. "The

Other History of Intercultural Performance." English is Broken Here:

Notes on Cultural Fusion in the Americas. New York: The New Press,

1995. 37-64.

Gaard, Greta. "Vegetarian Ecofeminism: A Review Essay." Frontiers: A

Journal of Women Studies 23.3 (2002): 117-46. Print.

Jewitt, Carey and Rumiko Oyama, "Visual Meaning: a Social Semioric

Approach," in Theo van Leeuwen & Carey Jewitt (eds.), Handbook of

Visual Analysis (London: Sage, 2001), pp. 134-156.

Rose, Gillian. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the

Interpretation of Visual Materials. 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications,

2007. Print.