|

|  |  |  |  |

|

|  |  |  |  |

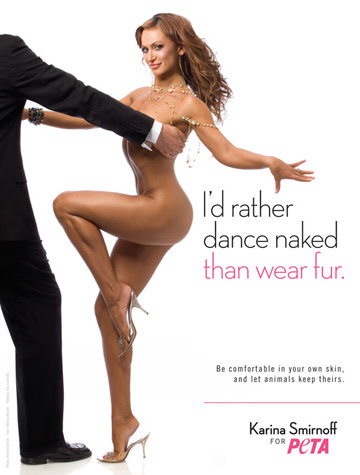

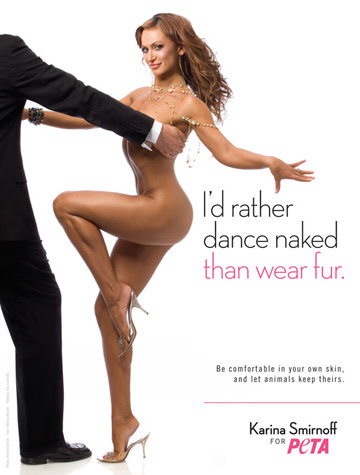

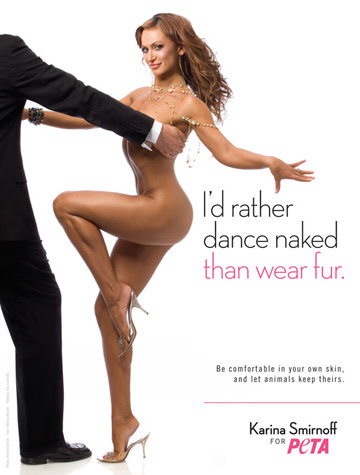

| This ad featuring Karina Smirnoff is captioned "I'd

rather dance naked than wear fur," a play on the usual title of "I'd

rather go naked." Smirnoff is a professional dancer who has appeared

on several seasons of Dancing with the Stars. The ad shows Karina

dressed in high heels, makeup, and jewelry but nothing else as she

dances with a faceless half body of a man in a tuxedo. Karina looks

towards the viewer of the ad but her body is facing towards her dance

partner who we know can see what we can't: everything. Although the

pair is supposed to be dancing, it also looks like he is moving, maybe

even dragging her in his direction and off the page. According to

Stankiewicz and Rosselli, Karina can be interpreted to be an

objectified body because her sexuality is being used not to sell a

product but to sell the message of animal rights, specifically

abstaining from fur. She also fits the profile of object rather than

subject because according to their criteria because she gives the

camera a suggestive smirk and her body position is exaggerated to

place emphasis on her legs, buttocks, and lower abdomen (583). Stankiewicz and Rosselli argue that the use of women as sexual objects in print magazine advertisements is significant because "there is evidence that exposure to sexually objectifying advertisements produces anti-woman attitudes...[and] attitude[s] that women are valuable only as objects of men's desire, that real mean are always sexually aggressive" (581). Aggression is a topic that I will later address in the context of the "Ink Not Mink" campaign but it is important to consider the interpretation of aggression in this ad as well. It is significant that there is the faceless but clothed body of a man who is asserting power of Karina's body by moving it/moving with it and also by hiding her breasts from the audience, establishing that as a part of her that he can see but that we cannot see.

| |

It is important to remember that this and all ads produce a polysemy of meanings and under some analysis, Karina's ad could be read as more liberating that oppressive. Joan Forbes argues that to some, with women's "increased sexual choice, expression, and freedom" there is "this 'progressive' tendency to associate sexuality with individual 'liberation'" (179). Some could argue that Karina's sexualized ad is an assertion of female sexual power. We also tend to assume that sexualized images of women are only seen through a voyeuristic male gaze that is inherently objectifying to women (Rose 121-122). Forbes reworks this tradition approach to voyerism to suggest that since there is an unavoidable "female spectatorship" that will view the ad, "'female gaze'" is created where women possess "the possibilities for female desire and pleasure within heterosexuality" (177).

| The gendered

positions present in Karina Smirnoff's ad are reversed in a 2007 "I'd

rather go naked than wear fur" protest featuring Janice Dickinson.

Photographic images of the protest that have circulated online show

Dickinson slightly dressed in what appears to be sleepwear: a white

tank top and panties. As a celebrity and supermodel, Dickinson became

the face of the protest but she was surrounded young men and women

also protesting with the same PETA signs. The other women all appear

to be much younger than Janice and are dressed slightly more

revealingly in bras. But it is the young men who bare all to prove

that they would "rather go naked than wear fur." A particularly

eye-catching image from the protest shows a young male model

completely naked and cupping his genitals with his right hand while

Janice places her hand over that hand. In this image, Janice Dickinson

is asserting power over the man both by her clothed status to his

unclothed status and her physical interaction with him. By Stankiewicz

and Rosselli's classification, Dickinson is acting as an aggressor

because she is "dominant over a man in a sexual act" through her

physical contact with his body and also her clothed status to his nude

status (584). This may seem surprising given the social construction of gender that we are used to. Still, Dickinson has more social power than the man because she is older and a very wealthy supermodel and he is young and a model at her agency. A woman of Janice Dickinson's status can say "I'd rather go naked than wear fur" without really going naked while her male comrades cannot. Although this breaks gender norms, it still reinforces other power hierarchies perpetuating inequality. |

|

Works Cited

Deckha, Maneesha. "Disturbing Images: Peta and the Feminist Ethics of Animal Advocacy." Ethics & the Environment 13.2 (2008): 35-76. Print.

Forbes, Joan S. "Disciplining Women in Contemporary Discourses of Sexuality." Journal of Gender Studies 5.2 (1996): 177-89. Print.

Pace, Lesli. "Image Events and PETA's Anti Fur Campaign." Women and Language 28.2 (2005): 33-41. Print.

Stankiewicz, Julie M., and Francine Rosselli. "Women as Sex Objects and Victims in Print Advertisements." Sex Roles 58.7-8 (2008): 579-89. Print.

| [Previous] | [Home] | [Next] |