The green RV seems to be a point of pride with Roadtrip Nation. It is featured in many of their images and descriptions, seemingly serving to represent their entire organization. In fact, it does this literally when Roadtrip Nation brings it to visit college campuses to recruit potential roadtrippers. It was the green RV that first caught my attention about the organization. The massive thing appeared on campus, brightly colored and decorated, and it was impossible to miss. After speaking to the staff about what Roadtrip Nation did, I was taken on a tour of the RV, necessarily brief because of its limited space. The roadtrippers and crew members live together in the RV for the entirety of their 6-week journey, taking turns driving it.

On the website, there is a page devoted to them inviting readers to "Meet the RVs," describing them as "family members" (roadtripnation.com). It is important to recognize that as central figures in the images online and in the documentary, the RVs transport people in more ways than one. Julian Smith, in his article "Transports of Delight: The Image of the Automobile in Early Films," theorizes that "both motion pictures and automobiles are forms of transportation," and not even necessarily in separate ways (Smith 59). Smith's analysis has to do with films produced in the early days of the car, but I find it applicable here because of the nostalgic image of the road that Roadtrip Nation invokes. In this case, the RVs clearly transport the roadtrippers once they set off for their travel experience, but there are other transportations going on when a person looks at the images online or watches the show produced at the end of the journey, even when the RV visits college campuses and carries away college students with the idea of travelling with strangers for a summer. I think this way of framing the purpose of the RVs is important to keep in mind.

The RVs take on personality through the way the website introduces each of them. Each has a name, such as The Legend, Norm, Spud, and Junior. Each is listed along with its number of road trips and its mileage, bringing the focus again back to the road. Monaco is clearly the winner, with 7 road trips and over 200,000 miles under her belt (they are each assigned a gender as well). Moreover, each image introducing the values of the website, discussed previously, include images of the RVs. The images have a summer-camp feel to them: the RVs are covered in signatures, people are popping out of every window, and the interior is complete with slightly grungy couches. In fact, the organization hardly seems as though it would be able to exist with any other type of vehicle. For the purpose of this analysis, I will look at the ways in which the RV is shown to representative of all of Roadtrip Nation's values in the images they use online.

| First, I will take on the image that pops up accompanying the "History" page. Each image on these pages is composed of many smaller images, leading the eye in many directions at once. On the history page, the images fall into three simple themes of the RV on the road, the roadtrippers, and the inside of the RV, which were apparently chosen to work cohesively to represent the history of the organization. The images of the RV on the road vary in style - there is a line of RVs in a crowded city, an RV artfully (but uselessly) in the middle of the road not moving, and a final one of the RV on a long, winding road unmarked by signage or construction. |  |

|

Important here is Karl Raitz' point that "Roads are as much social as physical constructions" (Raitz 364). Raitz is getting at the idea that a great deal of social, political, and economic factors go into constructing a road, which is definitely true. Also, though, the idea of roads as social constructions necessarily means that roads continue to communicate those social factors once it is built. In the case of this image, different positions of the RV placed next to the people who use the RV essentially communicate a vision that was partially already there in the structure of the road but which is encouraged by Roadtrip Nation's organization of images as well. Therefore, when I look at the image representing "History," I understand what I am supposed to see: motion is represented despite the stillness of the photos, and a sense of the different environments that build a travel experience. |

| A different composition of photographs was chosen to head up the page for "The Team." This image is much more

focused on people than the first. There are several groups of people working, one of several team members posed in

front of the green RV, and one particularly interesting one of 7 or 8 people pushing the RV down the road. Though

the RV is not as prominent in this photoset, I think it is particularly relevant to the point of this page. After

all, Roadtrip Nation chooses three people, often strangers, to live together in a confined space for 6 weeks. Clearly,

teamwork is an important skill. It is interesting to me to see how this theme interacts with modern conceptions of

travel.

Contrasting with this method of travel is the dominant thought for the last several decades about what it means to have a car: "While the private car seems an inevitable outcome of a capitalistic, individualistic modern society, much work has gone into the process of naturalizing a dominant notion of automobility on drivers' horizons. Through art, literature, popular music and brand advertising, the car has long been associated with seductive forms of identity, and societies have been built around a hegemonic culture of car ownership and driving as the pre-eminent, modern mode of self-expression" (M/C Journal). With the threat of global warming and other environmental concerns, though, "car sharing provides a challenge to the dominant consumerist model of the privately owned car that has sustained capitalist structures for at least the last 50 years" ("Cars, Climates, and Subjectivity"). The green RV buys into this not only in the fact that it forces people to share, but Roadtrip Nation also makes sure to inform readers that the green RVs are environmentally friendly. |

|

|

More than anything else, though, I think the idea of teamwork and the image they chose to represent it hope to challenge the consumerist model discussed above. The images do not show a staff strict on making money. Instead, the people are relaxed and enjoying themselves, and always working together rather than independently as dominant models would have it. This extends to all aspects of the green RV experience, inside and out, as evidenced by the photos. Pentti Haddington et al. discuss this in "Meaning in motion: Sharing the car, sharing the drive." In their article, it is stated that "Car occupants are made visible as participants engaged in practices of social action and oriented to events of the immediate and constantly evolving driving context. They are situated actors who use their immediate interactional and semiotic context to create understandings for experiencing and accomplishing mobility" (Haddington et al. 106-7). As participants in the road trip and as actors in the documentary of sorts, these sorts of social interactions could go a number of ways. Through their organization of images on their Team page, Roadtrip Nation would have us believe it goes smoothly and with happiness and enthusiasm at all times. It is, after all, in their best interests. |

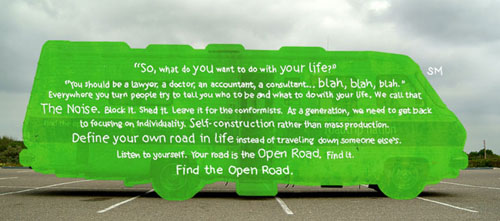

The last image of this group I want to specifically identify is that which is found on their "Manifesto" page. Pictured is a bright green outline shaped like the RV, within which a quote resides stating their manifesto as an entity. It begins with "So, what do you want to do with your life?" and takes it to the end with "Find the Open Road." As a manifesto, it is perfect in the way it defines Roadtrip Nation's purpose and calls for participation from the reader. More interesting than simply the message, though, is the medium in which it is delivered. Their manifesto is not a document, but one image. Upon that one image is summoned up the character of the green RV. It also works in the combination of styles present in other graphics. I would hold that it communicates a bit more than simply what is written in white letters.

Some of the important points of analysis for this image are the real aspects of the photograph, i.e. the pavement of the parking lot and the trees in the distance. Shane Gunster, in writing on SUV culture, makes an interesting comment related to this: "Invoking nature as the endpoint of vehicular travel affirms one of automobility's most precious and fiercely guarded illusions, namely, that spatial mobility offers access to places, experiences, and events that are fundamentally different from everyday life, that one can escape to somewhere other than where one is now" (Gunster 5). Though Gunster's comment was made with regard to SUVs, I would make the argument that the same process is going on here. A parking lot (in the foreground) is the start of a journey, while the trees in the background represent the goal, the path to finding "the Open Road."

This idea is incredibly nostalgic. As Stine and Tarr note in their article, "The automobile is the transportation technology most associated with environmental degradation" (Stine and Tarr 616). However, this point of view is largely absent from Roadtrip Nation's rhetoric or in the larger discourse or nostalgia about road travel as a whole. Skidmore's historical approach to understanding the importance of the road reveals some of the reasons behind this. Skidmore notes that by the early 20th century, "The country's love affair with the automobile was set to burst into bloom" (Skidmore 167). He notes, though, that it required quite a change in understanding with regard to the use of empty spaces. The individuality and freedom attainable only by driving is something that was constructed much as roads were, as Skidmore brings in Peter Norton to discuss: "It required pressure, subtle and otherwise, from special interest groups working through governments to claim the streets exclusively for the auto and to redefine them so that they no longer were 'public spaces,' where children played and pedestrians wandered (Norton)" (Skidmore 167). The process was clearly successful, as we hardly think of roads today as public spaces where people can be.

I feel that the results of this shift in thinking are highly present in the Manifesto image: the pavement is empty of people, the space just waiting to accommodate the movement of the travellers. The road is something that is represented as belonging to the green RV. It has no challengers or opponents, because the road is empty otherwise. Leaving the focus entirely on the green RV and the empty road in this photo and many others is part of what constructs the movement (literal and figurative) of Roadtrip Nation.

|

Home |  |

Works Cited:

"Cars, Climates and Subjectivity: Car Sharing and Resisting Hegemonic Automobile Culture?" M/C Journal 12.4 (2009): 1-12. Print.

Haddington, Pentti; Maurice Nevile; and Tuna Keisanen. "Meaning in motion: Sharing the car, sharing the drive." Semiotica 191.1 (2012): 101-116. Print.

Gunster, Shane. "'You Belong Outside': Advertising, Nature, and the SUV." Ethics and the Environment 9.2 (2004): 4-32. Print.

Raitz, Karl. "American Roads, Roadside America." Geographical Review 88.3 (July 1998): 363-387. Print.

Roadtripnation.com. Roadtrip Nation, 2013. Web. 23 Apr 2013.

Skidmore, Max. "Restless Americans: The Significance of Movement in American History." Journal of American Culture 34.2 (2011): 161-174. Print.

Stine, Jeffrey K. and Joel A. Tarr. "At the Intersection of Histories: Technology and the Environment." Technology and Culture 39.4 (1998): 601-640. Print.