|

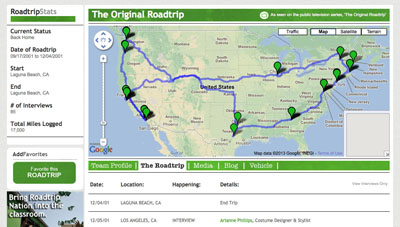

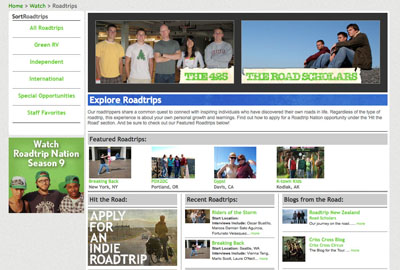

One of the most fascinating parts of the Roadtrip Nation website is the page where they detail each of their road

trips from the past several years. Each road trip receives a profile page, complete with information on and pictures

of the roadtrippers, an interactive map, and detailed itinerary. On the same page can be found information about how

to apply, blogs from the road, and their international work. What I am interested in with regard to this page is the

way travel photos and maps are turned into symbols of something greater than themselves. Everything that Roadtrip

Nation wants to be or wants to represent, such as independence, fulfillment, and freedom, are shown in the road trip

profiles. This is achieved through their invocation of classic travel ideals through this modern medium. The appeal

to nostalgia has been present in many other areas of their website, but I find that it is perhaps strongest on these

pages, where the concrete artifacts from the road trips are reproduced online.

These artifacts, i.e. the interactive map, itineraries, and travel photographs, render the journey accessible in a way old road trips are not. Because of the technology we have now, visitors to the website are users rather than merely viewers, emphasized again by the imperative verbs used as links to the pages of the site. Rose says that the term user has become "a better way of capturing the multiple ways and levels in which people engage" with a medium (Rose 273). While Rose specifically discusses the relevance of this term to television audiences, I would advocate that the internet has created more users than television ever has. In this case, a Roadtrip Nation user might choose to recreate the provided road trips, attempt to get in contact with the interviewees, or simply follow and comment on the road trip's blog. Considering these options never would have been available in a world of only audiences and fans (to use Rose's terms), we are clearly dealing with new ways of interaction. |

|

|

Raymond Williams' famous essay on "Mobile Privatization" can shed some light on how these worlds of technology and nostalgia

interact. Williams details how we have turned the world into many small compartment which feel independent: "Looked at from

right outside, the traffic flows and their regulation are clearly an order of a determined kind, yet what is experienced

inside them - in the conditioned atmosphere and internal music of this windowed shell - is movement, choice of direction,

the pursuit of self-determined private purposes... And if all this is seen from outside as in deep ways determined, or in

some sweeping glance as dehumanized, that is not at all how it feels inside the shell, with people you want to be with,

going where you want to go" (Williams 129). I feel as though Roadtrip Nation seeks to create and inhabit this inner shell,

represented here by their fleet of green RVs and their photographs published online, perpetuating nostalgic ideas about

how travel can change lives and lead people down the path to true happiness.

However, what consumers of Roadtrip Nation are really buying into is much more regulated than it seems. It operates on capitalist principles, directly oppositional to their message of escaping traditional expectations and finding one's own definition of success. Of consumers, Williams says: "Sovereign? That raises a problem, but while the production lines flow and the shopping trolleys are ready to carry the goods away, there is this new, powerful social identity, which is readily and even eagerly adopted" (Williams 128-9). Roadtrip Nation wants each of their viewers/users/consumers to believe in their own sovereignty; the problem is that Roadtrip Nation's manipulation of nostalgia through a technological medium seeks to take this very sovereignty away. |

|

Jeffrey Stine and Joel Tarr, in their article "At the Intersection of Histories: Technology and the Environment," attempt to

theorize interactions like those that occur on the page which includes the maps and photographs. They say: "Landscape studies

and historical geography, which typically embrace considerations of natural resources, have also examined the connections

between technology and the environment. In this respect, the environment often involves geographical space and overarching

spacial relations, while technology often includes various means to define and/or overcome those spaces" (Stine and Tarr 633).

This website, through its map and images, seeks to do exactly that.

To make the user feel closer to the journey itself is to make them more invested (monetarily or otherwise) in the mission of Roadtrip Nation. The way to make them feel closer is to put the trips into their hands or in front of their eyes. Giving users maps to click through, lists of those interviewed to read, and images of the roadtrippers is to essentially give them the keys. The wheel is in their hands and their own use of these materials is in their hands. I enjoyed Stine and Tarr's use of the term "natural resources" because it is in line with Roadtrip Nation's focus away from the consumerist or 'fake' parts of our country. They seek 'authenticity,' which in their terminology seems to mean untouched. When the landscape the roadtrippers encounter is new, it has the romantic appeal to both the travellers and the viewers that drives road-narrative nostalgia. Since their journey is meant to help them discover their inner selves, it makes sense that they would seek land that is newly 'discovered' as well. Anne Marit Waade provides another way to understand these images, particularly those showing the roadtrippers and the places they visit. In her article titled "Imagine Paradise in Ads: Imagination and Visual Matrices in Tourism and Consumer Culture," she explores the use of travel images to invoke desire in their viewers. What I appreciate about this article is that it helps to reveal the hypocrisy inherent in Roadtrip Nation's stated goals. They ostensibly seek to separate themselves from consumer culture by encouraging their roadtrippers and viewers to "find the open road" away from stereotypical definitions of success, which usually means having a great deal of money. Instead of money, they want people to find true fulfillment in the romantic sense, whatever that may be for them. However, they exist through capitalist and consumerist means by selling their DVDs the same way they sell their ideology. Waade states that: |

|

|

"The touristic image of exotic sites, landscapes and experiences is not limited to tourism marketing and tourism literature.

Along with the expansion of tourism as an industry and a cultural praxis, tourist images, tourist destinations and tourist

experiences are used as aesthetic strategies in, for instance, literature, television series, marketing and locations in

films and computer games... Paradise as a cultural and historical concept has some specific visual features and reflects

ideas of a perfect way of living, including the essence of a good life." (Waade 15)

Roadtrip Nation is not quite the same, in that it does not use exotic images to create this atmosphere, but it does seem to have similar goals to the travel ads and other sources Waade cites. Most of their road trips occur in the United States; many of the places visited are familiar to viewers and roadtrippers alike. This, though, only serves to try to assert that these places we are familiar with have a magic all their own that must be brought back to our understanding of our country. It almost has a nationalist sort of flavor: images of our own country are used to impassion viewers and appreciation of these places close to home through travel is said to improve our lives and give us greater happiness. |

However, as Waade emphasizes, rather than simply emphasizing happiness as an end result, these images serve capitalist and consumerist ideals. Waade describes this phenomenon as "imaginative consumption": "Imaginative consumption differs from physical, concrete consumption (e.g. buying a pair of shoes) and mediated consumption (e.g. seeing a person buying a pair of shoes in a TV ad). Imaginative consumption includes all kinds of consumption that take place in a person’s mind, all his/her fantasies, daydreams and plans about, for instance, buying a pair of shoes, including how s/he might look wearing the shoes, how they feel to put on, to walk in, to show off and so on" (Waade 16). This is precisely what Roadtrip Nation does with their travel images and the maps: one is meant to see the map and imagine themselves driving it, or see the images of the roadtrippers with the green RV and imagining themselves living in it for the summer.

The show they produce is meant to do the same: by revealing every aspect of what it is to be a Roadtrip Nation roadtripper, they make it easier for viewers to put themselves in that place. Once their viewers imagine themselves there, they are much more likely to buy the DVDs or even apply for one of the road trips, which perpetuates the existence of the company. In this case, the imaginative consumption begets physical consumption, both of which support Roadtrip Nation. They have learned to use already existing nostalgic notions about travel, particularly road travel, in order to encourage this line of thinking. The travel photographs and maps add the component of technology to these preconceived ideas, making Roadtrip Nation powerful in their rhetoric and broad in their reach.

|

Home |  |

Works Cited:

Roadtripnation.com. Roadtrip Nation, 2013. Web. 23 Apr 2013.

Rose, Gillian. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. 2nd Ed. Sage Publications: Washington DC, 2007. Print.

Stine, Jeffrey K. and Joel A. Tarr. "At the Intersection of Histories: Technology and the Environment." Technology and Culture 39.4 (1998): 601-640. Print.

Waade, Anne Marit. "Imagine Paradise in Ads: Imagination and Visual Matrices in Tourism and Consumer Culture." NORDICOM Review 31.1 (2010): 15-33. Print.

Williams, Raymond. "Mobile Privatization." Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. Paul Du Gay, Stuart Hall, Linda Janes, Hugh Mackay, and Keith Negus, ed. London: Open University/Sage, 1997. 128-129. Print.