The Hegemonic Myths and Ideologies Perpetuated by Mattel

|

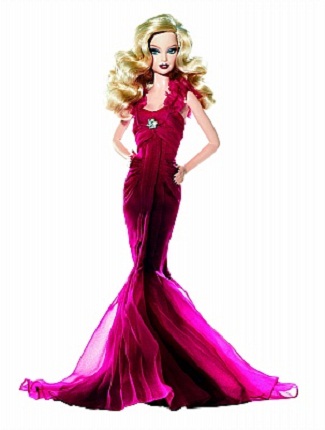

Mattel is often critiqued by feminist scholars who claim that Barbie exemplifies hegemonic beauty ideals and reinforces patriarchy, the normalization of heterosexuality and white imperialism within Western society. These claims are not based solely on the scholar's opinions, but often arise from ethnographic research regarding Barbie consumers. In her book Barbie Culture, Mary E. Rogers recalls an interview with a student from Midwest State University, in which the student told a story of her sister cutting off her Barbie's hair and the fact that they 'demoted it to a 'Ken' Barbie-doll, probably because it no longer fit the perfect dream-girl image.' Rogers emphasizes the students words, "Perfect. Dream girl. Image. [Asserting that] [t]hese are terms of many girls' engagement with Barbie. These terms ensure they can never measure up" (13). In Rogers' encounters with women and girls alike, she found that adjectives such as "beautiful" and "ideal" were used often. Simply put, consumers are entwined in what Naomi Wolf calls the "beauty myth," which "tells a story: The quality of 'beauty' objectively and universally exists. Women must want to embody it and men must want to possess women who embody it" (Wolf 12). In her book Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials, Gillian Rose suggests that a myth is a form of ideology that makes us forget things are made, and instead naturalizes the way things are (96-97). Barbie has many myths surrounding her that naturalize hegemonic ideals in society. One recent study "found that the media begins to have a negative impact on body image for girls as young as nine years of age." (Weiskamp 5). While there are many images of beautiful women in the media that may affect young girls, having a tangible and beautiful object that resembles a woman may be even more harmful. The way in which Barbie perpetuates the "beauty myth," is by making her viewers, and especially consumers, believe that her physique is the ideal physique and her extreme feminine beauty is natural, and because of this myth women should be beautiful, and that men should want women who are attractive. A man in his forties whom Rogers interviewed regarding Barbie's beauty responded, "'Perfect hair. Shapely legs. Faultless breasts. An hourglass torso. For many years this was how I perceived what an ideal woman was supposed to look like. This spurious notion was implanted in my head--at an early age--when I got my first glimpse of a fully unclothed Barbie doll'" (17). The occurrence he describes is an example of scopophilia, a Freudian term that refers to the pleasure in looking, a drive which he claims all children are born with (Rose 107). This man, as a boy and for years after, idolized Barbie's figure and believed that women were 'supposed to look like' her. As Naomi Wolf points out, "The beauty myth is not about women at all. It is about men's institutions and institutional power." (13). This boy bought into the myth, as many individuals do because of the unrealistic and persuasive images of "beautiful" women that circulate in all forms of media, including the toy industry. Though the claim is refuted by Mattel, many believe that "Barbie was modeled after Bild Lili, a German postwar prostitute doll for adult men. [It is also suggested that] the doll was expressly modeled on a Hollywood ideal of beauty. Either way, Barbie is an object of the male gaze." (Cannon 4). Men are not the only scopophilic lookers at Barbie, however. The fact that women so often refer to Barbie as 'beautiful' and 'ideal,' shows that she appeals to their aesthetic senses. As exemplified by the man's first encounter with Barbie as a child, we see children experience scopophilia, and may not be as ashamed of it because they have not yet been fully versed on "acceptable behavior" in society. Rogers used open-ended individual interviews to study students at a middle-school where students are predominantly African-American and come from low-income households asked them about their feelings regarding Barbie.

Mattel's doll is also seen as problematic because she so adamantly adheres to gender norms. Some defenders of Barbie, Mattel especially, dispute these claims and call her 'empowering' for young girls. They use her many professions as evidence that she is presented as a woman who can do anything, even jobs which are traditionally considered to be men's positions, such as a police officer, doctor, veterinarian, etc. Conversely, as Rogers claims, she possesses "emphatic femininity," which she defines as taking "feminine appearances and demeanor to unsustainable extremes." (14.) She is always presented as feminine, "Nothing about Barbie ever looks masculine, even when she is on the police force" (Rogers 14). This fact emphasizes the gender binary that is an American ideology, meaning that Barbie, as impressive as her resume may be, definitely adheres to the normalized performance of gender. In American society we often do not differentiate between sex and gender, males are supposed to be masculine, and females are meant to be feminine, and through Barbie's performance of gender, Mattel is reinforcing prominent ideologies.

|