A Visual Cultural Study of Snapshot Photography, Landscape, and Tourism in the Contemporary American West

|

A Visual Cultural Study of Snapshot Photography, Landscape, and Tourism in the Contemporary American West |

|

Space is a medium through which the imaginary relation between Self and Other is performed.

---Gillian Rose

This is an interdisciplinary cultural study of the signs that tourists encounter at the ground level on roadways in the western national parks. In using multiple interventions into the ways that these signs mediate encounters between people and the land, between "nature" and "culture," and between physical space and imagined place, I explore some of the ways that physical signs inscribe and activate more general cultural and ideological discourses about the relationship between nature and culture into the topographies of the National Parks of the American West. The narrative I perform here is meant not only as an expression of my personal experience but as an allegory that attaches the fabric of abstract theoretical speech to a frame of embodied experience of a specific place in a specific time.

In The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies, John Urry argues that "Tourism results from a basic binary division between the ordinary/everyday and the extraordinary [which] necessarily involves daydreaming and anticipation of new or different experiences from those normally encountered in daily life." This is especially apparent in the U.S. National Parks, and within them, the western national parks. Since Yellowstone was established as the first National Park in 1872, the western national parks have played a particular symbolic role in American culture as the Other of culture. The underlying principle behind this symbolism is that the "natural" national parks are different from and (more importantly) should be maintained in contrast to culture--to "artificial" modern urban America.

As a 1973 Park Service pamphlet celebrating the centennial of the national park idea phrased it, "National parks today are in effect islands of (near) naturalness in a sea of civilized, man-manipulated landscape. . . . [C]are should be exercised to preclude the adverse and detracting influence of the modern, technological world." Because national parks are defined against the everyday social and cultural environment that most Americans live in, many Americans turn to the national park "wilderness" landscapes for respite from their everyday social world when they go on vacation. Cultural geographer Linda Graber argues that this attitude is especially pronounced among "wilderness purists," who consider wilderness "sacred space" that must be protected from degradation by the secular in much the same way that believers protect churches from "inappropriate" activities: "Purists seek a Wholly Other environment from their daily surroundings and oppose the penetration of reminders of the ordinary world into wilderness." But whether they are wilderness purists or industrial tourists (or any others in between, for that matter), visitors who come to the parks in search of the Other of contemporary American culture will find that the culture they had hoped to leave at home is inscribed into the parks as well.

Every space has a history--even places such as national parks that seem to be natural--and every space has a history that is simultaneously physical and discursive--a history that is inscribed not only into material landforms and the built environment but also into the minds and bodies of its inhabitants. This is because social relations are constructed and negotiated spatially and are embedded in the spatial organization of places.

What makes national parks interesting for the analyst of postmodern tourist culture is that because they are publicly owned and therefore all visitors must share the same finite space, national parks are charged with accommodating several kinds of visitation with correspondingly different spatial practices that are often in conflict with one another. What I want to do today is discuss the ways that these discourses are activated in the parks to explore the ways that tourists encounter marked territory in the parks but also to explore the process of marking new territory in the field.

Because we treat western national parks as "islands of wilderness" surrounded by "encroaching cultural landscapes," things like roads, signs, buildings, and even people look different in the national parks than they do elsewhere in America. The function of these signs, placards, official guides, and maps is important. The Visitor Centers and the "official" park guides and maps are meant to highlight, preview, and frame the marked sites within the park. When they design road signs, boundary signs, scenic overlooks, etc., National Park Service interpretive staff members act as "cultural intermediaries" who articulate a set of cultural meanings and practices, inscribing the land with signs that reflect not only Park Service policy, aesthetics, cultures, etc., but also more general cultural signifying practices. Exhibits at Visitor Centers for instance, display knowledge that is supposed to "interpret" the park as a whole for visitors and help them learn how to interpret it for themselves as they participate in the process of "reading" space.

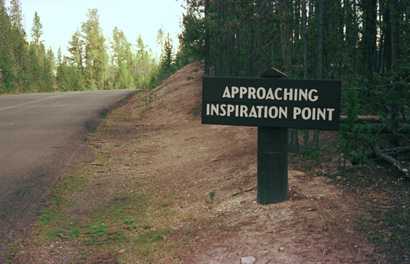

The signs that visitors encounter along the roads and at scenic overlooks within national parks serve a slightly different function: they mark the territory within and at the site. From the first moment a visitor crosses the boundary into a park, the signs begin marking difference. Beginning with the boundary signs made of stone and wood that identify the border crossing and extending to signs pointing to some things and not to others, park service signs authorize certain spatial practices and not others.

• Signs along the road direct visitors to stop, look, and photograph...

• They mark as significant things like "Big Cedar Trees"...

• Others promise states of being, such as this sign in Yellowstone...

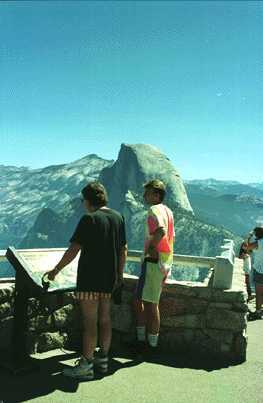

• Signs at scenic overlooks identify features in the field of vision--showing visitors what to look at and what to make of what they are looking at...

• Others demand compliance with official policy and "appropriate" forms of nature tourism by telling visitors what to do, and what not to do...

All of these signs are designed by the park service to permanently mark territory and to do so within the general naturalized aesthetic of park service architecture and other cultural artifacts that calls for muted earth tones, indigenous materials, etc.

However, for the rest of our journey I’d like to focus on a sign that is different from the previous examples. It is a sign that you might see in a number of contexts, not just within the parks.

In a naturalistic context like a national park, road signs such as this "End Construction" sign--which might appear to be natural in a more obviously constructed context--are more problematic in the parks. For example, I now live in Austin, Texas, and teach at a university thirty miles north of my home, so I do a lot of driving. Some of the roads I drive on are currently under construction, so I see "End Construction" signs like this one every day on my way to and from school. In the context of my everyday drive through urban, suburban, and rural hinterland contexts, these signs have become naturalized for me to the point that all they mean to me is "This is where I can start driving faster again because I am out of the construction zone." When I saw this particular "End Construction" sign in a national park context a few years ago, however, the sign started to "speak" to me in different voices.

I noticed the sign as I was driving between scenic overlooks along the main scenic road in Bryce Canyon National Park. At first, I heard what I took to be its dominant message--"As you were, this is where the road construction ends." But as I started thinking about the context I was in and began to re-read the sign in my mind, I also heard both a preservationist imperative--"End Construction in the Parks Now! No more paved Scenic Roads! If you build them THEY will come!"--and a message about nature and culture--"Here is where Culture ends and Nature begins." I did not fix on these readings right away, though. I kept driving for a few minutes before I understood why I had even noticed the sign. When it hit me, I swung my truck around and returned to the sign to take a second look.

When I parked the truck at the spot where I had remembered first noticing the sign, I got out and started looking around to see if I could find a vantage point that would help me visually represent the sign's potential polyvalence in a photograph. I knew that the messages I was seeing in these forms would be invisible if I hadn't been spending a lot of time thinking about the relationship between nature and culture and about preservationist arguments about development in the parks, but I wondered if it was just something I was applying to them entirely externally as an idiosyncratic reading, or if there were elements of the space itself that had "suggested" my reading. I finally decided on the angle I am presenting here because it portrays the elements that could help me visually represent the allegorical reading I had made.

I wanted to highlight the sign, but I also wanted to show that any "reading" of the sign itself as a text was related to the surrounding context. For instance, on the right edge of the frame is a pine tree trunk with its lower limbs stripped off and a two foot-long vertical gash that starts at the ground. If you look closely at the gash, you can see that the tree is growing around it, which suggests that the tree is in the process of healing a wound. In between this tree and the "End Construction" sign is another, less fortunate tree of smaller diameter that is lying on its side with its wider end revealing a weathered saw cut. The healing gash in the one still standing made me think that the damage done to it was done by grading equipment when the road widening project first started. If that is the case then the one lying on its side may have been cut down to make way for the grader. There is also a large pothole in the road that has been patched long enough ago to already need to be repaired again itself. This shows not only that the road is old, but also that the road is being re-paved for a reason. That reason might be disrepair, but the graded swath beside the existing road suggests that the motivation for re-paving might also be to widen the road.

All of this would support an environmental reading of the scene, where the sign seems to be placed there not by an officially sanctioned National Park Service road crew but by Earth First! activists to bear witness to the damage caused by the preliminary road cut and to caution against further construction: "End Construction, NOW!" I knew that that meaning was not intended by the sign makers, but it was one that was "supported by the text and context."

However, the other message I was reading off the End Construction sign, which concerned the materialization of the spatial and rhetorical distinction between nature and culture, was more interesting to me from the beginning. It too was unintentional in a superficial sense, but it was also deeply intentional in another. As I stood in this spot looking at the sign through my viewfinder, I noticed that from this angle the road and graded roadbed cut the picture into two diagonal halves with the sign straddling the divide between them. The left signpost is right on the edge of the graded swath, but both posts still have fresh dug dirt piled up around them, which helps to visually connect the right post to the graded dirt side as well. On the right of the divide is a dense pine forest, and on the left side is first graded dirt and gravel, then the edge of the road, and then the pavement itself. The pavement is divided by a double yellow line in the middle before the other half of the road completes a mirror division going the other direction. It is not visible in this picture, but directly opposite the End Construction sign, facing the other lane of traffic, is a sign that said "Construction Ahead."

Read this way, the two road signs seem to assert that the frontier between constructed landscape and natural landscape begins at the edge of the road bed. The central boundary line is the double yellow stripe, where the pavement is deepest and the lines most literal and defined. As you move out towards the edge of the pavement, the distinctions get more ambiguous, with both the pavement and the grass making colonizing gestures into the graded earth. Taken this way, the scene seems to simultaneously support all three of the meanings I have suggested. By asserting that "This is where culture ends and where nature begins," the sign also supports the ecotourist point that the roads are spoiled by technology and commercialism and that the backcountry is free from them because it is separate from them by clear markers of difference. Traveling on the road, where the "pavement" overlays nature most deeply, it is easy to understand that you are traveling on something made by and for humans, but on either side of the road, you presumably enter into natural territory that exists as a space beyond culture, beyond representation.

Road development is a common villain for preservationists and ecotourists not only for the ecological reason that roads scar the landscape but also because roads allow more industrial tourists to come into the parks, like rain following the plow, and, as preservationist Joseph Sax argues in Mountains Without Handrails, because they offer the visitor a self-contained, "vista with a fixed beginning and end" that leaves no room for "setting one’s own agenda." For Sax, the problem with scenic overlooks and loop roads is that they do not encourage the visitor to "penetrate the park." Similarly, in Desert Solitaire, Edward Abbey argues that "real" experience of Nature as Other is only possible if we "lighten our load" and go off the beaten trail into utopian wilderness spaces free from "contamination" by urban American culture, by other tourists, and by the tourist's own "cultural baggage."

In relation to the American landscape as a whole, the parks are considered islands, but in order for preservationists and ecotourists to assert the directness of wilderness experiences in the "backcountry," they must cast the roads and concession areas as islands within the wider wilderness of the parks. And if they want to police that distinction, they know that they have to stop widening the roads in every sense, because widening the roads not only slathers layers of culture on a leveled nature, but also shrinks the area of the backcountry and blurs the distinction between on and off the beaten trail.

Seeing the points where these distinctions are most clearly represented can help us see that the binary distinction between nature and culture itself is cultural. Notice that the sign extends into the "Nature" side, and that the two trees, which are on the "Nature" side of the split, both show evidence of cultural construction/destruction. The fallen tree draws our attention further into the forest, making us wonder if the cultural construction of the wilderness might also extend further beyond in the direction it points.

As I thought about what I was seeing around the sign, I only took this one picture of the scene. But as you can tell from the description above, I was engrossed in thinking about the scene for a while. I didn't realize how much or how long until I headed back to the truck and saw that there were now seven cars parked along the road directly behind my truck or on the other side of the road. I also noticed that carloads of other tourists driving on the road were beginning to slow down to see what was going on. By the time I got back to my truck, I saw that the parked cars were opening up and groups of tourists were stretching their legs, reaching for their cameras, and coming straight for me.

My first thought was, "Shit, I recognize that guy from Fairview Point. Maybe he and his friends are mad at me for taking their pictures without asking permission. And maybe they are going to pay me back by coming over here and all taking my picture at once." In my distracted state of mind, I thought about running. But when I thought about the hundreds of pictures I had taken of tourists at National Park scenic overlooks in the previous week alone, I thought that I probably deserved such a fate, and resigned myself to it.

As they approached, I flashed a supplicant’s smile at them and tried to look friendly, but they just nodded and walked right past me towards the spot where I had been circling the "End Construction" sign. Before long, a couple in their early sixties came back to where I was now standing, leaning on the hood of my truck. The man said, "What'd you get--a bear?" When I told him I was taking a picture of the sign, he looked first at his companion and then back at me, wrinkled his brow and said, "Oh." As they turned to walk back to their car, the woman said to the man, "Takes all kinds, I guess."

Where people in urban landscapes have learned to either ignore or fear cars parked on the shoulder, most tourists in national parks have learned to read a car on the side of the road as an invitation to a communal experience of a spontaneous tourist attraction. The main reason for this is that tourists on vacation are in a heightened state of awareness of their unfamiliar surroundings. But it’s more than that. Especially in the bigger parks like Yellowstone, Olympic, Glacier, and Yosemite, where wildlife is more abundant, but also in the smaller parks like Bryce, a tourist on the side of the unmarked road taking pictures usually signifies that there is wildlife nearby. Anyone who has spent time in National Parks knows that people sometimes stop their cars in the middle of the road and hop out with a camera in tow looking for that most precious of tourist commodities: contact with the unprogrammed, the unexpected, the real.

And yet, this too, is a patterned spatial practice--one not derived directly from reading the physical signs in the park but from internalizing the ways of doing and being implicit in the process of marking difference in the parks in the first place. The larger cultural history and practice of representing and experiencing the national parks as a space outside culture--the same set of discourses that are materialized in the stone, wood, and metal signs throughout the park--did more work than a sign could ever do.

In short, my actions had marked me and the territory surrounding me as a tourist attraction, but I was a poor receptacle. When I parked on the edge of the road that day in Bryce Canyon, I was following my own equally cultured need to make sense of what I was experiencing as an academic researcher, and in the process of doing it I had attracted a crowd eager for a new way of interacting with a landscape they had already been taught that they were "competent" to understand. The tourists that joined me on the side of the road were on the road to begin with because it is the most clearly marked way to get to the tourist sites on the Official Map and Visitor Guide every visitor receives upon entering a park. However, that they departed from the road suggests that the markers that the park service establishes are never enough. Circling the sign at the edge of the road with a camera in my hand, I must have looked as if I had found what they were looking for. In the end, though, they were disappointed. Their cultural training let them down, and I did not have the time or the words to teach them a new set of spatial practices so that they could see what I was seeing.

I hope that I have done a better job here of showing that the key to understanding space as a medium is learning to see how human culture is reflected even in the most seemingly natural landscapes. Learning to see those reflections means learning to see nature as both Self and Other. It also means learning to see fellow tourists sharing the wilderness landscape as Self and Other as well. If we can learn to pay attention to the physical interpretive structures that mediate our experiences of National Park landscapes, we can begin to better understand the cultural and metaphorical interpretive structures that are brought to bear on our experiences of marked territory--teaching us that how we experience space always already structures what we experience.

|

Design, Photography, and Text © 2001 by Bob Bednar

Department of Communication

snapshot semiotics home | overview | portfolio | shadows and reflections | caught looking | deconstructing nature/culture |

|

A Visual Cultural Study of Snapshot Photography, Landscape, and Tourism in the Contemporary American West |

|