A Visual Cultural Study of Snapshot Photography, Landscape, and Tourism in the Contemporary American West

|

A Visual Cultural Study of Snapshot Photography, Landscape, and Tourism in the Contemporary American West |

|

doing cultural studies of snapshot photography

in the contemporary american west

West of Las Vegas, Nevada State Highway 160, Nevada, 25 July 1994

There is no place that is not haunted by many different spirits hidden there in silence, spirits one can "evoke" or not. Haunted Places are the only ones people can live in.

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (1984)

Like anthropologist Kathleen Stewart, I am committed to telling cultural stories that "catch themselves up in something of the force, tension, and density of cultural imaginations in practice and use," so my goal here is not only to interpret tourist snapshot semiotics, but also to evoke them in the structure of this website. It is a structure in which there is "always something more to be said"--always more strands to weave into it, always more links to make. My desire to approach the problem this way has come out of my struggle with the central methodological questions that drive my larger project on tourist semiotics: how do you approximate the relationships that make up the object under analysis--the relationships between its physical presence and its cultural resonance, and the relationships between its production and its several varieties of consumption? How do you place (or replace) the phenomenon/object into a meaningful construction of those relationships in a way that allows for analysis while still maintaining the integrity of the system of values that gives it its meaning? And how do you deal with the simultaneous resonance of it all without sounding cacophonous?

As I have searched for useful ways to map out these processes, I have found John Berger's ideas about photography and memory particularly useful. In a 1978 essay titled "Uses of Photography," Berger distinguishes between two distinct types of photographs--public photographs and private photographs. Berger says that the public photograph "usually presents an event, a seized set of appearances, which has nothing to do with us, its readers, or with the original meaning of the event. It offers information, but information severed from all lived experience." Because public photographs usually have entirely separate production and consumption contexts, they "are like images in the memory of a total stranger." On the other hand, Berger says, "The private photograph--the portrait of a mother, a picture of a daughter, a group photo of one's own team--is appreciated and read in a context which is continuous with that from which the camera removed it.." This is important because the production/consumption contexts adhere more directly to the image itself. Private images like tourist snapshots have a more visible relationship to both personal and social memory than public images do.

Berger argues that if we presented all of our images in a similar way--by consciously "placing" them within "an ongoing text of photographs"--we would be able create an effective theory and practice of "alternative photography" that builds or rebuilds radial contexts around photographs:

If we want to put a photograph back into the context of experience, social experience, social memory, we have to respect the laws of memory. . . . Memory is not unilinear at all. Memory works radially, that is to say with an enormous number of associations all leading to the same event. . . . Numerous approaches or stimuli converge upon it and lead to it. Words, comparisons, signs need to create a context for a printed photograph in a comparable way; that is to say, they must mark and leave open diverse approaches. A radial system has to be constructed around the photograph so that it may be seen in terms which are simultaneously personal, political, economic, dramatic, everyday and historic.

Using Berger's radial model to structure a story about contemporary tourist photography practices may also produce a more concrete example of the kind of "alternative photography" Berger has in mind. If what we are looking for is a way of re-integrating seemingly free-floating cultural images back into everyday life and everyday practices of perception, production, and consumption, why not turn to tourist photography as an example of how it works in the field? If we want to recover the contexts of photographic memory, we might stand to learn from how the act of photographing landscape functions for tourists as a process of personal appropriation of cultural memory.

In formulating my analysis, however, I have found that Berger's radial metaphor has one serious shortcoming. While it can account for ways that the radial "spokes" are tied to both the center "hub" and the outer "rim" and "tire" of our metaphorical wheel, it leaves little room for potential connections between the spokes themselves. Making too clear a distinction between public and private images overlooks the ways that the two talk back to each other. To account for all of these things we need to imagine something more like a web that has both radial elements and connections between them. Maybe a more pertinent metaphor than a web would be one of those kids' customized bicycle wheels decorated with ribbons that weave in and out of the spokes. This image also has the benefit of being a kind of vernacular postmodernist junk art image: like tourist photography, the wheel is a customization of an already-produced "found object"; and like tourist photography it is a patterned customization. Also like tourist photography, it functions as a display of customization that signals a membership in a particular micro-culture. Using this metaphor could allow for a discussion of both the form and the content of my evocative story: just as the child customizes the wheel by appropriating a generic object, and just as tourists appropriate public images of landscape in their own photographs, in the story that follows I appropriate general postmodernist theories of everyday practices and make them function within and between the spokes of my essay.

Let me begin my study with a textual reference to the experience of temporarily inhabiting a scenic overlook at a popular tourist attraction. I will use this reference to ground a more nuanced study of contemporary western nature tourism by using it to build a set of intertextual references to accompany the rest of the photographs I include here. If we then work outward from there, we can begin to talk more concretely about the intersections of the discourse of postmodernism and the postmodern, the discourse of American cultural studies--specifically American visual cultural studies, and the discourse of the tourist West. From there, we may start to understand the cultural work that tourists do when they try to negotiate a personal space within the visual culture of the contemporary American West, and learn to appreciate the complex layers of culturally-grounded signification embodied in something as seemingly frivolous as taking a single snapshot of the Grand Canyon.

Early in his academic satire novel White Noise (1985), Don DeLillo narrates a conversation between the main character, Jack Gladney, and Murray, Jack's academic colleague at a fictional Midwestern college. The conversation occurs at the site of "The Most Photographed Barn in America," somewhere nearby campus. As DeLillo describes it, Murray and Jack follow the signs along the road, and then the signs that lead out of the crowded parking lot and up an old cowpath to the overlook itself. Along the way they see lots of other tourists--all of whom are carrying cameras and camera equipment. Just before they get to the overlook, Jack and Murray pass a man in a booth selling postcards and color slides--pictures of the barn taken from the overlook vantage point. Instead of waiting their turn behind the overlook wall as everyone else is doing, Jack and Murray detach themselves from the crowd to stand near a grove of trees off to the side and watch as the tourist photographers wait their turn at the overlook. With words punctuated by the sounds of camera shutters and film advances, Murray says to Jack:

No one sees the barn. Once you've seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn. We're not here to capture an image, we're here to maintain one. Every photograph reinforces the aura. We see only what the others see. The thousands who were here in the past, those who will come in the future. We've agreed to be part of a collective perception. [The tourists] are taking pictures of taking pictures. . . . What was the barn like before it was photographed? What did it look like, how was it different from other barns, how was it similar to other barns? We can't answer these questions because we've read the signs, seen the people snapping the pictures. We can't get outside the aura. We're part of the aura.

Murray finds that their encounter with the barn is thoroughly mediated by signs of the barn that preclude any immediate personal experience of "the barn itself." First of all, they follow signs to their destination that itself has been designated as an "attraction." In addition to going past these literal signs, all of the visitors also must walk past the booth that sells images of the thing to be viewed and photographed (these are also "signs," just in a different sense). By walking past the booth the barn tourists literalize the general process by which we regularly consume mechanically reproduced images of culturally significant objects before we actually encounter these objects in person--if we ever encounter them at all. Note also that Jack and Murray are not alone in their quest for the barn-sign, which suggests that the photographers at the overlook had followed the same signs that they had (if not as self-consciously, nor as self-righteously) and that what Murray describes--encounters with the barn as an image of itself--is perhaps a patterned phenomenon.

If we are like Murray and this lack of access to unmediated reality is striking when we encounter a barn, just imagine how striking it can be if we see a similar phenomenon occurring at a tourist attraction that appears to be natural instead of cultural. Most of us think of nature tourism as a set of encounters with physical landscapes that form a visual field independent from us. This association between landscape and detached visual observation is not accidental; it has a long cultural history. Indeed, conceiving of landscape as a self-contained visual entity is the prerequisite for most tourism that seeks communion with natural landscape. In order to appreciate nature as nature--as the Other of culture--we must deny our own role in constructing the landscape as we encounter "it" and, as W. J. T. Mitchell argues, "erase the signs of our own constructive activity in the formation of landscape as meaning and value, . . . to imagine a representation that 'breaks through' representation into the realm of the nonhuman." To think that we are inhabiting a natural landscape and not a cultural landscape, we must ignore our own (cultural and personal) presence in the landscape and overlook these signs of culture in nature instead of looking at them.

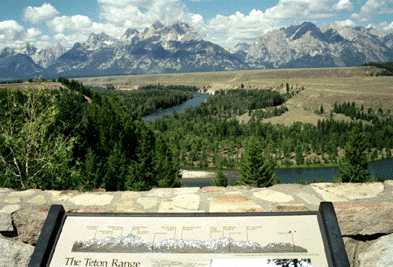

But what happens when we begin to learn to focus on these signs of culture at the same time that we focus on the landscapes mediated by them? And what happens when we as cultural studies researchers try represent the relationships between the distant vistas, the mediating structures that frame them, and the tourists who take pictures while they inhabit these structures? Can we use photographs to visually represent the processes Murray describes in White Noise? Consider the following set of four pictures I took at the Snake River Scenic Overlook in Grand Teton National Park to show the effect of replacing images of reified nature back into their cultural contexts:

|

|

|

|

However, I want to move past this overly schematic illustration of the physical frames of reference that surround the landscape and mediate any experience of it, because photographs can "tell" only part of the story "by themselves." In the gaps between these tactile mediations lurks another set of mediations--images of place from popular visual culture--that, as Michel de Certeau says, "haunt" places whether we evoke them or not. To understand how landforms are mediated by images of themselves, though, we must first understand the semiotics of landscape imagery more specifically. As Jonathan Culler writes in his 1981 essay "Semiotics of Tourism," a "semiotic perspective assists the study of tourism by preventing one from thinking of signs and sign relations as corruptions of what ought to be a direct experience of being or the natural world." In this context, the tourist's "quest for authentic experience of place" in a national park environment is then better understood as a "quest for an experience of authentic signs of place."

Like the barn tourists in DeLillo's example, when we visit scenic overlooks in the West, we always first encounter denotative signs like these that direct us to big photogenic trees, "Scenic Views," and even "Inspiration."

"Big Cedar Tree" Photospot, Olympic National Park, Washington, 5 August 1994 |

Sign for Glen Canyon Dam Overlook, Near Page, Arizona, 21 July 1994 |

"Approaching Inspiration Point," Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 11 August 1994 |

These signs certify that we are on the right track--moving towards an authentic experience of place. But in addition to these more literal signs, there are also metalinguistic signs as well. These signs mark the site within the site by separating it from surrounding objects and literally and figuratively mediating between us and the central signifier of place--the highlighted landform itself:

Smith Creek Overlook, Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, Washington, 3 August 1994 |

Glacier Point, Yosemite National Park, California, 28 July 1994 |

Overlook walls and framed viewing platforms like these are combined with official interpretive placards and visual technologies; together they act as cultural forms to signify that "this is where authentic nature tourism happens."

Inspiration Point, Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah, 22 July 1994 |

Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park, Arizona, 19 July 1994 |

But we should take this further: in addition to these physical objects acting as mediating signifiers, there are also other less visible sign systems that haunt overlooks. If landscape tourism is the search for signifiers of place, then when tourists visit a landscape that has been designated a tourist landscape, they temporarily inhabit not only a physical landscape but also a semiotic landscape. Perhaps we should say that a tourist landscape is a semiotic landscape. Marked tourist landscapes only function as tourist landscapes if they are saturated with images of themselves, thus that is part of what is inhabited by tourists when they visit, and that is part of what they reproduce in their photographs.

Jonathan Culler argues that tourists act as amateur semioticians who are "engaged in semiotic projects, reading cities, landscapes and cultures as sign systems." Sign reading is not something incidental to tourism; it is both the central way of doing it and the central reason for doing it. Places like the Grand Canyon, Yosemite Valley, and Yellowstone are not significant "in themselves"; they are significant because, like a "canonical" text that has been read and re-read countless times, they are the location of previous and present intersecting acts of signification. What makes them "resonate" as iconic landscapes is the fact that they are physical objects that function as signs of themselves.

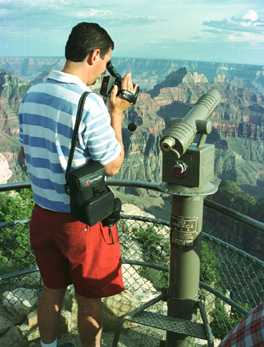

The experience national park tourists are chasing in the West is only possible in those particular landscapes because they are enriched by the sign systems that give them cultural value as multi-layered, resonant, and semiotically unique iconic landscapes. We search for the essential quality that makes each landscape "unique," like the South Rim scenic overlook views of the Colorado River and canyon stratification which give the Grand Canyon its "Grand Canyon-ness," like the faces of El Capitan and Half Dome which give Yosemite its sense of "Yosemite-ness," and like Old Faithful, which defines for many the "Yellowstone-ness" of Yellowstone. When one sees something like Old Faithful for oneself, one sees not only Old Faithful the geological phenomenon, but Old Faithful as "Old Faithful"--that is, as a semiotic phenomenon. And when one sits down on the benches provided to watch (and photograph) Old Faithful perform, to gaze into the Grand Canyon, or to make a pilgrimage to the site of Michaelangelo Antonioni's 1969 film Zabriskie Point, one inhabits an inherited subject position built from physical and metaphorical signs of previous inhabitations:

Old Faithful Viewpoint, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 11 August 1994 |

South Rim Trail, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, 20 July 1994 |

Here each of these landforms is constituted as part of a "view" that has a particular cultural history because it has been framed and re-framed over time through countless acts of representation that impinge on that physical experience and inflect its significance according to the extent and kind of intertextual references that are brought to bear (consciously and unconsciously) on the interactive encounter. Tourist landscape photography intervenes in the spaces within visual culture by quoting and inflecting previous images at the same time that it creates new ones. Tourist photographers are consumers of popular visual culture, but the second they release the shutter of their still cameras or press the record button on their video cameras, they turn an act of consumption into an act of production that establishes explicit and implicit relationships between personal acts of image-making, the general cultural semiotic storehouse, and cultural technologies of presentation. |

Bright Angel Point, North Rim, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, 21 July 1994 |

The important point here concerns the purpose of these snapshots: tourists quote inherited images to make their snapshots readable to themselves and the people they show them to as signs of "thereness." As pilgrims visiting the site of the original object, we desire the chance to make our own rendering of "already-known" signifiers. But we also quote these signifiers to help us tell our own stories.

Wawona Tunnel Overlook, Yosemite National Park, California, 28 July 1994 |

As you see in this picture of a posing ritual at Yosemite Valley, when we take pictures, we appropriate the power of the semiotic landscape by placing ourselves in the center of the resonating image, either figuratively by "taking" the picture ourselves and placing it in our personal contexts (snapshot albums or, in my case, an academic website), or literally by placing ourselves or our family and friends in front of the scene that is now literally made to function simultaneously as a background for experience, location of experience, and proof of our experience of the signs of "there-ness" of the site. We do this because quoting inherited signs of there-ness gives our photographs exchange value in our home contexts. And it is important to note that when we take these snapshots, we are not alone; instead, we are part of a communal effort to claim a personal stake in the general culture of place:

Wawona Tunnel Overlook, Yosemite National Park, California, 28 July 1994 |

Paying attention to collaboration in the process of sign reading emphasizes the "performativity" of reading as an active process that is shaped by practices on all sides of the performance. Like the notion of the passive reader-as-consumer who tries to apprehend the pre-determined, teleological, stable sign systems within a text, the notion of the tourist as a passive "consumer" of self-contained objects and images is insufficient because the notion ignores the practices that are brought to bear on a "text" in the act of reading. Much as we now understand that we can read texts and experience them as locations of the meaning we produce in our interaction with them as readers and not as collections of words to be correctly deciphered, we experience landscapes as mediating locations for the intertextual intersections that make the landscape meaningful to us as landscape "readers." This is made visible in this picture of a boy physically tracing the distant natural vista with his hand on a scale model cultural representation of the vista. His action gives a physical dimension to the act of reading and relating representations of "the text" to the represented text itself in the distance:Certainly our readings are guided by "authors" who "assume the authority" to inscribe landscapes with signs, walls, scale models, and viewing platforms that are put there "on our behalf" to make the landscapes function as legible texts, but that does not mean that we are mere passive readers of always already completed "texts," mere consumers who simply absorb scenery like thirsty sponges. Moreover, iconic western landscapes like these do not have a single "author" who has "marked" the space as an attraction. The "author" of the site is culture. And while the "text" has been previously constituted by preceding acts of signification, it is possible to encounter it (and even enjoy it) without knowing this, just as it is possible to read and enjoy a well-traveled novel without identifying the same intertextual references that a "professional reader" may discern.

|  Diablo Dam Overlook, North Cascades National Park, Washington, 6 August 1994 |

In theory, the range of possible landscape "readings" is infinite--or at least limited only by the number of possible "readers." In practice, however, the possibilities appear to be contained to a finite set of dominant conventional reading practices. Sometimes these containments are so strong that they appear to be "natural" modes of interpreting natural vistas because they are commonsensical, but they need to be thought of in terms of cultural patterns and not absolute, essential, or natural patterns of interacting with the land. To analyze the causes and effects of this "training," culturally-grounded approaches to semiotics like mine critically examine not only sign systems, but also learn from theorists of the ethnography of "everyday practice" like de Certeau and Bourdieu to pay attention to habitual "signifying practices." Like tourism itself, such an approach to cultural studies works in the spaces in between cultural artifacts and cultural meanings to show us that all connections between signifier/signified are always discursive (which opens up the possibility of change), but it also shows how cultural practices naturalize certain provisional linkages (which accounts for the structures that we must overcome or deflect when we seek such change).

The approach to the mediations between public culture and personal culture that I am outlining here has been most extensively theorized in recent cultural studies approaches to "audience ethnography." Like current ethnographic approaches to reader-response spurred by the work of Janice Radway and others, audience ethnography theories take as their starting point the premise that cultural texts are not simply transmitted to undifferentiated and passive readers/audiences but are instead the sites of active semiotic work on the part of vernacular artists formerly known as consumers. Instead of asking how consumers "receive" transmitted messages, studies in this vein ask how people actively make sense of media texts, and how the political economy of media production, the texts themselves, and consumption contexts combine to guide and restrict those acts of sense-making.

While some of the answers to these questions simply reverse the older active producers/passive audience dichotomy--transforming audiences from manipulated dupes into semiotic guerrilla warriors--the most fruitful ethnographic studies show that both sides of the relationship between producers and consumers are constrained by cultural practices. These latter studies show that we must understand the contexts and discourses that impinge on particular interpretations, including the sources of and particular deployments of power and ideology in media production contexts and audience alternations between opposition to and complicity with that power and ideology. And, as in my work on tourist snapshot practices, media research done in what John Fiske calls the "ethno-semiotic" mode focuses on the ways that particular audiences interact with already-produced media texts to construct personal identities as well as social identities within (permanent or temporary) "interpretive communities" that share not only common readings but also common interaction practices.

Before you leave, I would like to return to the question of what it means to say that landscape is a medium that can be fruitfully studied using ethnographic methods developed in media studies research and in the "new ethnography." Like literary texts and media texts such as movies, television shows, popular music, advertisements, and Internet web sites, landscapes are mediations constructed and acted upon by multiple actors in a field of dynamic interaction. But unlike these other sorts of "texts," iconic natural landscapes are singular mediations located in particular geographical places, which often obscures the fact that landscape functions as a medium for the exchange of cultural meanings. But thinking of landscape and tourism as mediations between nature, culture, and identity helps us to understand not only what tourism and landscape in the contemporary American West are, but also what they do. Here we would do well to heed the advice of W. J. T. Mitchell, who argues that in order to understand landscape, we must think of landscape as a verb instead of a noun. As Mitchell says, this entails thinking of landscape "not as an object to be seen or a text to be read, but as a process by which social and subjective identities are formed." It means asking "not just what landscape 'is' or 'means' but what it does, how it works as a cultural practice."

As I have argued here, a grounded theory of cultural semiotics can help us understand that tourist encounters with landscape are inflected not only by personal desire, but also cultural practice. Thus to understand the way that tourists "work" in the American West (or in any other area, for that matter), we must think of landscape as a cultural process in which individual tourists collaborate with other agents to produce personally and culturally meaningful representations of landscapes, and we must think of landscape as a medium of exchange for those meanings that are themselves also in a continuous state of becoming.

|

Design, Photography, and Text © 1999 by Bob Bednar

Department of Communication

snapshot semiotics home | overview | portfolio | shadows and reflections | caught looking | deconstructing nature/culture |

|

A Visual Cultural Study of Snapshot Photography, Landscape, and Tourism in the Contemporary American West |

|